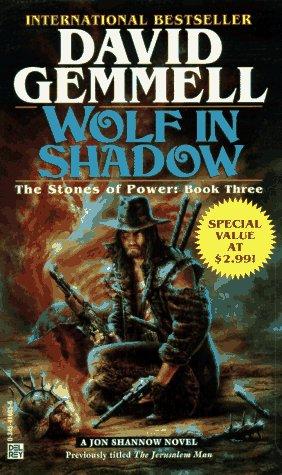

Wolf In Shadow

Authors: David Gemmell

Stones of Power 3 - Wolf in Shadow

PROLOGUE

The High Priest lifted his bloodstained hands from the corpse and dipped them in a silver bowl filled with scented water. The blood swirled around the rose petals floating there, darkening them and glistening like oil. A young acolyte moved to kneel before the King, his hands outstretched. The King leaned forward, placing a large oval stone in his palms. The stone was red-gold, and veined with thick black streaks. The acolyte carried the stone to the corpse, laying it on the gaping wound where the girl’s heart had been. The stone glowed, the red-gold gleaming like an eldritch lantern, the black veins shrinking to fine hairlines. The acolyte lifted the stone once more, wiped it with a cloth of silk and returned it to the King before backing away into the shadows.

A second acolyte approached the High Priest, bowing low. In his arms he held the red ceremonial cape which he lifted over the priest’s bald head.

The King clapped his hands twice and the girl’s body was lifted from the marble altar and carried down the long hall to oblivion.

’Well, Achnazzar?’ demanded the King.

’As you can see, my lord, the girl was a powerful ESPer, and her essence will feed many Stones before it fades.’

’The death of a pig will feed a Stone, priest. You know what I am asking,’ said the King, fixing Achnazzar with a piercing glare. The bald priest bowed low, keeping his eyes on the marble floor.

’The omens are mostly good, sire.’

’Mostly? Look at me!’ Achnazzar raised his head, steeling himself to meet the burning eyes of the Satanlord. The priest blinked and tried to look away, but Abaddon’s glare held him trapped, almost hypnotized. ’Explain yourself.’

The invasion, Lord, should proceed favorably in the Spring. But there are dangers . . . not great dangers,’ he added hurriedly.

’From which area?’

Achnazzar was sweating now as he licked dry lips with a dry tongue.

’Not an area, Lord, but three men.’

’Name them.’

’Only one can be identified, the others are hidden. But we will find them. The one is called Shannow. Jon Shannow.’

’Shannow? I do not know the name. Is he a leader of men, or a Brigand chief?’

’No, Lord. He rides alone.’

’Then how is he a danger to the Hellborn?’

’Not to the Hellborn, sire, but to you.’

’You consider there is a difference?’

Achnazzar blanched and blinked the sweat from his eyes. ‘No, Lord, I meant merely that the threat is to you as a man.’

’I have never heard of this Shannow. Why should he threaten me?’ ‘There is no sure answer, sire, but he follows the old, dead god.’

’A Christian?’ spat Abaddon. ‘Will he seek to kill me with love?’

’No, Lord, I meant the old dark god. He is a Brigand-slayer, a man of sudden violence. There is even some indication that he is insane.’

’How do these indications manifest themselves - apart from his religious stupidity?’

’He is a wanderer, Lord, searching for a city which ceased to exist during Blessed Armageddon.’

’What city?’

’Jerusalem, Lord.’

Abaddon chuckled and leaned back on his throne, all tension fading. ‘That city was destroyed by a tidal wave three hundred years ago - by the great mother of all tidal waves. A thousand feet of surging ocean drowned that pestilential place, signaling the rein of the Master and the death of Jehovah. What does Shannow hope to find in Jerusalem?’

’We do not know, Lord.’

’And why is he a threat?’

’In every chart, or seer-dream, his line crosses yours. Karmically you are bonded. It is so with the other two; in some way Shannow has touched - or will touch - the lives of two men who could harm you. We cannot identify them yet - but we will. For now they appear as shadows behind the Jerusalem Man.’

’Shannow must die … and swiftly. Where is he now?’

’He is at present some months’ journey to the south, nearing Rivervale. We have a man there, Fletcher. I shall get word to him.’

’Keep me informed, priest.’

