With Liberty and Justice for Some (25 page)

Read With Liberty and Justice for Some Online

Authors: Glenn Greenwald

The members of the political and media establishment do not join forces against the investigations and prosecutions because they believe that nothing bad was done. On the contrary, they resist accountability precisely because they know there was serious wrongdoing—and they know they bear part of the culpability for it. The consensus mantra that the only thing that matters is to “make sure it never happens again” is simply the standard cry of every criminal desperate for escape: I promise not to do it again if you don’t punish me this time. And the Beltway battle-cry of “look to the future, not the past!” is what all political power systems tell their subjects to do when they want to flush their own crimes down the memory hole.

In the long run, immunity from legal accountability ensures that criminality and corruption will continue. Vesting the powerful with license to break the law guarantees high-level lawbreaking; indeed, it encourages such behavior. One need only look at what’s happened in the United States over the last decade to see the proof.

5

5

When ordinary Americans come in contact with the justice system, everything changes. The world we have been examining reverses. In the United States, the lack of accountability for elites goes hand-in-hand with a lack of mercy for everyone else. As our politicians increasingly claim the right to commit crimes with impunity, they simultaneously escalate the severity of punishments imposed on ordinary Americans who have broken even minor laws.

As a result, precisely what the founders most feared has come to exist: a two-tiered system of justice in which outcomes are determined not by the law itself but by the status, wealth, and power of the lawbreaker. And these days, the people advocating for elite immunity are often the same ones who emphatically insist upon rigid, unyielding enforcement of the rules for the rest of us. Indeed, when it comes to crime and punishment, the trends for powerful and ordinary Americans have been heading in completely divergent directions. During the same four-decade period in which the nation’s political class has expanded legal immunity for political and financial elites, it has imposed ever-harsher prison terms on more and more of the nation’s citizens.

Permissiveness for elites, by itself, is unjust enough. But at least if that leniency were available on an equal basis to everyone, it might arguably be fair, and certainly less injurious to basic precepts of justice. It is the elites’ insistence on treating all others in precisely the opposite fashion from the way they treat themselves that is so pernicious.

The United States now imprisons more of its citizens than any other nation in the world, both per capita and in absolute terms. The numbers are staggering. The United States has only 5 percent of the world’s population, yet nearly 25 percent of all prisoners in the world are on American soil. “Simply put, we have become a nation of jailers,” writes the Brown University professor Glenn Loury. “The American prison system has grown into a leviathan unmatched in human history.”

According to the King’s College International Centre for Prison Studies, at the end of 2008 the United States was incarcerating more than 2.2 million of its citizens in federal and state prisons and local jails around the nation. In July 2010, the

Economist

similarly put the number at “between 2.3 and 2.4 million.” The nation with the next-largest prison population, China, has 1.6 million people in prison—which means that the United States, a nation of 300 million, imprisons 700,000 more of its citizens than a country whose population is 1.3 billion. And that number is continuing to increase. As a 2007 report from the JFA Institute described it, “If you put them all together in one place, the incarcerated population [of the United States] in just five years will outnumber the residents of Atlanta, Baltimore and Denver combined.”

The United States also has the highest rate of imprisonment of any nation in the world, with 756 people in prison per 100,000 citizens. The next-highest rates belong to Russia (629) and Rwanda (604). The rates in most of the world are far lower. The median imprisonment rate for South American countries is 154; for western Europe, 95; and for western African countries, 35. On a per capita basis, the United States is practically in a league by itself.

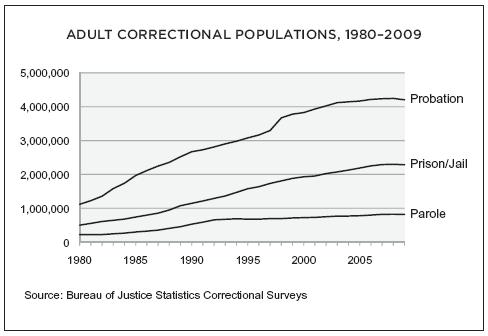

America’s overall “correctional population”—which includes not just those in prison but also people on probation and on supervised parole—is even more enormous and continues to grow. According to Justice Department statistics, at the end of 2008 over 7.3 million people—one in every thirty-one U.S. adults—were on probation, in jail or prison, or on parole. And that’s not even counting the nation’s 4.3 million ex-convicts who have fulfilled their parole obligations.

