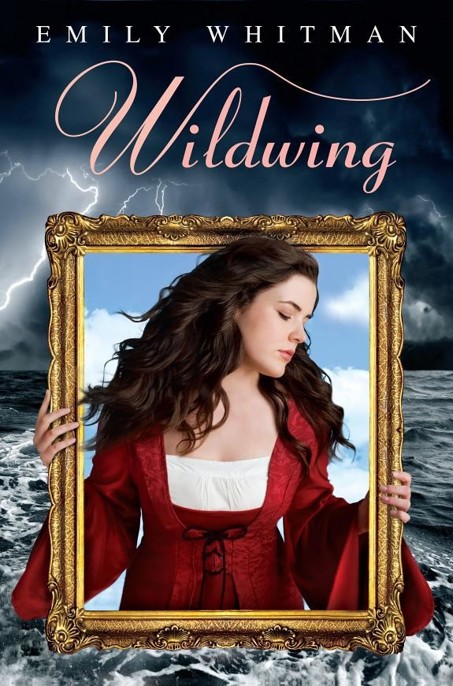

Wildwing

Authors: Emily Whitman

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Historical, #Europe, #Love & Romance

Wildwing

EMILY WHITMAN

F

or my parents,

Warren and Gerda Rovetch

Contents

Little Pembleton, September 1913 Miss High-and-Mighty

To His Most Excellent Lord, Sir Hugh of Berringstoke, From His Faithful Servant Eustace

Eustace Steps out of a Tapestry

To His Most Excellent Lord, Sir Hugh of Berringstoke, From His Faithful Servant Eustace

To His Most Excellent Lord, Sir Hugh of Berringstoke, From His Faithful Servant Eustace

To His Most Excellent Lord, Sir Hugh of Berringstoke, From His Faithful Servant Eustace

The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me, he complains of my gab and my loitering.

I too am not a bit tamed, I too am untranslatable …

—Walt Whitman

Tell all the Truth but tell it slant—Success in Circuit lies

— Emily Dickinson

Little Pembleton, September 1913

Miss

High-and-Mighty

I

t’s the same old cobbled street through the same old town, but for once I barely smell the cakes from the tea shop, don’t even pause to stare in the windows. I’m floating along, another me, in a dreamworld. Thanking God for sending a teacher so new, she hasn’t learned yet that there are somebodies and nobodies in this town, and that I’m one of the nobodies.

She’s gone and made me the queen!

I smile, remembering Caroline’s horrified gasp. She’s to be nursemaid in the play. Caroline, who tells the other girls not to talk to me, who pretends I don’t exist if we’re in the grocer’s at the same time. She turned so bright red, she looked like a furnace about to explode.

I imagine Mum’s face when she comes in the door tonight. I’ll say, “You know those costumes you stitched for the theatrical society? The ones you kept telling me not to touch? I’m to wear one even grander!”

I think of the old woman who led us down the stairs to the costume room, lit by one dim electric bulb. There were pantaloons and billowing skirts and green silk shining like the river in sunlight, and a big furry bear’s head grimacing on a shelf, and a pile of wings fluttering in a corner. The woman pulled out a gown, all red and gold and sparkling glimmer, and slipped it over my clothes.

“The length is good,” she said in a scratchy little voice. “We’ll shorten the sleeves a bit. And the neck doesn’t need to be quite so low, now does it?”

Caroline whispered something to Jane in the corner, and they burst out laughing, but I didn’t even care. I just kept looking at the yards and yards of rich fabric cascading down around me, the stones sparkling at neck and cuff.

Now, as I walk home, the street disappears, I’m so deep in imagining how I’ll walk in that gown. How I’ll hold my head. How I won’t stand aside all meek and quiet for anyone.

Suddenly a voice jabs through my thoughts like a bad cobble edge under my shoe.

“There she is,” says Caroline. “Miss High-and-Mighty.” Jane and Mary are with her; they stare at me and laugh. I put my head down low and keep walking. It’s the best day of my life; I’m not going to let them pull it to shreds.

“A queen?” Caroline sneers. “Doesn’t she look it, though!”

“In that old dress?” says Mary, smoothing her own well-tailored gabardine.

They snicker. Their bright new shoes click out the same rhythm as my mended pair. I walk faster.

Caroline’s voice gets harder, tactical, like a hunter closing in on her prey. “Queens come from good families. They know who their fathers are.”

“Right,” says Jane. “It’s all about how you’re born.”

“Who’s going to believe

her

in that role?” Caroline raises her voice so I’ll hear her over a passing motorcar. “They’ll take one look and walk out.”

“Who’s

your

father, then, Addy?” says Mary.