As Achnazzar backed away from his monarch, Abaddon rose from the ebony throne and wandered to the high arched window, gazing over New Babylon. On a plain to the south of the city the Hellborn army was gathering for the Raids of the Blood Feast. By Winter the new guns would be distributed and the Hellborn would ready themselves for the Spring war: ten thousand men under the banner of Abaddon, sweeping into the south and west, bringing the new world into the hands of the last survivor of the Fall.

And they warned him of one madman?

Abaddon raised his arms. ‘Come to me, Jerusalem Man.’

The rider paused at the crest of a wooded hill and gazed down over the wide rolling empty lands beneath him.

There was no sign of Jerusalem, no dark road glittering with diamonds. But then Jerusalem was always ahead, beckoning in the dreams of night, taunting him to find her on the black umbilical road.

His disappointment was momentary and he lifted his gaze to the far mountains, grey and spectral. Perhaps there he would find a sign? Or was the road covered now by the blown dust of centuries, disguised by the long grass of history?

He dismissed the doubt; if the city existed, Jon Shannow would find it. Removing his wide-brimmed leather hat, he wiped the sweat from his face. It was nearing noon and he dismounted. The steeldust gelding stood motionless until he looped the reins over its head, then dipped its neck to crop at the long grass. The man delved into a saddlebag to pull clear his ancient Bible; he sat on the ground and idly opened the gold-edged pages.

’And Saul said to David, Thou art not able to go against this Philistine to fight with him, for thou art but a youth, and he is a man of war from his youth.’

Shannow felt sorry for Goliath, for the man had had no chance. A courageous giant, ready to face any warrior, found himself opposite a child without sword or armour. Had he won, he would have been derided. Shannow closed the Bible and carefully packed it away.

Time to move,’ he told the gelding. He stepped into the saddle and swept up the reins. Slowly they made their way down the hillside, the rider’s eyes watchful of every boulder and tree, bush and shrub. They entered the cool of the valley and Shannow drew back on the reins, turning his face to the north and breathing deeply.

A rabbit leapt from the brush, startling the gelding. Shannow saw the creature vanish into the undergrowth and then uncocked the long-barrelled pistol, sliding it back into the scabbard at his hip. He could not recall drawing it clear. Such was the legacy of the years of peril - fast hands, a sure eye and a body that reacted independently of the conscious mind.

Not always a good thing . . . Shannow would never forget the look of blank incomprehension in the child’s eyes as the lead ball clove his heart. Nor the way his frail body had crumpled lifeless to the earth. There had been three Brigands that day and one had shot Shannow’s horse out from under him, while the other two ran forward with knife and axe. He had destroyed them all in scant seconds, but a movement behind caused him to swivel and fire. The child had died without a sound.

Would God ever forgive him?

Why should he, when Shannow could not forgive himself?

’You were better off losing, Goliath,’ said Shannow.

The wind changed and a stomach-knotting aroma of frying bacon drifted to him from the east. Shannow tugged the reins to the right. After a quarter of a mile the trail rose and fell and a narrow path opened on to a meadow and a stone-fronted farmhouse. Before the building was a vegetable garden and beyond it a paddock where several horses were penned.

There were no defence walls and the windows of the house were wide and open. To the left of the building the trees had been allowed to grow to within twenty yards of the wall, allowing no field of fire to repel Brigands. Shannow sat and stared for some time at this impossible dwelling. Then he saw a child carrying a bucket emerge from the barn beyond the paddock. A woman walked out to meet him and ruffled his blond hair.

Shannow scanned the fields and meadows for sign of a man. At last, satisfied that they were alone, he edged the gelding out on to open ground and approached the building. The boy saw him first and ran inside the house.

Donna Taybard’s heart sank as she saw the rider and she fought down panic as she lifted the heavy crossbow from the wall. Placing her foot in the bronze stirrup she dragged back on the string, but could not notch it.

’Help me, Eric.’ The boy joined her and together they cocked the weapon. She slid a bolt into place and stepped on to the porch. The rider had halted some thirty feet from the house and Donna’s fear swelled as she took in the gaunt face and deep-set eyes, shadowed under the wide-brimmed hat. She had never seen a Brigand, but had anyone asked her to imagine one this man would have leapt from her nightmares. She lifted the crossbow, resting the heavy butt against her hip.

’Ride on,’ she said. ‘I have told Fletcher we shall not leave, and I will not be forced.’

