William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition (163 page)

Read William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Online

Authors: William Shakespeare

Tags: #Drama, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare

BOOK: William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition

4.29Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

BIRON

To move wild laughter in the throat of death?—

It cannot be, it is impossible.

Mirth cannot move a soul in agony.

It cannot be, it is impossible.

Mirth cannot move a soul in agony.

ROSALINE

Why, that’s the way to choke a gibing spirit,

Whose influence is begot of that loose grace

Which shallow laughing hearers give to fools.

A jest’s prosperity lies in the ear

Of him that hears it, never in the tongue

Of him that makes it. Then if sickly ears,

Deafed with the clamours of their own dear groans,

Will hear your idle scorns, continue then,

And I will have you and that fault withal.

But if they will not, throw away that spirit,

And I shall find you empty of that fault,

Right joyful of your reformation.

Whose influence is begot of that loose grace

Which shallow laughing hearers give to fools.

A jest’s prosperity lies in the ear

Of him that hears it, never in the tongue

Of him that makes it. Then if sickly ears,

Deafed with the clamours of their own dear groans,

Will hear your idle scorns, continue then,

And I will have you and that fault withal.

But if they will not, throw away that spirit,

And I shall find you empty of that fault,

Right joyful of your reformation.

BIRON

A twelvemonth? Well, befall what will befall,

I’ll jest a twelvemonth in an hospital.

I’ll jest a twelvemonth in an hospital.

QUEEN

(to the King)

(to the King)

Ay, sweet my lord, and so I take my leave.

KING

No, madam, we will bring you on your way.

BIRON

Our wooing doth not end like an old play.

Jack hath not Jill. These ladies’ courtesy

Might well have made our sport a comedy.

Jack hath not Jill. These ladies’ courtesy

Might well have made our sport a comedy.

KING

Come, sir, it wants a twelvemonth an’ a day,

And then ’twill end.

And then ’twill end.

BIRON

That’s too long for a play.

Enter Armado the braggart

ARMADO (

to the King)

Sweet majesty, vouchsafe me.

to the King)

Sweet majesty, vouchsafe me.

QUEEN Was not that Hector?

DUMAINE The worthy knight of Troy.

ARMADO

I will kiss thy royal finger and take leave.

I am a votary, I have vowed to Jaquenetta

To hold the plough for her sweet love three year.

But, most esteemed greatness, will you hear the

dialogue that the two learned men have compiled in

praise of the owl and the cuckoo ? It should have

followed in the end of our show.

I am a votary, I have vowed to Jaquenetta

To hold the plough for her sweet love three year.

But, most esteemed greatness, will you hear the

dialogue that the two learned men have compiled in

praise of the owl and the cuckoo ? It should have

followed in the end of our show.

KING Call them forth quickly, we will do so.

ARMADO

Holla, approach!

Enter Holofernes, Nathaniel, Costard, Mote, Dull, Jaquenetta, and others

This side is Hiems, winter,

This Ver, the spring, the one maintained by the owl,

The other by the cuckoo. Ver, begin.

This Ver, the spring, the one maintained by the owl,

The other by the cuckoo. Ver, begin.

SPRING

(sings)

(sings)

When daisies pied and violets blue,

And lady-smocks, all silver-white,

And cuckoo-buds of yellow hue

Do paint the meadows with delight,

The cuckoo then on every tree

Mocks married men, for thus sings he:

Cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cuckoo—O word of fear,

Unpleasing to a married ear.

And lady-smocks, all silver-white,

And cuckoo-buds of yellow hue

Do paint the meadows with delight,

The cuckoo then on every tree

Mocks married men, for thus sings he:

Cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cuckoo—O word of fear,

Unpleasing to a married ear.

When shepherds pipe on oaten straws,

And merry larks are ploughmen’s clocks;

When turtles tread, and rooks and daws,

And maidens bleach their summer smocks,

The cuckoo then on every tree

Mocks married men, for thus sings he:

Cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cuckoo—O word of fear,

Unpleasing to a married ear.

And merry larks are ploughmen’s clocks;

When turtles tread, and rooks and daws,

And maidens bleach their summer smocks,

The cuckoo then on every tree

Mocks married men, for thus sings he:

Cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cuckoo—O word of fear,

Unpleasing to a married ear.

