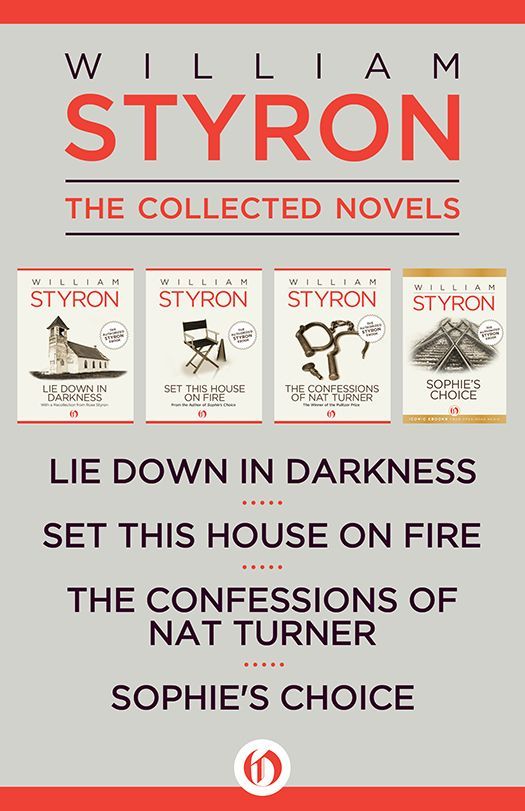

William Styron: The Collected Novels: Lie Down in Darkness, Set This House on Fire, The Confessions of Nat Turner, and Sophie's Choice

Authors: William Styron

William Styron

AFTERWORD:

Nat Turner Revisited

William Styron

For

SIGRID

Recollection

I

MET

B

ILL

S

TYRON

soon after he had published

Lie Down in Darkness.

I was a student at Johns Hopkins, and a professor, Louis Rubin, alerted us he was bringing the bestselling novelist as a speaker. Bill Styron was tall, pale, handsome, shy, nervous, not very impressive. We poets and critics left without personal conversation, or his book.

Fast forward. Bill won the Rome Prize, a year at the American Academy there, the first novelist to be awarded that august grant. He went for some months first to Paris, helped found

The Paris Review

, and arrived in Rome about the same time I did—the autumn of 1952. I had a master’s degree, a book offer, and a chance to live and write in my favorite city. Soon after settling in, I received a letter from Louis Rubin, saying, “You remember Bill Styron—he’s in Rome, too. If you’re ever at the AA, look him up. He doesn’t have friends in Italy yet.”

As chance would have it, I had a date that very week with a classicist who was also a fellow at the Academy. The beautiful Stanford White edifice, surrounded by gardens atop the Janiculum Hill enchanted me. My date did not. On the way out I passed the wall of cubbyholes where the fellows received mail, and on a fanciful whim, dropped a note into Bill Styron’s box.

Next afternoon, in my new room across town, I got a call from the writer—asking if I could come for a drink tomorrow at the Excelsior Hotel, in its little bar down the steps from the lobby? I could.

I made a dramatic entrance (Bill said), descending the steps to the bar in a black rain cape with a scarlet lining. I discovered Bill sitting between a young man I was introduced to as an artist from the Academy, and another young man—the celebrated author Truman Capote. Bill and Truman were both Southerners, only a few months apart in age, and Bill was a great admirer of Truman’s writing. They had met for the first time only a few moments earlier. Truman was living and writing in Rome on the Via Margutta, where a number of artists had apartments. Visually they were a study in contrasts. Bill was tall, with fine features, pretty sexy-looking in a checked sports shirt, khakis, and an old pair of canvas espadrilles with holes worn through them. Truman was in a sailor suit, complete with a silver bosun’s whistle. An instant three-way friendship ensued.

Bill confessed a fear of heights. He told us that earlier in the afternoon he and Wanda Malinowski, a former girlfriend from New York who happened to be in Rome, had climbed the stairs that wound up to a balcony high inside the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican. At the top he was seized by fright. His legs shook under the table as he described the agonizing climb back down.

I found myself liking him a lot. At the end of the evening, Truman said, “Hey Bill, you ought to marry this girl.”

I loved Truman’s writing, but I had not yet read Bill’s. Truman said

Lie Down in Darkness

was a terrific book, and I lied and said, “Yes, terrific book.” The next day I thought I’d better read it, because he’d already called to ask to see me again. I went around to every street in Rome that carried English-language books. In vain. Finally, I went to the American library just before closing time and asked for it. The librarian looked, smiled, and handed me a volume in an opaque dust jacket, the routine one for books in American libraries abroad. The opening announced

Lie Down in Darkness.

