William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition (511 page)

Read William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Online

Authors: William Shakespeare

Tags: #Drama, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare

BOOK: William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition

8.28Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

SECOND LORD

Peace, ho! No outrage, peace.

The man is noble, and his fame folds in

This orb o’th’ earth. His last offences to us

Shall have judicious hearing. Stand, Aufidius,

And trouble not the peace.

This orb o’th’ earth. His last offences to us

Shall have judicious hearing. Stand, Aufidius,

And trouble not the peace.

CORIOLANUS ⌈

drawing his sword

⌉

drawing his sword

⌉

O that I had him with six Aufidiuses,

Or more, his tribe, to use my lawful sword!

Or more, his tribe, to use my lawful sword!

AUFIDIUS ⌈

drawing his sword

⌉

drawing his sword

⌉

Insolent villain!

ALL THE CONSPIRATORS Kill, kill, kill, kill, kill him!

Two Conspirators draw and kill Martius, who falls. Aufidius

⌈

and Conspirators

⌉

stand on him

LORDS

Hold, hold, hold, hold!

AUFIDIUS

My noble masters, hear me speak.

FIRST LORD

O Tullus!

SECOND LORD (

to Aufidius

)

to Aufidius

)

Thou hast done a deed whereat

Valour will weep.

THIRD LORD ⌈

to Aufidius and the Conspirators

⌉

to Aufidius and the Conspirators

⌉

Tread not upon him, masters.

All be quiet. Put up your swords.

AUFIDIUS My lords,

When you shall know—as in this rage

Provoked by him you cannot—the great danger

Which this man’s life did owe you, you’ll rejoice

That he is thus cut off. Please it your honours

To call me to your senate, I’ll deliver

Myself your loyal servant, or endure

Your heaviest censure.

Provoked by him you cannot—the great danger

Which this man’s life did owe you, you’ll rejoice

That he is thus cut off. Please it your honours

To call me to your senate, I’ll deliver

Myself your loyal servant, or endure

Your heaviest censure.

FIRST LORD Bear from hence his body,

And mourn you for him. Let him be regarded

As the most noble corpse that ever herald

Did follow to his urn.

As the most noble corpse that ever herald

Did follow to his urn.

SECOND LORD His own impatience

Takes from Aufidius a great part of blame.

Let’s make the best of it.

Let’s make the best of it.

AUFIDIUS

My rage is gone,

And I am struck with sorrow. Take him up.

Help three o’th’ chiefest soldiers; I’ll be one.

Beat thou the drum, that it speak mournfully.

Trail your steel pikes. Though in this city he

Hath widowed and unchilded many a one,

Which to this hour bewail the injury,

Yet he shall have a noble memory. Assist.

Help three o’th’ chiefest soldiers; I’ll be one.

Beat thou the drum, that it speak mournfully.

Trail your steel pikes. Though in this city he

Hath widowed and unchilded many a one,

Which to this hour bewail the injury,

Yet he shall have a noble memory. Assist.

A dead march sounded. Exeunt

bearing the body of Martius

bearing the body of Martius

THE WINTER’S TALE

THE astrologer Simon Forman saw

The Winter’s Tale

at the Globe on 15 May 1611. Just how much earlier the play was written is not certainly known. During the sheep-shearing feast in Act 4, twelve countrymen perform a satyrs’ dance that three of them are said to have already ‘danced before the King’. This is not necessarily a topical reference, but satyrs danced in Ben Jonson’s

Masque of Oberon

, performed before King James on 1 January 1611. It seems likely that this dance was incorporated in

The Winter’s Tale

(just as, later, another masque dance seems to have been transferred to

The Two Noble Kinsmen

). But it occurs in a self-contained passage that may well have been added after Shakespeare wrote the play itself.

The Winter’s Tale

, first printed in the 1623 Folio, is usually thought to have been written after

Cymbeline

, but stylistic evidence places it before that play, perhaps in 1609-10.

The Winter’s Tale

at the Globe on 15 May 1611. Just how much earlier the play was written is not certainly known. During the sheep-shearing feast in Act 4, twelve countrymen perform a satyrs’ dance that three of them are said to have already ‘danced before the King’. This is not necessarily a topical reference, but satyrs danced in Ben Jonson’s

Masque of Oberon

, performed before King James on 1 January 1611. It seems likely that this dance was incorporated in

The Winter’s Tale

(just as, later, another masque dance seems to have been transferred to

The Two Noble Kinsmen

). But it occurs in a self-contained passage that may well have been added after Shakespeare wrote the play itself.

The Winter’s Tale

, first printed in the 1623 Folio, is usually thought to have been written after

Cymbeline

, but stylistic evidence places it before that play, perhaps in 1609-10.

