Wild Hares and Hummingbirds (33 page)

Read Wild Hares and Hummingbirds Online

Authors: Stephen Moss

The pipits keep up a constant calling: a light, thin, high-pitched ‘sip’. From time to time the skylarks join in, with a burst of notes and even, occasionally, a snatch of full song. The sounds of autumn are much less varied than those of spring, but they have their own special charm, especially against the gentle lapping of waves over mud, as the tide begins to drop.

I turn for home. Thus ends my brief excursion beyond the western borders of the parish; to a place which, although utterly different in landscape and character, is umbilically connected by the River Brue to my home patch. The link between the village on the levels, and the open sea, may be well hidden, but it is still deep and true.

ALL SAINTS’ DAY

, at the beginning of November, often marks a dramatic change in the weather, as the last traces of summer finally fade, and the true character of autumn is revealed. Some years this is marked by hard frosts, but our unpredictable climate means that dank, wet weather is equally likely.

When Atlantic weather systems dominate, wave after wave of depressions sweep across that vast ocean, and funnel up the Bristol Channel, bringing more rain to an already sodden landscape. The ground soaks up the extra water for a while, but as the weeks go by the roads are awash with muddy puddles, while little pools begin to form on the fields. Day after day, the west wind whips across this flat, open land, battering the stunted trees and hedges into submission.

Just when the memory of the departed birds of summer is fading, the winter visitors start to arrive. Each night, the thin, high-pitched calls of redwings fall from the darkness like showers of autumn rain. They have come from Iceland and Scandinavia, where they breed in the low thickets of dwarf willow and birch alongside streams and bogs, or under the eaves of rural barns. I once saw a singing redwing in Iceland, and was struck by the blandness of its song; a less tuneful version of a thrush or blackbird, without the sweetness of either. But here, in their winter quarters, their only sound is this single, sibilant note.

By November redwings are here in force, thronging

the

hedgerows of the parish. As cars pass by they scatter into the air like sparks blown from a bonfire; an appropriate image, for one of their local names is ‘wind thrush’. Although they are often mistaken for starlings, there is something about their silhouette, with their blunter wings and plumper body, which marks them out as different. Only when they gather in the muddy fields to feed does their beauty reveal itself. Neater and darker than the song thrush, they show a rich, rusty-orange patch on their flanks, and a broad, creamy stripe running just above each eye.

Whenever I see redwings, their larger cousin the fieldfare is not usually far away. This is another striking and colourful bird, its deep chestnut back contrasting with a pale grey head, and creamy-yellow underparts marked with bold, black chevrons. Noticeably longer and bulkier than the redwing, this lanky thrush is another winter visitor here, crossing the North Sea from Scandinavia. As a child I recall seeing huge squadrons of fieldfares heading south-west over the flat north Norfolk landscape, uttering the harsh, chacking call which signals their annual appearance.

Fieldfares usually arrive a week or two later than redwings; perhaps their size means they can better withstand the cold, and stay put on their breeding grounds a little longer. But by mid-November they are everywhere: dotted across the fields, thronging the hedgerows, or simply proceeding high across the sky on their way further south. Those that do stay here certainly make

their

presence felt, with flocks of several hundred birds stripping a hedgerow bare, before moving on to fill their stomachs with another crop of berries.

The early arrivals also feed in the local cider-apple orchards, where loads of unpicked fruit litter the grass beneath the trees. Later in the season, if the winter stays mild, they will range across the wet fields, turning over clods of damp earth with their bills in search of worms and other invertebrate prey.

By late February many redwings and fieldfares have already started to head back north and east, and although a few linger on into early March, by the middle of the month they are gone. I miss their presence, and look forward to that night, the following autumn, when I shall hear that thin, high-pitched call of the redwing once again, in the darkened skies above the village.

O

N FIREWORK WEEKEND

we experience a suitably explosive run of weather, starting with a badly timed downpour flooding out the Bonfire Night celebrations at the White Horse Inn. The following day dawns bright and warm, but during the night there is a heavy hailstorm. Next morning, little chunks of ice are still clustered on the ground like shattered glass from a car windscreen.

I am up on the Mendips, only a few miles north of the parish, but at least 600 feet higher in altitude. We gather in

the

car park of the Swan Inn at Rowberrow, several hours before opening time: a dozen eager disciples of wild-food enthusiast Adrian Boots. We are going on a fungal foray: to learn how to forage for free food, ideally without ending up in the local casualty department.

The landscape could hardly be more different from the flat, wet vistas I am used to. We are walking through a dense woodland: little stands of oak and beech surrounded by great swathes of Norway spruce; the fast-growing, economically profitable ‘Christmas tree’ we know so well. Wildlife is both thin on the ground and hard to see among the dense, inky foliage. The only evidence that anything is here at all is the occasional snatch of sound: the trill of a wren, the peeping of goldcrests and coal tits, or the harsh screech of a distant jay. Closed, claustrophobic, this is not a place in which I feel at ease.