The rider sat very still, then he removed his hat. His hair was shoulder-length and black, streaked with silver, and his beard showed a white fork at the chin.

’I am a stranger, Lady, and I do not know this Fletcher. I do not seek to harm you - I merely smelt the bacon and would trade for a little. I have Barta coin and . . .’

’Leave us alone,’ she shouted. The crossbow slipped in her grip, dropping the trigger bar against her palm. The bolt flashed into the air, sailing over the rider and dropping by the paddock fence. Shannow walked his horse to the paddock and dismounted, retrieving the bolt. Leaving the gelding, he strolled back to the house.

Donna dropped the bow and pulled Eric into her side. The boy was trembling, but in his hand he held a long kitchen knife; she took it from him and waited as the man approached. As he walked he removed his heavy leather top-coat and draped it over his arm. It was then that she saw the heavy pistols at his side.

’Don’t kill my boy,’ she said.

’Happily, Lady, I was speaking the truth: I mean you no harm. Will you trade a little bacon?’ He picked up the bow and swiftly notched it, slipping the bolt into the gulley. ‘Would you feel happier carrying this around?’

’You are truly not with the Committee?’

’I am a stranger.’

’We are about to take food. If you wish, you may join us.’

Shannow knelt before the boy. ‘May I enter?’ he asked.

’Could I stop you?’ returned the boy bitterly.

’With just one word.’

’Truly?’

’My faults are many, but I do not lie.’

’You can come in then,’ said the boy and Shannow walked ahead with the child trailing behind. He mounted the porch steps and entered the cool room beyond, which was spacious and well-constructed. A white stone hearth held a wood-stove and an iron oven; at the centre of the room was a handsomely carved table and a wooden dresser bearing earthenware plates and pottery mugs.

’My father carved the table,’ said the boy. ‘He is a skilled carpenter - the best in Rivervale - and his work is much sought after. He made the comfort chair, too, and cured the hides.’ Shannow made a show of admiring the leather chair by the wood-stove, but his eyes followed the movements of the petite blonde woman as she prepared the table.

Thank you for allowing me into your home,’ said Shannow gravely. She smiled for the first time and wiped her hand on her canvas apron.

’I am Donna Taybard,’ she told him, offering her hand. He took it and kissed her fingers lightly.

’And I am Jon Shannow - a wanderer, Lady, in a strange land.’

’Be welcome then, Jon Shannow. We have some potatoes and mint to go with the bacon, and the meal will be ready within the hour.’

Shannow moved to the door, where pegs had been hammered home. He unbuckled his scabbard belt and hung his sidearms beside his coat. Turning back, he saw the fear once more in her eyes.

’Be not alarmed, Fray Taybard; a wandering man must protect himself. It does not change my promise; that may not be so with all men, but my spoken word is iron.’

There are few guns in Rivervale, Mr Shannow. This was . . . is . . .a peaceful land. If you would like to wash before eating, there is a pump behind the house.’

’Do you have an axe, Lady?’

’Yes. In the wood-shed.’

’Then I shall work for my supper. Excuse me.’

He walked out into the fading light of dusk and unsaddled the gelding, leading him into the paddock and releasing him among the other three horses. Then he carried his saddle and bags to the porch before fetching the axe. He spent almost an hour preparing firewood before stripping to the waist and washing himself at the pump. The moon was up when Donna Taybard called him in. She and the boy sat at one end of the table, having set his place apart and facing the hearth. He moved his plate to the other side and seated himself facing the door.

’May I speak a word of thanks, Fray Taybard?’ asked Shannow as she filled the plates. She nodded. ‘Lord of Hosts, our thanks to thee for this food. Bless this dwelling and those who pass their lives here. Amen.’

’You follow the old ways, Mr Shannow?’ asked Donna, passing a bowl of salt to the guest.

’Old? It is new to me, Fray Taybard. But, yes, it is older than any man knows and a mystery to this world of broken dreams.’

’Please do not call me Fray, it makes me feel ancient. You may call me Donna. This is my son, Eric.’

Shannow nodded towards Eric and smiled, but the boy looked away and continued to eat. The bearded stranger frightened him, though he was anxious not to show it. He glanced at the weapons hanging by the door.

’Are they hand pistols?’ he asked.

’Yes,’ said Shannow. ‘I have had them for seventeen years, but they are much older than that.’