My feet slow as I try to repeat Mum’s words, try to think them loud enough to drown out their taunts. Don’t let them get to you again. Don’t even look in their eyes. Just disappear into yourself. It’s the only way …

“That part should have been yours, Caroline,” says Jane, the toady. “You hold yourself like a queen.”

“It’s easy for me,” says Caroline, tossing her head. “My mother isn’t a slut.”

“Look at her dress! The same she’s worn all month.”

“Ragtag queen. Secondhand queen.”

I won’t

, I think.

I won’t

. But I feel my fingers closing into a fist in my pocket.

“Can’t be a queen without a father.”

“Like mother, like daughter.”

Their voices get louder and louder, drowning out the quiet words in my head, until that familiar black anger comes surging through me, drowning out all Mum’s words, and I swing.

The door opens. Mum comes in and sees me, my needle slipping lightning fast through the rip in my skirt, neat little stitches I’d hoped to have finished before she came home, so tiny she wouldn’t notice them.

She shakes her head, sighing, and there are years of disappointment in that sigh.

“I tripped.” My words come out too fast. Even I wouldn’t believe them. “On my way home, the curb, I didn’t see it and—”

“Mrs. Miller saw you through the grocer’s window. She told me.”

I know better than to say anything. My only hope now is to look meek and obedient. I turn back to my stitching, but inside I’m praying as hard as I can,

Let her forget what she said last time. Please let her forget

.

God isn’t listening.

“So I’ve found you a place, Addy. It’s time you left school.”

Her words are a seam ripper, slashing through everything that holds me together.

“Not now!” I cry. “There’s to be a play and—” “Yes. Now.” She takes off her hat and slaps it down on the shelf, hangs her coat on the hook. “I heard Mrs. Beale is leaving to care for her sick daughter in London. She does for Mr. Greenwood. He’ll be needing someone.” “Mr. Greenwood! But he’s—”

“So he’s a little batty.” She sinks into the other chair. “There’s no harm in him. A place like this won’t come along again soon, not in this village. We couldn’t hope for better.” Here’s the thing. Mum makes her way by disappearing into the woodwork, becoming small, invisible, a mouse who tiptoes in and gratefully nibbles the crumbs that great folks leave behind. She’s always cutting out fabric, always stitching, so I can stay in school. And I work hard, I do; but I keep hearing the other girls whisper,

“Bastard bastard bastard.”

Then there’s trouble. And it’s always my fault. Mum is looking at my face. “What is it, then?” How can I tell her what it means to me, the chance to be in this play? To be someone people look up to for once, even if it’s only onstage? But to explain, I’d need to start with what they say about me—and about her. What it was like when I was young. The teasing. The names. No one to play with because, as they were only too happy to explain, their mothers warned them away from me, as if whatever taint I’d inherited were catching. What it’s still like. The raised eyebrows, the cold wind as they swerve to avoid me in the halls.

But I can’t tell Mum that. So all I say is, “Two months, until the performance, please! And then I’ll go wherever you tell me.”

She shakes her head. “He’ll have found someone else.”

“But

you’re

the one kept me in school this year, said I should stay as long as we could manage it.”

“And so I did,” she says, softer. “And so I did.”

Something flutters in my chest. One more sigh from her and I’m safe!

But then her voice turns bitter. “Now I see I was wrong. What good has it done, tell me that? Making you dream of things you can’t have. Because no matter how quick and bright you may be, you’ll still wear a maid’s apron when all is said and done. A maid in a good house if you’re lucky, a scullery slavey if you’re not. You won’t do better than this place. For God’s sake! I was ten years old when I went into service, and you a great girl of fifteen!”

She stands and walks a few steps to the side of the room that counts as our kitchen, opens the cupboard, rummages for the potatoes, an onion. “You’ve been getting above your station. Not watching your words with your betters. Let alone your fists.” She reaches for the knife and now its steady

chop, chop

underlines her anger. “It’s their money puts this roof over our heads. Puts this food on our table.”

Something rises inside me, fighting what she says, and I cry, “But I’m to be the queen!”

“The queen?” she exclaims, turning to stare at me. “That’s the problem right there! Exactly

who

do you think you are?” For a moment the knife is pointing right at my heart; when it resumes chopping, her back is to me again, a solid wall. “Why must you keep drawing attention to yourself? Holding your head up so high. Wearing your hair loose down your back, calling every eye to you—the boys stare enough as it is! It’s no wonder the others tease you.”

The acrid sting of onion fills the air. Mum wipes the crook of her elbow across her eyes. For a moment I think she’s crying, but her voice is steel as she says, “Get your head out of the clouds, Addy. This is the life you were born to.” The knife thunks down. “This is the life you have to live.”