Winning the Wallflower: A Novella (19 page)

Read Winning the Wallflower: A Novella Online

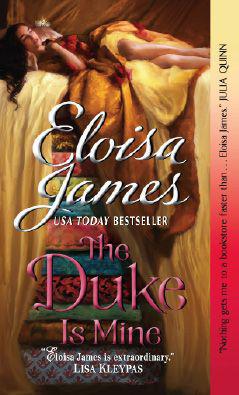

Authors: Eloisa James

After a minute or so, Linnet ventured to say, “A prince, Aunt Zenobia?”

That gained her the beatific smile of an actress receiving accolades, if not armfuls of roses, from her audience. “A prince, my dear. And you, lucky girl, have exactly what he needs. He’s looking for a heir, and you have that heir, and what’s more, you’re offering royal bloodlines.”

“I see what you mean,” the viscount said slowly. “It’s not a terrible idea, Zenobia.”

She got a little pink in the face. “None of my ideas are terrible. Ever.”

“But I don’t have a prince,” Linnet said. “If I understand you correctly, the Duke of Windebank is looking for a pregnant woman—”

Her father growled and she amended her statement. “That is, the duke would perhaps acquiesce to a woman in my unfortunate situation because that way his son would have a son—”

“Not just a son,” Zenobia said, her voice still triumphant. “A prince. Windebank isn’t going to take just any lightskirt into his family. He’s frightfully haughty, you know. He’d rather die. But a prince’s son? He’ll fall for that.”

“But—”

“You’re right about that, Zenobia. Be gad, you’re a canny old woman!” her father roared.

Zenobia’s back snapped straight. “What did you say to me, Cornelius?”

He waved his hand. “Didn’t mean it that way, didn’t mean it that way. Pure admiration. Pure unmitigated admiration. Pure—”

“I agree,” she said in a conciliatory tone, patting her hair. “It’s a perfect plan. You’d better go to him this afternoon, though. You have to get her all the way to Wales for the marriage. Marchant lives up there.”

“Marriage,” Linnet said. “Aren’t you forgetting something?”

They both looked at her and said simultaneously, “What?”

“I’m not carrying a prince!” she shouted. “I never slept with Augustus. Inside my belly I have nothing but a chewed-up crumpet.”

“That is a disgusting comment,” her aunt said with a shudder.

“I agree,” her father chimed in. “Quite distasteful. You sound like a city wife, talking of food in that manner.”

“Distasteful is the fact that you are planning to sell off my unborn child to a duke with a penchant for royalty—when I don’t even have an unborn child!”

“I said this would all have to happen quite quickly,” her aunt said.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, let’s say that your father goes to Windebank’s house this very afternoon, and let’s say that Windebank takes the bait, because he will. As I said, the man is desperate, and besides, he would love to meld his line with royal blood.”

“That doesn’t solve the problem,” Linnet said.

“Well, of course not,” Zenobia said, giving her a kindly smile. “We can’t do everything for you. The next part is up to you.”

“What do you mean?”

Her father got up, obviously not listening. “I’ll put on my Jean de Bry coat and Hessians,” he said to himself.

“Not

the de Bry,” Zenobia called after him.

He paused at the door. “Why not?”

“The shoulders are a trifle anxious. You mustn’t seem anxious. You’re offering to save the man’s line, after all.”

“Sage-green court coat with a scalloped edge,” her father said, nodding, and disappeared through the door.

“Aunt Zenobia,” Linnet said, showing infinite patience, to her mind. “Just how am I supposed to get a child of royal blood to offer to the husband I’ve never met?”

Zenobia smiled. “My dear, you aren’t a woman of my family if you have to ask

that

.”

Linnet’s mouth fell open. “You don’t mean—”

“Of course, darling. As soon as your father signs those papers, you have . . . oh . . . twelve hours before you really should leave for Wales.”