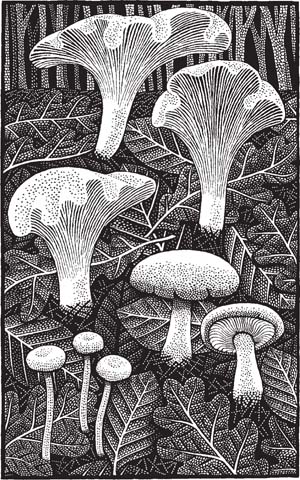

Adrian is a cheerful, personable young man, given to dispensing useful nuggets of wisdom, such as ‘the only rule of thumb about eating fungi is that there are no rules of thumb’. This is crucial advice, given the widespread belief that if a mushroom is white, grows in a field, has a flat cap or keeps a silver spoon bright when cooking, then it is safe to eat. Just one problem: several deadly poisonous mushrooms fit into one or more of these categories.

So all we can do is learn the key identification points of the edible and deadly varieties, and never trust to luck – a single moment of complacency may prove fatal. Later on, one of our party picks an innocent-looking stemmed

mushroom

with a greenish-brown cap, which Adrian identifies as a death-cap: a fungus that if we were tempted to cook and eat it, would prove fatal. Point made.

We spread out through the woods like a police forensic team, carefully scanning every inch of ground in front of us. Our task is made much more difficult by last night’s bad weather: fungi are easily damaged, and a direct hit from a hailstone can make a deep dent on their soft surface. Even when we do find a specimen, there is evidence that something else has got here first: chunks missing, or tooth-marks along the edges, suggesting that it has been nibbled by a passing slug or small mammal. All in all, the fungi are not looking their best.

Walking through a wood at such a slow, deliberate pace changes the way you appreciate the landscape. I begin to notice the patterns of the fallen beech leaves arranged in a random collage, ranging from chocolate-brown, through chestnuts, to buffs, yellows and the occasional tinge of lime-green, the summer shade retained even at this late stage of the year. The veins of the leaves overlap each other to make abstract patterns, intermingling with the greens of the surrounding brambles, ferns and moss.

Many fungi are picked, but few are chosen; and as Adrian inspects our baskets he discards most of what we have found. The temptingly named honey fungus is, he tells us, often sold in markets as an edible variety. If you do eat it, you may get a nasty stomach upset, though it won’t actually kill you. Coral fungus does indeed resemble

bright

orange corals – you wouldn’t want to eat it, even if you could.

The edible varieties bear out Adrian’s warning that appearance cannot be used as a guide to safe eating, as they could hardly be more different from one another. The common yellow brittlegill, chunky with a flat yellowish cap; the tiny amethyst deceiver, the colour of royal purple, its long, slender stalk topped with a cap the size of a penny; and several giant puffballs. These are not, alas, the huge football-sized mushrooms that can feed a family; but small, weedy specimens, whose softness to the touch indicates they have already begun to develop spores, so are no longer edible. We also find wood blewits and a beautiful orangey-yellow chanterelle, which when gently squeezed emits a delicate scent of ripe apricots.

The most peculiar specimen is Judas’s ear, which does indeed resemble a shrivelled, rubbery version of a human ear. This particular fungus has a long history: it grows on elder, and got its name from the belief that, after he betrayed Christ, Judas Iscariot hanged himself from an elder tree. This is commemorated in both the scientific name for the fungus,

Auricularia auricula-judae

, and its old vernacular name, ‘Jew’s ear’, which in these more sensitive times has understandably fallen into disuse. Another fungus rich in folklore, though not edible, is King Alfred’s cakes – so called because when you cut open these little hard lumps they look as if they are burnt inside, a feature which would have reminded our ancestors of the

famous

royal cake-burning incident that took place a few miles south of here.

Just before lunchtime, we come across what looks like a cluster of bright red apples strewn across the forest floor. These are the fly agaric, whose name comes from its traditional use as an insecticide. However, its main claim to fame is that indigenous people across Siberia have historically used it for its hallucinogenic properties, as part of their shamanic traditions.

We decide against trying to recreate this ancient practice. Instead Adrian heats up his Primus stove, chops up the few edible fungi we have managed to gather, and sautés them in a mixture of butter and olive oil. After a long morning’s walk through the woods, the smell of sizzling mushrooms is as intoxicating as any hallucinogen; and when we finally get to sample the spoils of our morning’s work, the experience is little short of culinary bliss. Each tastes subtly different from the others, with a sweet, nutty flavour far more satisfying than shop-bought mushrooms. The texture, too, is different: more squishy than firm, but not unpleasant.

As we eat, Adrian tells us about the complex relationship between trees and fungi. Tree roots are not very good at obtaining nutrition, so they use networks of underground fungi to do it for them. What we see on the surface – the fruiting bodies we call mushrooms and toadstools – are but a tiny fraction of what lies out of sight, beneath the soil. The time and effort it has taken us to collect this

meagre

offering is a salutary reminder of just how tough life was for our hunter-gatherer ancestors; and how good they must have been at knowing exactly where to look, and what to pick. Better than me, anyway.

By late afternoon the light has turned soft and even as it percolates through the trees, and the smell of the woodland begins to intensify: a not unpleasant blend of dampness and decay. As we return to the warmth of the Swan Inn for a welcome pint, a solitary raven croaks unseen overhead; reminding us of the wilderness we have shared with nature for the past few hours.