Winter Soldier (10 page)

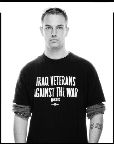

Authors: Iraq Veterans Against the War,Aaron Glantz

Tags: #QuarkXPress, #ebook, #epub

Instead of a soldier, I’m a “soulja” now, you know. I’ve switched it around. I’d like to just give this little poem now:

And that’s what I feel we’re doing now.

Whenever incidents that spotlight the gross inhumanity of the U.S. occupation of Iraq leak into the media, they’re quickly dismissed as isolated incidents, condemned by generals and politicians alike. “The actions of these few people do not reflect the hearts of the American people,” President Bush intoned after the Abu Ghraib prison scandal broke in 2004. “What took place in that prison does not represent the America that I know.” The president also promised a swift investigation, promising those responsible would be “brought to justice.”1

Two years later, the same kinds of comments came from Washington after Time magazine reported the massacre of twenty-four Iraqi civilians in Haditha. U.S. military spokesman Major General William Caldwell told reporters that while “temptation exists to lump all these incidents together…each case needs to be examined individually.”2

Administration and Pentagon officials refuse to investigate why similar acts of brutality occur again and again, because they know that kind of thoughtful inquiry would lead to a damning indictment of the occupation itself. That’s why, throughout the U.S. occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan, administration and Pentagon officials have assiduously avoided asking questions implicitly raised by veterans at Winter Soldier: Why do these seemingly senseless killings occur? What makes them possible? What brings otherwise normal young men and women to the point of committing terrible atrocities? As you’ll see in the chapter that follows, the answer begins with the dehumanizing nature of military training itself.

Twenty-three-year-old Robert Zabala joined the Marine Corps thinking it would be a “place where he could find security” after the death of his grandmother. But when he began boot camp in June 2003, Zabala said he was appalled by the Marine Corps’ attempts to desensitize the recruits to violence.

“The response that all the recruits are supposed to say is ‘kill,’” he told San Francisco’s KGO-TV. “So in unison you have maybe 400 recruits chanting ‘kill, kill, kill,’ and after a while that word becomes almost nothing to you. What does it mean? You say it so often you really don’t think of the consequences of what it means to say ‘kill’ over and over again as you’re performing this deadly technique, a knife to the throat.”3

When Zabala realized he couldn’t kill another human being, he submitted an application for conscientious objector status to the Marine Corps Reserve. But Zabala’s platoon commander denied his request: “What did you think you were joining, the Peace Corps?” court documents quote Major R.D. Doherty as saying. “I don’t know how anyone who joins the Marine Corps cannot know that it involves killing.”

Zabala sued and on March 29, 2007, a federal judge in Northern California overruled the military justice system, ordering the Marine Corps to discharge Zabala as a conscientious objector within fifteen days. In his ruling, U.S. District Court Judge James Ware noted Zabala’s experiences with his first commander, Captain Sanchez. During basic training, Sanchez repeatedly gave speeches about “blowing shit up” or “kicking some fucking ass.” In 2003, when a fellow recruit committed suicide on the shooting range, Sanchez commented in front of the recruits, “fuck him, fuck his parents for raising him, and fuck the girl who dumped him.”

Another boot camp instructor showed recruits a “motivational clip” displaying Iraqi corpses, explosions, gun fights, and rockets set to a heavy-metal song that included the lyrics, “Let the bodies hit the floor,” the petition said. Zabala said he cried while other recruits nodded their heads in time to the beat.4

This pattern of abusive, reflexive, purposely dehumanizing training is not unique to the Iraq war, the Marine Corps, or Robert Zabala. It’s the way the U.S. military has trained its troops for fifty years, the results of research published by the noted military historian, U.S. Army Brigadier General S.L.A. Marshall, who surveyed veterans after World War II.

General Marshall asked these average soldiers what they did in battle. Unexpectedly, he discovered that for every hundred men along the line of fire in battle, only fifteen to twenty actually discharged their weapons. “The average healthy individual,” Marshall wrote, “has such an inner and unusually unrealized resistance toward killing a fellow man that he will not of his own volition take life if it is possible to turn away from that responsibility. … At the vital point [the soldier] becomes a conscientious objector.”5

Marshall’s findings shocked the military and caused the Armed Forces to change their training regimen dramatically. By the Vietnam War, Pentagon studies showed 90 percent of servicemembers in combat fired their weapons.

Forcing new recruits to chant “kill, kill, kill” became common practice. The idea was to have the idea of death drilled so deeply in the mind of the servicemember that when he or she was asked to take another human life, it didn’t bother them. The military also began conditioning soldiers to develop a reflexive “quick shoot” ability. In training, recruits were taught to fire their weapons without thinking about who might be killed.