“Twelve hours,” Linnet echoed, hoping she was mistaken in what she was thinking. “You can’t possibly mean—”

“Augustus has been following you about like a child with a string toy,” her aunt said. “Shouldn’t take more than a come-hither glance and a cheerful smile. Goodness’ sake, dear, didn’t you learn anything from your mother?”

“No,” Linnet said flatly.

“Actually, with your bosom you don’t even need to smile,” Zenobia said.

“So you really mean—” Linnet stopped. “I—I—”

“You. Augustus. Seduction. Bed,” her aunt said helpfully. “Twelve hours and only one prince . . . should be quite easy.”

“I—”

“You

are

Rosalyn’s daughter,” her aunt said. “And my niece. Seduction, especially when it comes to royalty, is bred in your bones. In your very bloodline.”

“I don’t know how,” Linnet said flatly. “I may look naughty, but I’m not.”

“Yes, you are,” her aunt said brightly. She rose. “Just get yourself a child, Linnet. Think how many young women manage to do it and they haven’t nearly your advantages, to wit, your body, your face, your smile.”

“My entire education has been directed at chastity,” Linnet pointed out. “I had a governess a good five years longer than other girls, just so I wouldn’t learn such things.”

“Your father’s fault. He was frightened by Rosalyn’s indiscretions.”

There must have been something about Linnet’s face, because Zenobia sighed with the air of a woman supporting the weight of the world. “I suppose I could find you a willing man if you really can’t bring yourself to approach the prince. It’s most unconventional, but of course one knows, one cannot help but know, of establishments that might help.”

“What sort of establishments?”

“Brothels catering to women, of course,” Zenobia said. “I do believe there’s one near Covent Garden that I was just told about . . . men of substance, that’s what I heard. They come for the sport of it, I suppose.”

“Aunt, you can’t possibly mean—”

“If you can’t seduce the prince, we’ll have to approach the problem from another angle,” she said, coming over and patting Linnet’s arm. “I’ll take you to the brothel. As I understand it, a lady can stand behind a curtain and pick out the man she wants. We’d better choose one with a resemblance to Augustus. I wonder if we could just send a message to that effect and have the man delivered in a carriage?”

Linnet groaned.

“I don’t want you to think that I would ever desert you in your hour of need,” her aunt said. “I feel all the burden of a mother’s love, now that darling Rosalyn is gone.”

It was amazing how her aunt had managed to ignore that burden during the season and indeed for years before that, but Linnet couldn’t bring herself to point it out. “I am not going to a brothel,” she stated.

“In that case,” Zenobia said cheerily, “I suggest you sit down and write that naughty prince a little note. You’re wise to choose him over the brothel, truly. One hates to start marriage with a fib involving babies. Marriage leads one into fibs by the very nature of it: all those temptations. One always orders too many gowns, and overspends one’s allowance. Not to mention men.” She kissed the tips of her fingers.

“But I wanted—”

“I am so pleased not to be married at the moment,” Zenobia said. “Not that I’m happy Etheridge died, of course. Ah well . . .”

Zenobia was gone.

And what Linnet wanted from marriage was clearly no longer a question worth discussion.

Once upon a time, not so very long ago . . .

(or, to be exact, March 1812)

. . . there was a girl who was destined to be a princess. Though to be absolutely precise, there was no prince in the offing. But she was betrothed to a duke’s heir, and from the point of view of minor gentry, a coronet was as good as a crown.

This story begins with that girl, and continues through a stormy night, and a series of tests, and if there’s no pea in the tale, all I can say is that if you read on, you

will

encounter a surprise in that bed: a key, a flea—or perhaps a marquess, for that matter.

In fairy tales, the ability to perceive an obtrusion as tiny as a pea under the mattress is enough to prove that a strange girl who arrives on a stormy night is indeed a princess. In the real world, of course, it’s a bit more complicated. In order to prepare for the rank of duchess, Miss Olivia Mayfield Lytton had learned something from virtually every branch of human knowledge. She was prepared to dine with a king, or a fool, or Socrates himself, conversing on subjects as far-flung as Italian comic opera and the new spinning machines.