A mid sixteenth-century book classes ‘winter tales’ along with ‘old wives’ tales‘; Shakespeare’s title prepared his audiences for a tale of romantic improbability, one to be wondered at rather than believed; and within the play itself characters compare its events to ‘an old tale’ (5.2.61; 5.3.118). The comparison is just: Shakespeare is dramatizing a story by his old rival Robert Greene, published as

Pandosto: The Triumph of Time

in or before 1588. This gave Shakespeare his plot outline, of a king (Leontes) who believes his wife (Hermione) to have committed adultery with another king (Polixenes), his boyhood friend, and who casts off his new-born daughter (Perdita—the lost one) in the belief that she is his friend’s bastard. In both versions the baby is brought up as a shepherdess, falls in love with her supposed father’s son (Florizel in the play), and returns to her real father’s court where she is at last recognized as his daughter. In both versions, too, the wife’s innocence is demonstrated by the pronouncement of the Delphic oracle, and her husband passes the period of his daughter’s absence in penitence; but Shakespeare alters the ending of his source story, bringing it into line with the conventions of romance. He adopts Greene’s tripartite structure, but greatly develops it, adding for instance Leontes’ steward Antigonus and his redoubtable wife Paulina, along with the comic rogue Autolycus, ‘snapper-up of unconsidered trifles’.

Pandosto: The Triumph of Time

in or before 1588. This gave Shakespeare his plot outline, of a king (Leontes) who believes his wife (Hermione) to have committed adultery with another king (Polixenes), his boyhood friend, and who casts off his new-born daughter (Perdita—the lost one) in the belief that she is his friend’s bastard. In both versions the baby is brought up as a shepherdess, falls in love with her supposed father’s son (Florizel in the play), and returns to her real father’s court where she is at last recognized as his daughter. In both versions, too, the wife’s innocence is demonstrated by the pronouncement of the Delphic oracle, and her husband passes the period of his daughter’s absence in penitence; but Shakespeare alters the ending of his source story, bringing it into line with the conventions of romance. He adopts Greene’s tripartite structure, but greatly develops it, adding for instance Leontes’ steward Antigonus and his redoubtable wife Paulina, along with the comic rogue Autolycus, ‘snapper-up of unconsidered trifles’.

The intensity of poetic suffering with which Leontes expresses his irrational jealousy is matched by the lyrical rapture of the love episodes between Florizel and Perdita. In both verse and prose

The Winter’s Tale

shows Shakespeare’s verbal powers at their greatest, and his theatrical mastery is apparent in, for example, Hermione’s trial (3.1) and the daring final scene in which time brings about its triumph.

The Winter’s Tale

shows Shakespeare’s verbal powers at their greatest, and his theatrical mastery is apparent in, for example, Hermione’s trial (3.1) and the daring final scene in which time brings about its triumph.

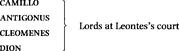

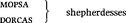

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAYLEONTES, King of SicilyHERMIONE, his wifeMAMILLIUS, his sonPERDITA, his daughterPAULINA, Antigonus’s wifeEMILIA, a lady attending on HermioneA JAILERA MARINEROther Lords and Gentlemen, Ladies, Officers, and Servants at Leontes’s courtPOLIXENES, King of BohemiaFLORIZEL, his son, in love with Perdita; known as DoriclesARCHIDAMUS, a Bohemian lordAUTOLYCUS, a rogue, once in the service of FlorizelOLD SHEPHERDCLOWN, his sonSERVANT of the Old ShepherdOther Shepherds and ShepherdessesTwelve countrymen disguised as satyrsTIME, as chorus

Enter Camillo and Archidamus

ARCHIDAMUS If you shall chance, Camillo, to visit Bohemia on the like occasion whereon my services are now on foot, you shall see, as I have said, great difference betwixt our Bohemia and your Sicilia.

CAMILLO I think this coming summer the King of Sicilia means to pay Bohemia the visitation which he justly owes him.

ARCHIDAMUS Wherein our entertainment shall shame us, we will be justified in our loves; for indeed—

CAMILLO Beseech you—

ARCHIDAMUS Verily, I speak it in the freedom of my knowledge. We cannot with such magnificence—in so rare—I know not what to say.—We will give you sleepy drinks, that your senses, unintelligent of our insufficience, may, though they cannot praise us, as little accuse us.

CAMILLO You pay a great deal too dear for what’s given freely.

ARCHIDAMUS Believe me, I speak as my understanding instructs me, and as mine honesty puts it to utterance.

CAMILLO Sicilia cannot show himself over-kind to Bohemia. They were trained together in their childhoods, and there rooted betwixt them then such an affection which cannot choose but branch now. Since their more mature dignities and royal necessities made separation of their society, their encounters—though not personal—hath been royally attorneyed with interchange of gifts, letters, loving embassies, that they have seemed to be together, though absent; shook hands as over a vast; and embraced as it were from the ends of opposed winds. The heavens continue their loves.