’Do you make your own powder?’

’Yes, I have casts for the loads and several hundred brass caps.’

’Have you killed anyone with them?’

’Eric!’ snapped his mother. ‘That is no question to ask a guest - and certainly not at table.’

They finished the meal in silence and Shannow helped her clear away the dishes. At the back of the house was an indoor water pump, and together they cleaned the plates. Donna felt uncomfortable in the closeness of the pump-room and dropped a plate which shattered into a score of shards on the tiled wooden floor.

’Please do not be nervous,’ he said, kneeling to collect the broken pieces.

’I trust you, Mr Shannow. But I have been wrong before.’

’I shall sleep outside and be gone in the morning. Thank you for the meal.’

’No,’ she said, too hurriedly. ‘I mean - you can sleep in the comfort chair. Eric and I sleep in the back room.’

’And Mr Taybard?’

’Has been gone for ten days. I hope he will be back soon; I’m worried for him.’

’I could look for him, if you would like. He may have fallen from his horse.’

’He was driving our wagon. Stay and talk, Mr Shannow; it is so long since we had company. You can give us news of . . . where have you come from?’

’From the south and east, across the grass prairies. Before that I was at sea for two years - trading with the Ice Settlements beyond Volcano Rim.’

’That is said to be the edge of the world.’

’I think it is where Hell begins. You can see the fires lighting the horizon for a thousand miles.’

Donna eased past him into the main room. Eric was yawning and his mother ordered him to bed. He argued as all young people do, but finally obeyed her, leaving his bedroom door ajar.

Shannow lowered himself into the comfort chair, stretching his long legs out before the stove. His eyes burned with fatigue.

’Why do you wander, Mr Shannow?’ asked Donna, sitting on the goatskin rug in front of him.

’I am seeking a dream. A city on a hill.’

’I have heard of cities to the south.’

’They are settlements, though some of them are large. But no, my city has been around for much longer, it was built, destroyed and rebuilt thousands of years ago. It is called Jerusalem and there is a road leading to it - a black road, with glittering diamonds in the centre that shine in the night.’

’The Bible city?’

’The very same.’

’It is not about here, Mr Shannow. Why do you seek it?’

He smiled. ‘I have been asked that question many, many times and I cannot answer it. It is a need I carry - an obsession, if you will. When the earth toppled and the oceans swelled, all became chaos. Our history is lost to us and we no longer know from whence we come, nor where we are going. In Jerusalem there will be answers, and my soul will rest.’

’It is very dangerous to wander, Mr Shannow. Especially in the wild lands beyond Rivervale.’

The lands are not wild, Lady - at least, not for a man who knows their ways. Men are wild and they create the wild lands wherever they are. But I am a known man and I am rarely troubled.’

’Are you known as a war-maker?’

’I am known as a man war-makers should avoid.’

’You are playing with words.’

’No, I am a man who loves peace.’

’My husband was a man of peace.’

’Was?’

Donna opened the stove door and added several chunks of wood. She sat for some time staring into the flames, and Shannow did not disturb the silence. At last she looked up at him.

’My husband is dead,’ she said. ‘Murdered.’

’By Brigands?’

’No, by the Committee. They . . .’

’No!’ screamed Eric, standing in the bedroom doorway in his white cotton nightshirt. ‘It’s not true. He’s alive! He’s coming home - I know he’s coming home.’

Donna Taybard ran to her son, burying his weeping face against her breast. Then she led him back into the bedroom and Shannow was alone. He strolled into the night. The sky was without stars, but the moon shone bright through a break in the clouds. Shannow scratched his head, feeling the dust and grit on his scalp. He removed his woollen jerkin and undershirt and washed in a barrel of clear water, scrubbing the dirt from his hair.

Donna walked out to stand on the porch and watch him. His shoulders seemed unnaturally broad against the slim-ness of his waist and hips. Silently she moved away from the house to the stream at the bottom of the hill. Here she slipped out of her clothes and bathed in the moonlight, rubbing lemon mint leaves across her skin.

When she returned Jon Shannow was asleep in the comfort chair, his guns once more belted to his waist. She moved silently past him to her room and locked the door. As the key turned, Shannow opened his eyes and smiled.

Where to tomorrow, Shannow, he asked himself?

Where else?

Jerusalem.