But, just as a single dried pea was all that was needed to determine the authenticity of the princess, one crucial fact determined Olivia’s eligibility for the rank of duchess: she was betrothed to the heir to the Canterwick dukedom.

Less important were the facts that when this tale begins Olivia was twenty-three and still unmarried, that her father had no title, and that she had never been given a compliment such as

a diamond of the first water

. Quite the opposite, in fact.

None of that mattered.

In Which We Are Introduced to a Future Duchess

41 Clarges Street, Mayfair

London

The residence of Mr. Lytton, Esq.

M

ost betrothals spring from one of two fierce emotions: greed or love. But Olivia Lytton’s was fueled neither by an exchange of assets between like-minded aristocrats, nor by a potent mixture of desire, propinquity, and Cupid’s arrows.

In fact, the bride-to-be was liable, in moments of despair, to attribute her engagement to a curse. “Perhaps our parents forgot to ask a powerful fairy to my christening,” she told her sister Georgiana on their way home from a ball given by the Earl of Micklethwait, at which Olivia had spent generous swaths of time with her betrothed. “The curse, it hardly needs to be said, is Rupert’s hand in marriage. I would rather sleep for a hundred years.”

“Sleeping has its attractions,” her sister agreed, descending from their parents’ carriage before the house. Georgiana did not pair the positive comment with its opposite: sleep had attractions . . . but Rupert had few.

Olivia actually had to swallow hard, and sit in the dark carriage by herself a moment, before she was able to pull herself together and follow her sister. She had always known that she would be Duchess of Canterwick someday, so it made no sense to feel so keenly miserable. But there it was. An evening spent with her future husband made her feel half cracked.

It didn’t help that most of London, her mother included, considered her the luckiest of young women. Her mother would be horrified—though unsurprised—by Olivia’s lame jest linking the dukedom with a curse. To her parents, it was manifestly clear that their daughter’s ascension of the social ranks was a piece of singular good fortune. In short, a blessing.

“Thank God,” Mr. Lytton had said, oh, five thousand times since Olivia was born. “If I hadn’t gone to Eton . . .”

It was a story that Olivia and her twin sister Georgiana had loved when they were little. They would perch on their papa’s knees and listen to the thrilling tale of how he—plain, unremarkable (albeit connected to an earl on one side, as well as a bishop

and

a marquess on the other) Mr. Lytton—had gone to Eton and become best friends with the Duke of Canterwick, who had inherited his grand title at the tender age of five. At some point, the boys had sworn a blood oath that Mr. Lytton’s eldest daughter would become a duchess by marrying the Duke of Canterwick’s eldest son.

Mr. Lytton showed giddy enthusiasm in doing his part to ensure this eventuality, producing not one but two daughters within a year of marriage. The Duke of Canterwick, for his part, produced only one son, and that after a few years of marriage, but obviously one son was sufficient for the task at hand. Most importantly, His Grace kept his word, and regularly reassured Mr. Lytton about the destined betrothal.

Consequently, the proud parents of the duchess-to-be did everything in their power to prepare their firstborn daughter (the elder by a good seven minutes) for the title that was to be bestowed upon her, sparing no expense in shaping the future Duchess of Canterwick. Olivia was tutored from the moment she left the cradle. By ten years of age, she was expert in the finer points of etiquette, the management of country estates (including double-entry accounting), playing the harpsichord and the spinet, greeting people in various languages, including Latin (useful for visiting bishops, if no one else), and even in French cooking, though her knowledge of the last was intellectual rather than practical. Duchesses never actually touched food, except to eat it.

She also had a thorough knowledge of her mother’s favorite tome,

The Mirror of Compliments: A Complete Academy for the Attaining unto the Art of Being a Lady

, which was written by no less a personage than Her Grace, the Dowager Duchess of Sconce, and given to the girls on their twelfth birthday.