WINTER (sings)

When icicles hang by the wall,

And Dick the shepherd blows his nail,

And Tom bears logs into the hall,

And milk comes frozen home in pail;

When blood is nipped, and ways be foul,

Then nightly sings the staring owl:

Tu-whit, tu-whoo!—a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

And Dick the shepherd blows his nail,

And Tom bears logs into the hall,

And milk comes frozen home in pail;

When blood is nipped, and ways be foul,

Then nightly sings the staring owl:

Tu-whit, tu-whoo!—a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

When all aloud the wind doth blow,

And coughing drowns the parson’s saw,

And birds sit brooding in the snow,

And Marian’s nose looks red and raw;

When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl,

Then nightly sings the staring owl:

Tu-whit, tu-whoo!—a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

And coughing drowns the parson’s saw,

And birds sit brooding in the snow,

And Marian’s nose looks red and raw;

When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl,

Then nightly sings the staring owl:

Tu-whit, tu-whoo!—a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

⌈ARMADO⌉ The words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo. You that way, we this way.

Exeunt, severally

Exeunt, severally

ADDITIONAL PASSAGES

A. The following lines found after 4.3.293 in the First Quarto represent an unrevised version of parts of Biron’s long speech, 4.3.287-341. The first six lines form the basis of 4.3.294-9; the next three are revised at 4.3.326- 30; the next four at 4.3.300-2; the last nine are less directly related to the revised version.

And where that you have vowed to study, lords,

In that each of you have forsworn his book,

Can you still dream, and pore, and thereon look?

For when would you, my lord, or you, or you,

Have found the ground of study’s excellence

Without the beauty of a woman’s face?

From women’s eyes this doctrine I derive.

They are the ground, the books, the academes,

From whence doth spring the true Promethean fire.

Why, universal plodding poisons up

The nimble spirits in the arteries,

As motion and long-during action tires

The sinewy vigour of the traveller.

Now, for not looking on a woman’s face

You have in that forsworn the use of eyes,

And study, too, the causer of your vow.

For where is any author in the world

Teaches such beauty as a woman’s eye?

Learning is but an adjunct to ourself,

And where we are, our learning likewise is.

Then when ourselves we see in ladies’ eyes

With ourselves.

Do we not likewise see our learning there?

B. The following two lines, spoken by the Princess and found after 5.2.130 in the First Quarto, seem to represent a first draft of 5.2.131-2.

Hold, Rosaline. This favour thou shalt wear,

And then the King will court thee for his dear.

C. The following lines found after 5.2.809 in the First Quarto represent a draft version of 5.2.824-41.

BIRON

And what to me, my love? And what to me?

ROSALINE

You must be purged, too. Your sins are rank.

You are attaint with faults and perjury.

Therefore if you my favour mean to get

A twelvemonth shall you spend, and never rest

But seek the weary beds of people sick.

You are attaint with faults and perjury.

Therefore if you my favour mean to get

A twelvemonth shall you spend, and never rest

But seek the weary beds of people sick.

LOVE’S LABOUR’S WON

A BRIEF ACCOUNT

IN 1598, Francis Meres called as witnesses to Shakespeare’s excellence in comedy ‘his

Gentlemen of Verona

, his

Errors

, his

Love Labour’s Lost

, his

Love Labour’s Wone,

his

Midsummer’s Night Dream

, and his

Merchant of Venice’

. This was the only evidence that Shakespeare wrote a play called

Love’s Labour’s Won

until the discovery in 1953 of a fragment of a bookseller’s list that had been used in the binding of a volume published in 1637/8. The fragment itself appears to record titles sold from 9 to 17 August 1603 by a book dealer in the south of England. Among items headed ‘[inte]rludes & tragedyes’ are

Gentlemen of Verona

, his

Errors

, his

Love Labour’s Lost

, his

Love Labour’s Wone,

his

Midsummer’s Night Dream

, and his

Merchant of Venice’

. This was the only evidence that Shakespeare wrote a play called

Love’s Labour’s Won

until the discovery in 1953 of a fragment of a bookseller’s list that had been used in the binding of a volume published in 1637/8. The fragment itself appears to record titles sold from 9 to 17 August 1603 by a book dealer in the south of England. Among items headed ‘[inte]rludes & tragedyes’ are

marchant of vennis

taming of a shrew

knak to know a knave

knak to know an honest man

loves labor lost

loves labor won

No author is named for any of the items. All the plays named in the list except

Love’s Labour’s Won

are known to have been printed by 1600; all were written by 1596-7. Taken together, Meres’s reference in 1598 and the 1603 fragment appear to demonstrate that a play by Shakespeare called

Love’s Labour’s Won

had been performed by the time Meres wrote and was in print by August 1603. Conceivably the phrase served as an alternative title for one of Shakespeare’s other comedies, though the only one believed to have been written by 1598 but not listed by Meres is

The Taming of the Shrew,

which is named (as

The Taming of A Shrew)

in the bookseller’s fragment. Otherwise we must suppose that

Love’s Labour’s Won

is the title of a lost play by Shakespeare, that no copy of the edition mentioned in the bookseller’s list is extant, and that Heminges and Condell failed to include it in the 1623 Folio.