Worse, American criminal justice policy has been trending in only one direction: toward ever more prosecutions, convictions, and imprisonments. Over the last forty years, the growth in America’s prison state has been unremitting. (The total adult correctional population decreased very slightly in 2009 after decades of uninterrupted growth, but the reduction was so small that it was most likely a statistical aberration rather than the result of any policy changes.) In 1970, fewer than 190,000 people were incarcerated in the United States; since then, we have seen more than a tenfold increase. In 2008, when Pew released a comprehensive report on America’s prison state, it reported that “for the first time in history more than one in every 100 adults in America are in jail or prison.” The increase in probation and parole numbers has been similarly dramatic.

These trends have continued right through periods of rising crime and falling crime, prosperity and economic hardship, war and peace, Democratic and Republican rule. In 2007, the JFA Institute noted that “prison populations have been growing steadily for a generation, although the crime rate is today about what it was in 1973 when the prison boom started.” Indeed, as the institute put it, “most scientific evidence suggests that there is little if any relationship between fluctuations in crime rates and incarceration rates. In many cases, crime rates have risen or declined independent of imprisonment rates.”

Clearly, the growth in prison populations is not a response to national circumstances. What it represents, rather, is a deliberate choice by the political class to lock up more and more people for longer periods and for ever more trivial offenses. While wealthy and powerful Americans are increasingly able to avoid suffering any consequences for their lawbreaking, ordinary Americans have had little means to resist the punitive onslaught.

“Law-and-Order” Extremism Goes Bipartisan

The American prison system began its expansion in the 1960s, when the right wing of the Republican Party, led by presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, vowed to make “the abuse of law and order in this country” a central issue. In Republican parlance, this meant more aggressive policing, longer prison sentences, stricter criteria for parole and probation, and less leniency in general. Social unrest in the 1960s—the civil rights movement, antiwar protests, assassinations, and urban race riots—further increased the appeal of a law-and-order platform. Ronald Reagan rode that sentiment to the California governorship in 1966, and Richard Nixon, who would be the beneficiary of extreme leniency a mere six years later, drove it hard to become president in 1968.

Conservative politicians often used appeals to law and order to mask their opposition to social welfare programs, such as Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. Goldwater, for example, repeatedly blamed the welfare state for what he insisted (without much evidence) was America’s growing crime problem.

If it is entirely proper for the government to take away from some to give to others, then won’t some be led to believe that they can rightfully take from anyone who has more than they? No wonder law and order has broken down, mob violence has engulfed great American cities, and our wives feel unsafe in the streets.

Johnson, for his part, attempted to sell his sweeping social programs to America’s middle class by packaging them as a law-and-order solution. Poverty was the root cause of lawbreaking, he argued, and consequently alleviating it would reduce crime.

From the outset, issues of race as well as class pervaded discussions of criminality. With the civil rights movement rendering overt expressions of racial prejudice less acceptable, opponents of racial equality channeled their animus into law-and-order rhetoric. In 1966, Nixon blamed societal decline on the civil disobedience of Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders, arguing that “the deterioration of respect for the rule of law can be traced directly to the spread of the corrosive doctrine that every citizen possesses an inherent right to decide for himself which laws to obey and when to disobey them.” Meanwhile, focusing on the root causes of crime was derided by the Republicans as a destructive liberal delusion. Gerald Ford, the House minority leader at the time, demanded to know, “How long are we going to abdicate law and order in favor of a soft social theory that the man who heaves a brick through your window or tosses a firebomb into your car is simply the misunderstood and underprivileged product of a broken home?”