ARCHIDAMUS I think there is not in the world either malice or matter to alter it. You have an unspeakable comfort of your young prince, Mamillius. It is a gentleman of the greatest promise that ever came into my note.

CAMILLO I very well agree with you in the hopes of him. It is a gallant child; one that, indeed, physics the subject, makes old hearts fresh. They that went on crutches ere he was born desire yet their life to see him a man.

ARCHIDAMUS Would they else be content to die?

CAMILLO Yes—if there were no other excuse why they should desire to live.

ARCHIDAMUS If the King had no son they would desire to live on crutches till he had one. Exeunt

1.2Enter Leontes, Hermione, Mamillius, Polixenes,

and ⌈

Camillo

⌉

POLIXENES

Nine changes of the wat‘ry star hath been

The shepherd’s note since we have left our throne

Without a burden. Time as long again

Would be filled up, my brother, with our thanks,

And yet we should for perpetuity

Go hence in debt. And therefore, like a cipher,

Yet standing in rich place, I multiply

With one ‘We thank you’ many thousands more

That go before it.

The shepherd’s note since we have left our throne

Without a burden. Time as long again

Would be filled up, my brother, with our thanks,

And yet we should for perpetuity

Go hence in debt. And therefore, like a cipher,

Yet standing in rich place, I multiply

With one ‘We thank you’ many thousands more

That go before it.

LEONTES

Stay your thanks a while,

And pay them when you part.

POLIXENES

Sir, that’s tomorrow. I am questioned by my fears of what may chance

Or breed upon our absence, that may blow

No sneaping winds at home to make us say

‘This is put forth too truly.’ Besides, I have stayed

To tire your royalty.

Or breed upon our absence, that may blow

No sneaping winds at home to make us say

‘This is put forth too truly.’ Besides, I have stayed

To tire your royalty.

LEONTES

We are tougher, brother,

Than you can put us to’t.

POLIXENES

No longer stay.

LEONTES

One sennight longer.

POLIXENES

Very sooth, tomorrow.

LEONTES

We’ll part the time between’s, then; and in that

I’ll no gainsaying.

I’ll no gainsaying.

POLIXENES

Press me not, beseech you, so.

There is no tongue that moves, none, none i‘th’ world

So soon as yours, could win me. So it should now,

Were there necessity in your request, although

’Twere needful I denied it. My affairs

Do even drag me homeward; which to hinder

Were, in your love, a whip to me; my stay

To you a charge and trouble. To save both,

Farewell, our brother.

So soon as yours, could win me. So it should now,

Were there necessity in your request, although

’Twere needful I denied it. My affairs

Do even drag me homeward; which to hinder

Were, in your love, a whip to me; my stay

To you a charge and trouble. To save both,

Farewell, our brother.

LEONTES

Tongue-tied, our queen? Speak you.

HERMIONE

I had thought, sir, to have held my peace until

You had drawn oaths from him not to stay. You, sir,

Charge him too coldly. Tell him you are sure

All in Bohemia’s well. This satisfaction

The bygone day proclaimed. Say this to him,

He’s beat from his best ward.

You had drawn oaths from him not to stay. You, sir,

Charge him too coldly. Tell him you are sure

All in Bohemia’s well. This satisfaction

The bygone day proclaimed. Say this to him,

He’s beat from his best ward.

LEONTES

Well said, Hermione!

HERMIONE

To tell he longs to see his son were strong.

But let him say so then, and let him go.

But let him swear so and he shall not stay,

We’ll thwack him hence with distaffs.

(To Polixenes) Yet of your royal presence I’ll adventure

The borrow of a week. When at Bohemia

You take my lord, I’ll give him my commission

To let him there a month behind the gest

Prefixed for’s parting.—Yet, good deed, Leontes,

I love thee not a jar o’th’ clock behind

What lady she her lord.—You’ll stay?

But let him say so then, and let him go.

But let him swear so and he shall not stay,

We’ll thwack him hence with distaffs.

(To Polixenes) Yet of your royal presence I’ll adventure

The borrow of a week. When at Bohemia

You take my lord, I’ll give him my commission

To let him there a month behind the gest

Prefixed for’s parting.—Yet, good deed, Leontes,

I love thee not a jar o’th’ clock behind

What lady she her lord.—You’ll stay?

Other books

The Great Galloon and the Pirate Queen by Tom Banks

Unti Lucy Black Novel #3 by Brian McGilloway

Conflicted (Undercover #2) by Helena Newbury

Fool on the Hill by Matt Ruff

The History of England - Vols. 1 to 6 by David Hume

The Doctor Claims His Bride by Fiona Lowe

Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography by Charles Moore

Man of Wax by Robert Swartwood

Seconds by Sylvia Taekema

Friendship Dance by Titania Woods