Love’s Labour’s Won

are known to have been printed by 1600; all were written by 1596-7. Taken together, Meres’s reference in 1598 and the 1603 fragment appear to demonstrate that a play by Shakespeare called

Love’s Labour’s Won

had been performed by the time Meres wrote and was in print by August 1603. Conceivably the phrase served as an alternative title for one of Shakespeare’s other comedies, though the only one believed to have been written by 1598 but not listed by Meres is

The Taming of the Shrew,

which is named (as

The Taming of A Shrew)

in the bookseller’s fragment. Otherwise we must suppose that

Love’s Labour’s Won

is the title of a lost play by Shakespeare, that no copy of the edition mentioned in the bookseller’s list is extant, and that Heminges and Condell failed to include it in the 1623 Folio.

None of these suppositions is implausible. We know of at least one other lost play attributed to Shakespeare (see

Cardenio,

below), and of many lost works by contemporary playwrights. No copy of the first edition of

Titus Andronicus

was known until 1904; for I Henry IV and

The Passionate Pilgrim

only a fragment of the first edition survives. And we now know that

Troilus and Cressida

was almost omitted from the 1623 Folio (probably for copyright reasons) despite its evident authenticity. It is also possible that, like most of the early editions of Shakespeare’s plays, the lost edition of

Love’s Labour’s Won

did not name him on the title-page, and this omission might go some way to explaining the failure of the edition to survive, or (if it does) to be noticed.

Love’s Labour’s Won

stands a much better chance of having survived, somewhere, than

Cardenio:

because it was printed, between 500 and 1,500 copies were once in circulation, whereas for

Cardenio

we know of only a single manuscript.

Cardenio,

below), and of many lost works by contemporary playwrights. No copy of the first edition of

Titus Andronicus

was known until 1904; for I Henry IV and

The Passionate Pilgrim

only a fragment of the first edition survives. And we now know that

Troilus and Cressida

was almost omitted from the 1623 Folio (probably for copyright reasons) despite its evident authenticity. It is also possible that, like most of the early editions of Shakespeare’s plays, the lost edition of

Love’s Labour’s Won

did not name him on the title-page, and this omission might go some way to explaining the failure of the edition to survive, or (if it does) to be noticed.

Love’s Labour’s Won

stands a much better chance of having survived, somewhere, than

Cardenio:

because it was printed, between 500 and 1,500 copies were once in circulation, whereas for

Cardenio

we know of only a single manuscript.

The evidence for the existence of the lost play (unlike that for

Cardenio)

gives us little indication of its content. Meres explicitly states, and the title implies, that it was a comedy. Its titular pairing with

Love’s Labour’s Lost

suggests that they may have been written at about the same time. Both Meres and the bookseller’s catalogue place it after

Love’s Labour’s

Lost; although neither list is necessarily chronological, Meres’s does otherwise agree with our own view of the order of composition of Shakespeare’s comedies.

Cardenio)

gives us little indication of its content. Meres explicitly states, and the title implies, that it was a comedy. Its titular pairing with

Love’s Labour’s Lost

suggests that they may have been written at about the same time. Both Meres and the bookseller’s catalogue place it after

Love’s Labour’s

Lost; although neither list is necessarily chronological, Meres’s does otherwise agree with our own view of the order of composition of Shakespeare’s comedies.

RICHARD II

THE subject matter of

Richard II

seemed inflammatorily topical to Shakespeare’s contemporaries. Richard, who had notoriously indulged his favourites, had been compelled to yield his throne to Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Hereford: like Richard, the ageing Queen Elizabeth had no obvious successor, and she too encouraged favourites—such as the Earl of Essex—who might aspire to the throne. When Shakespeare’s play first appeared in print (in 1597), and in the two succeeding editions printed during Elizabeth’s life, the episode (4.1.145-308) showing Richard yielding the crown was omitted, and in 1601, on the day before Essex led his ill-fated rebellion against Elizabeth, his fellow conspirators commissioned a special performance in the hope of arousing popular support, even though the play was said to be ‘long out of use’—surprisingly, since it was probably written no earlier than 1595.