In fact, Olivia’s mother had read

The Mirror of Compliments

so many times that it had taken over her conversation, rather like ivy smothering a tree. “ ‘

Gentility

,’ ” she had said the morning before the Micklethwait ball over marmalade and toast, “ ‘

is bestowed on us by our ancestors, but soon blanched, when not revived by virtue

.’ ” Olivia had nodded. She herself was a firm believer in the benefits of blanching gentility, but long experience had taught her that expressing such an opinion would merely give her mother a headache.

“ ‘

A young lady

,’ ” Mrs. Lytton had announced on the way to the Micklethwait ball, “ ‘

loathes nothing so much as entering parley with an immodest suitor

.’ ” Olivia knew better than to inquire about how one “parleyed” with an immodest suitor. The

ton

understood that she was betrothed to the Duke of Canterwick’s heir, and therefore suitors, immodest or otherwise, rarely bothered to approach.

Generally speaking, she tabled that sort of advice for the future, when she hoped to indulge in any number of immodest parleys.

“Did you see Lord Webbe dancing with Mrs. Shottery?” Olivia asked her sister as they walked into her bedchamber. “It’s quite affecting to watch them stare into each other’s eyes. I must say, the

ton

seems to take their wedding vows about as seriously as do the French, and everyone says that inclusion of marital fidelity into French wedding vows turned them a splendid work of fiction.”

“

Olivia

!” Georgiana groaned. “You mustn’t! And you wouldn’t—would you?”

“Are you asking whether I will ever be unfaithful to my fiancé once he’s my husband—if that day ever arrives?”

Georgiana nodded.

“I suppose not,” Olivia said, though secretly she sometimes wondered if she might just snap one day and break every social rule by running off to Rome with a footman. “The only part of the evening I really enjoyed was when Lord Pomtinius told me a limerick about an adulterous abbot.”

“Don’t you

dare

repeat it!” her sister ordered. Georgiana had never shown the faintest wish to rebel against the rules of propriety. She loved and lived by them.

“There once was an adulterous abbot,” Olivia teased, “as randy—”

Georgiana slapped her hands over her ears. “I can’t believe he told you such a thing! Father would be furious if he knew.”

“Lord Pomtinius was in his cups,” Olivia said. “Besides, he’s ninety-six and he doesn’t care about decorum any longer. Just a laugh, now and then.”

“It doesn’t even make sense. An adulterous abbot? How can an abbot be adulterous? They don’t even marry.”

“Let me know if you want to hear the whole verse,” Olivia said. “It ends with talk of nuns, so I believe the word was being used loosely.”

That limerick—and Olivia’s appreciation of it—pointed directly to the problem with Miss Lytton’s duchess-ification, or, as the girls labeled it, “duchification.” There was something very

déclassé

about Olivia, no matter how proper her bearing, her voice, and her manners might be. She certainly could play the duchess, but the real Olivia was, dismayingly, never far from the surface.

“You are missing that indefinable air of consequence that your sister conveys without effort,” her father often opined, with an air of despondent resignation. “In short, Daughter, your sense of humor tends toward the vulgar.”

“ ‘

Your demeanor should ever augment your honor

,’ ” her mother would chime in, quoting the Duchess of Sconce.

And Olivia would shrug.

“If only,” Mrs. Lytton had said despairingly to her husband time and again, “if only

Georgiana

had been born first.” For Olivia was not the only participant in the Lytton training program. Olivia and Georgiana had marched in lockstep through lessons on the comportment of a duchess, because their parents, aware of the misfortunes that might threaten their eldest daughter—a fever, a runaway carriage, a fall from a tower—had prudently duchified their second-born as well.

Sadly, it was manifest to everyone that Georgiana

had

achieved the quality of a duchess, while Olivia . . . Olivia was Olivia. She certainly could behave with exquisite grace—but among her intimates, she was sarcastic, far too witty to be ladylike, and not in the least gracious. “She looks at me in

such

a way if I merely mention

The Mirror of Compliments

,” Mrs. Lytton would complain. “I’m only trying to help, I’m sure.”