That night I sat up in bed reading, and after a couple of chapters I thought, “Oh, dear. He’s cute but he can’t write. What am I going to do?” The next morning I opened the book to the title page and discovered that it wasn’t Bill Styron’s

Lie Down in Darkness

at all. It was a book by Hoffman Reynolds Hays, with the same title, that had been published some time earlier. I breathed a huge sigh of relief. When I saw Bill that evening, abashed I confessed. He laughed, thought it was funny, and gave me a copy of his book, which I happily read the next day and night, relieved and awed to realize it was brilliant.

A swift romance bloomed.

—Rose Styron

April, 2010

AND since death must be the

Lucina

of life, and even Pagans could doubt, whether thus to live were to die; since our longest sun sets at right descencions, and makes but winter arches, and therefore it cannot be long before we lie down in darkness, and have our light in ashes; since the brother of death daily haunts us with dying mementos, and time that grows old in itself, bids us hope no long duration;—diuturnity is a dream and folly of expectation.

—SIR THOMAS BROWNE

Urn Burial

Carry me along, taddy, like you

done through the toy fair.

—FINNEGANS WAKE

R

IDING DOWN TO

Port Warwick from Richmond, the train begins to pick up speed on the outskirts of the city, past the tobacco factories with their ever-present haze of acrid, sweetish dust and past the rows of uniformly brown clapboard houses which stretch down the hilly streets for miles, it seems, the hundreds of rooftops all reflecting the pale light of dawn; past the suburban roads still sluggish and sleepy with early morning traffic, and rattling swiftly now over the bridge which separates the last two hills where in the valley below you can see the James River winding beneath its acid-green crust of scum out beside the chemical plants and more rows of clapboard houses and into the woods beyond.

Suddenly the train is burrowing through the pinewoods, and the conductor, who looks middle-aged and respectable like someone’s favorite uncle, lurches through the car asking for tickets. If you are particularly alert at that unconscionable hour you notice his voice, which is somewhat guttural and negroid—oddly fatuous-sounding after the accents of Columbus or Detroit or wherever you came from—and when you ask him how far it is to Port Warwick and he says, “Ab

oot

eighty miles,” you know for sure that you’re in the Tidewater. Then you settle back in your seat, your face feeling unwashed and swollen from the intermittent sleep you got sitting up the night before and your gums sore from too many cigarettes, and you try to doze off, but the nap of the blue felt seat prickles your neck and so you sit up once more and cross your legs, gazing drowsily at the novelty salesman from Allentown P-a, next to you, who told you last night about his hobby, model trains, and the joke about the two college girls at the Hotel Astor, and whose sleek face, sprouting a faint gray crop of stubble, one day old, is now peacefully relaxed, immobile in sleep, his breath issuing from slightly parted lips in delicate sighs. Or, turning away, you look out at the pinewoods sweeping past at sixty miles an hour, the trees standing close together green and somnolent, and the brown-needled carpet of the forest floor dappled brightly in the early morning light, until the white fog of smoke from the engine ahead swirls and dips against the window like a tattered scarf and obscures the view.

Now the sun is up and you can see the mist lifting off the fields and in the middle of the fields the solitary cabins with their slim threads of smoke unwinding out of plastered chimneys and the faint glint of fire through an open door and, at a crossing, the sudden, swift tableau of a Negro and his hay-wagon and a lop-eared mule: the Negro with his mouth agape, exposing pink gums, staring at the speeding train until the smoke obscures him, too, from view, and the one dark-brown hand held cataleptic in the air.

Stirring, the novelty salesman looks drowsily out of the window and grunts, “Where are we?” and you murmur, “Not far from Port Warwick, I hope,” and as he turns on his side to sleep some more you finger your copy of the

Times-Dispatch

which the newsboy sold you an hour ago, and which you haven’t read and won’t read because maybe you have things on your mind; and instead you look out once more at the late summer landscape and the low, sorrowful beauty of tideland streams winding through marshes full of small, darting, frightened noises and glistening and dead silent at noon, except for a whistle, far off, and a distant rumble on the rails. And most likely, as the train streaks past the little log-road stations with names like Apex and Jewel, a couple of Negroes are working way out in the woods sawing timber, and they hear the whistle of your train and one of them stands erect from his end of the saw, wiping away the beads of sweat gathered on his brow like tiny blisters, and says, “Man, dat choo-choo’s goin’ to Richmond,” and the other says, “Naw, she goin’ to Po’t Wa’ick,” and the other says happily, “Hoo-ee, dat’s a poontang town, sho enough,” and they laugh together as the saw resumes its hot metallic rip and the sun burns down in the swarming, resonant silence.