Richard II

seemed inflammatorily topical to Shakespeare’s contemporaries. Richard, who had notoriously indulged his favourites, had been compelled to yield his throne to Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Hereford: like Richard, the ageing Queen Elizabeth had no obvious successor, and she too encouraged favourites—such as the Earl of Essex—who might aspire to the throne. When Shakespeare’s play first appeared in print (in 1597), and in the two succeeding editions printed during Elizabeth’s life, the episode (4.1.145-308) showing Richard yielding the crown was omitted, and in 1601, on the day before Essex led his ill-fated rebellion against Elizabeth, his fellow conspirators commissioned a special performance in the hope of arousing popular support, even though the play was said to be ‘long out of use’—surprisingly, since it was probably written no earlier than 1595.

But Shakespeare introduced no obvious topicality into his dramatization of Richard’s reign, for which he read widely while using Raphael Holinshed’s

Chronicles

(1577, revised and enlarged in 1587) as his main source of information. In choosing to write about Richard II (1367―1400) he was returning to the beginning of the story whose ending he had staged in

Richard III;

for Bolingbroke’s usurpation of the throne to which Richard’s hereditary right was indisputable had set in train the series of events finally expiated only in the union of the houses of York and Lancaster celebrated in the last speech of

Richard III.

Like

Richard III,

this is a tragical history, focusing on a single character; but Richard II is a far more introverted and morally ambiguous figure than Richard III. In this play, written entirely in verse, Shakespeare forgoes stylistic variety in favour of an intense, plangent lyricism.

Chronicles

(1577, revised and enlarged in 1587) as his main source of information. In choosing to write about Richard II (1367―1400) he was returning to the beginning of the story whose ending he had staged in

Richard III;

for Bolingbroke’s usurpation of the throne to which Richard’s hereditary right was indisputable had set in train the series of events finally expiated only in the union of the houses of York and Lancaster celebrated in the last speech of

Richard III.

Like

Richard III,

this is a tragical history, focusing on a single character; but Richard II is a far more introverted and morally ambiguous figure than Richard III. In this play, written entirely in verse, Shakespeare forgoes stylistic variety in favour of an intense, plangent lyricism.

Our early impressions of Richard are unsympathetic. Having banished Mowbray and Bolingbroke, he behaves callously to Bolingbroke’s father, John of Gaunt, a stern upholder of the old order to whose warning against his irresponsible behaviour he pays no attention, and upon Gaunt’s death confiscates his property with no regard for Bolingbroke’s rights. During Richard’s absence on an Irish campaign, Bolingbroke returns to England and gains support in his efforts to claim his inheritance. Gradually, as the balance of power shifts, Richard makes deeper claims on the audience’s sympathy. When he confronts Bolingbroke at Flint Castle (3.1) he eloquently laments his imminent deposition even though Bolingbroke insists that he comes only to claim what is his; soon afterwards (4.1.98-103) the Duke of York announces Richard’s abdication. The transference of power is effected in a scene of lyrical expansiveness, and Richard becomes a pitiable figure as he is led to imprisonment in Pomfret (Pontefract) Castle while his former queen is banished to France. Richard’s self-exploration reaches its climax in his soliloquy spoken shortly before his murder at the hands of Piers Exton; at the end of the play, Henry, anxious and guilt-laden, denies responsibility for the murder and plans an expiatory pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

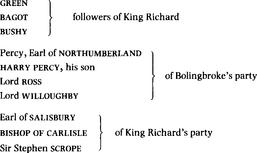

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAYKING RICHARD II

The QUEEN, his wife

JOHN OF GAUNT, Duke of Lancaster, Richard’s uncle

Harry BOLINGBROKE, Duke of Hereford, John of Gaunt’s son, later

KING HENRY IV

DUCHESS OF GLOUCESTER, widow of Gaunt’s and York’s brother

Duke of YORK, King Richard’s uncle

DUCHESS OF YORK

Duke of AUMERLE, their son

Thomas MOWBRAY, Duke of NorfolkLord BERKELEY

Lord FITZWALTER

Duke of SURREY

ABBOT OF WESTMINSTER

Sir Piers EXTON

LORD MARSHAL

HERALDS

CAPTAIN of the Welsh army

LADIES attending the Queen

GARDENER

Gardener’s MEN

Exton’s MEN

KEEPER of the prison at Pomfret

GROOM of King Richard’s stable,

Lords, soldiers, attendants

Other books

The Twelve Dancing Princesses (Faerie Tale Collection) by James, Jenni

Lady Danger (The Warrior Maids of Rivenloch, Book 1) by Campbell, Glynnis, McKerrigan, Sarah

Revenge: An Alpha Billionaire Romance by Lauren Landish

Vacation to Die For by Josie Brown

Living the Dream by Annie Dalton

Crackhead II: A Novel by Lennox, Lisa

Too Dangerous to Desire by Cara Elliott

The Private Club by J. S. Cooper

You Are a Writer by Jeff Goins, Sarah Mae