“Instead of lying prone on a grassy field calmly shooting at a bulls-eye target,” Army Lieutenant Colonel David Grossman wrote in his book On Killing, “the modern soldier spends many hours standing in a foxhole, with full combat equipment draped about his body looking over an area of lightly wooded rolling terrain. At periodic intervals one or two olive-drab, man-shaped targets at varying vantages will pop up in front of him for a brief time and the soldier will instantly aim and shoot at the targets.”6

The idea is to dehumanize the enemy. “Under such conditions,” wrote the noted Stanford University psychologist Philip Zimbardo, “it becomes possible for normal, morally upright and even idealistic people to perform acts of destructive cruelty.”7

The result of this training can be seen every day in Iraq and Afghanistan. In a May 2007 Pentagon survey of U.S. troops in combat in Iraq, less than half of soldiers and marines said they felt they should treat noncombatants with respect. Only about half said they would report a member of their unit for killing or wounding an innocent civilian. More than 40 percent supported the idea of torture.

Overt, institutionalized racism from the command also plays an important role in distancing soldiers and marines from the people they kill. This system did not begin with the occupation of Iraq or inside the U.S. military. It is as old as war itself. In the 1930s, Nazi propaganda films depicted Jews as rodents. During the Rwandan genocide, ethnic Tutsis referred to the Hutus they slaughtered as “insects” or cockroaches. During the 1960s and ’70s, American soldiers dehumanized the Vietnamese people by calling them “gooks.” Today, members of the U.S. Armed Forces regularly refer to Iraqi and Afghan civilians as “hajis” and “towel-heads.”

This dehumanizing group pressure is so strong that even Arabs and Muslims inside the Armed Forces adopt racial epithets to describe the “enemy.” During the Racism and Dehumanization panels at Winter Soldier, David Hassan sat in the back of the room nodding in agreement. The former marine, whose father is Egyptian, had grown out his beard and wore a black-and-white checkered keffiyeh around his head. He served in Anbar province doing electronic surveillance and translated interrogations in 2005.

“I used the word [haji],” Hassan told me. “The military’s not just a job, it’s a culture. It pervades every aspect of your life and when you’re surrounded by it 24 hours a day the culture seeps into you, and I guess—in retrospect—I had to adopt the dehumanizing of the Iraqi people to be okay with what I was a part of.”

But like the other veterans at Winter Soldier, Hassan said he couldn’t be a part of that dehumanization anymore. “I feel an obligation to speak out against this war,” he said. “I feel like I was sold, for the majority of my life, a fallacious view of what war is and what war does to people and having seen that that’s a lie—I have an obligation to speak out against it.”

Specialist, United States Army, Military Police, 716th Military Police Battalion, 101st Airborne Brigade

Deployment: April 2003–April 2004, Karbala

Hometown: Rochester, New York

Age at Winter Soldier: 26 years old

For the first six months of my deployment, I served as a driver for a security vehicle for my command sergeant major and my lieutenant colonel, and for the last six months I was put back in the line platoon for the 194th MP Company.

This is me in Babylon, early on in the deployment. These are some ancient ruins, thousands of years old and this slide highlights the lack of respect that we had for the ancient culture and for the culture in Iraq, and it displays our insensitivity to the people of Iraq.

When I first arrived in Iraq, I was stationed in one of Saddam’s palaces in Baghdad. I had a picture taken of me pointing to my American flag, thinking to myself, “Good job,” and being very proud of my country. This highlights the arrogance that I had in this point in my life. It displays the heightened sense of importance that I felt and that many in my unit felt. This arrogance permits us to do harm to the Iraqi people and to treat them as second-class citizens.

I have a few talking points. I’m going to highlight that sense of importance and my unit’s general attitude toward the Iraqi people. Then I’m going to go into some specifics.

I worked with my command sergeant major often and he would provide mission briefs and after action reviews for every mission that we were on. During many of these mission briefs, we used language such as “haji”—which is an Arabic term of endearment that the military has turned on its head. My command sergeant major, in one specific mission brief, said to the nine-person team, “Haji is an obstacle, do not let them get in our way,” meaning that if they drove in front of us, drive through them.

At one point in the deployment, when I was on a convoy just north of Baghdad, I pulled over to have an MRE and refuel our trucks. It was about a six-vehicle convoy. Oftentimes kids in the surrounding community would run up to us and say, “Thank you, thank you,” and welcome us with warm arms. We didn’t want that kind of attention from the kids, for fear of their safety, because we knew we were targeted in that country.