Over the following decades, the law-and-order mentality of the 1960s became one of the most influential forces in American political culture, consistently targeting the poorest, most marginalized, and most powerless Americans. In the 1970s, Nixon regularly maligned the Warren Court as one of society’s prime villains. Its sin: recognizing a slew of constitutional rights and establishing various safeguards for criminal defendants, including the right to have improperly obtained evidence or coerced confessions excluded from trial (

Mapp v. Ohio

and

Escobedo v. Illinois

), the right of indigent defendants to have counsel provided for them (

Gideon v. Wainright

), and the right to be told about one’s rights upon being taken into custody (

Miranda v. Arizona

). Scapegoating judicial and political liberalism as the prime cause of crime, Nixon dramatically increased the power and scope of federal law enforcement agencies—most notably with the 1973 creation of the Drug Enforcement Agency. He also made adherence to law-and-order ideology the primary consideration in his judicial selections, including the appointment of conservatives Warren Burger and William Rehnquist to the Supreme Court.

Notably, Ford’s pardon of Nixon in 1974 did little to stem the rising tide of law-and-order enthusiasm. By the time Reagan was elected president in 1980, appeals to law and order were a constant refrain in American politics. Reagan made attacks on excessive “leniency” a vital part of his campaign against Jimmy Carter. And once in office, he replaced the Warren Court with a new scapegoat: the Cadillac-driving welfare queen, a caricature meant to represent a scheming and dishonest underclass. As the criminology scholars Katherine Beckett and Theodore Sasson document in their book

The Politics of Injustice

, within the first year of Reagan’s presidency his attorney general, William French Smith, slashed resources devoted to prosecuting white-collar crimes and domestic violence and “began to pressure federal law enforcement agencies to shift their focus…to street crime.”

Most significant for the growth of America’s penal state was the federal government’s increased emphasis on the “war on drugs.” “The drug problem has become so widespread that the FBI must assume a larger role in attacking the problem,” declared FBI director William Webster in 1981. The DEA grew very rapidly in the 1980s, relocating from a modest downtown Washington building into a sprawling northern Virginia complex. Strident warnings about the drug trade, particularly the melodramatic 1980s media jeremiads about the “crack epidemic,” further fueled the law-and-order movement. Multiple new laws, including the Anti-Drug Abuse acts of 1986 and 1988, imposed draconian minimum sentence requirements on those convicted of trafficking in illicit substances or even merely possessing relatively small amounts of them.

But it was the 1988 presidential election that cemented law and order as American orthodoxy. A prime cause for the defeat of Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis was the George Bush campaign’s vilification of the Massachusetts governor as “soft on crime,” which it accomplished through the infamous television ad featuring Willie Horton. Horton, a menacing-looking African American convicted murderer, had received a weekend furlough from prison as part of a program supported by Dukakis, and while on furlough had raped a white woman in front of her husband. In the

Washington Post

, the reporter Sidney Blumenthal quoted a Bush campaign aide exulting over the Horton episode as “a wonderful mix of liberalism and a big black rapist.” Further cementing Dukakis’s “soft-on-crime” image was a presidential debate in which CNN’s Bernard Shaw asked the candidate whether he would continue to oppose the death penalty if his own wife were raped and murdered. The uncharismatic Democrat responded by dispassionately enumerating the policy flaws of the death penalty, a stoic reaction which led to widespread accusations that he lacked “manly emotions.”

The Dukakis fiasco doomed any efforts to curb law-and-order extremism. There was little to gain, and much to lose, for any politician advocating moderation in criminal punishment of the marginalized.

Bill Clinton left no doubt that he had learned the lesson. Branding himself a “New Democrat” during the 1992 presidential campaign, he touted his unflinching belief in “tough-on-crime” measures, declaring that Democrats “should no longer feel guilty about protecting the innocent.” To underscore the point, the Arkansas governor left the campaign trail to preside over the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, an African American convicted murderer who was functionally retarded and entirely incapable of understanding what was taking place. Clinton’s carefully crafted crime-warrior image protected him against the racially charged attacks that destroyed Dukakis and was an important factor in his victory over the incumbent, President Bush.