“That girl will be a duchess someday,” Mr. Lytton would say heavily. “She’ll be grateful to us then.”

“But if

only

. . . ,” Mrs. Lytton would say, wistfully. “Dearest Georgiana is just . . . well, she would be a perfect duchess, wouldn’t she?”

In fact, Olivia’s sister had mastered early the delicate art of combining a pleasing air of consequence with an irreproachably modest demeanor. Over the years Georgiana had built up a formidable array of duchess-like traits: ways of walking, talking, and carrying herself.

“ ‘

Dignity, virtue, affability, and bearing

,’ ” Mrs. Lytton recited over and over, turning it into a nursery rhyme.

Georgiana would glance at the glass, checking her dignified bearing and affable expression.

Olivia would sing back to her mother: “Debility, vanity, absurdity, and . . .

brainlessness

!”

By eighteen years of age, Georgiana looked, sounded, and even smelled (thanks to French perfume, smuggled from Paris at great expense) like a duchess. Mostly, Olivia didn’t bother.

The Lyttons were happy, in a measured sort of way. By any sensible standard they had produced a real duchess, even if that particular daughter was not betrothed to a duke’s heir. As their girls were growing up, they told themselves that Georgiana would make a lovely wife to any man of rank. Alas, in time they stopped saying anything about their second daughter’s hypothetical husband.

The sad truth is that a duchified girl is not what most young men desire. While Georgiana’s virtues were celebrated far and wide throughout the

ton

—especially amongst the dowager set—her hand was rarely sought for a dance, let alone for marriage.

Mr. and Mrs. Lytton interpreted the problem differently. To their mind, their beloved second daughter was likely to dwindle into the shadow of a duchess, without becoming even a wife, because she had no dowry.

The Lyttons had spent all their disposable income on tutors. That had left their younger daughter with little more than a pittance to launch her on the marriage market.

“We have sacrificed everything for Olivia,” Mrs. Lytton often said. “I can’t understand why she is not more grateful. She’s the luckiest girl in England.”

Olivia did not view herself as lucky at all.

“The

only

reason I can countenance marrying Rupert,” she said to Georgiana, “is that I will be able to dower you.” She stripped off her gloves, biting the tips to pull them from her fingers. “To be honest, the mere thought of the wedding makes me feel slightly mad. I could bear the rank—though it isn’t my cup of tea, to say the least—if he weren’t such a little, beardy-weirdy bottle-headed chub.”

“You’re using slang,” Georgiana said. “And—”

“Absolutely not,” Olivia said, throwing her gloves onto her bed. “I made it up myself, and you know as well as I do that the

Mirror for Bumpkins

says that slang is—and I quote—‘

grossness of speech used by the lowest degenerates in our nation

.’ Much though I would like to attain the qualifications of a degenerate, I have no hope of achieving that particular title in this life.”

“You shouldn’t,” Georgiana said, arranging herself on the settee before Olivia’s fireplace. Olivia had been given the grandest bedchamber in the house, larger than either their mother’s or father’s chambers, so the twins generally hid from their parents in Olivia’s room.

But the reprimand didn’t have its usual fire. Olivia frowned at her sister. “Was it a particularly rotten night, Georgie? I kept getting swept away by my dim-witted fiancé, and after supper I lost track of you.”

“I would have been easy to find,” Georgiana replied. “I sat among the dowagers most of the night.”

“Oh, sweetheart,” Olivia said, sitting down next to her sister and giving her a fierce hug. “Just wait until I’m a duchess. I’ll dower you so magnificently that every gentleman in the country will be on bended knee at the very thought of you. ‘Golden Georgiana,’ they’ll call you.”

Georgiana didn’t even smile, so Olivia forged ahead. “I like sitting with the dowagers. They have all the stories one would really like to hear, like that one about Lord Mettersnatch paying seven guineas to be flogged.”