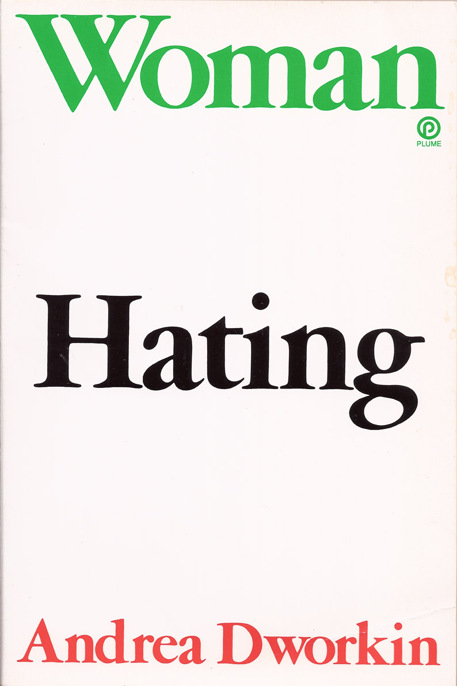

Woman Hating

PLUME

Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U. S. A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M4V 3B2

Penguin Books (N. Z. ) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

Published by Plume, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc.

10 9876543

Copyright © 1974 by Andrea Dworkin All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America Drawing on page 98 by Jean Holabird

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

BOOKS ARE AVAILABLE AT QUANTITY DISCOUNTS WHEN USED TO PROMOTE PRODUCTS OR SERVICES. FOR INFORMATION PLEASE WRITE TO PREMIUM MARKETING DIVISION, PENGUIN BOOKS USA INC., 375 HUDSON STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK IOOI4.

Permissions are on page 218

For Grace Paley

and in Memory of Emma Goldman

... Shakespeare had a sister; but do not look for her in Sir Sidney Lee’s life of the poet. She died young —alas, she never wrote a word.... Now my belief is that this poet who never wrote a word and was buried at the crossroads still lives. She lives in you and in me, and in many other women who are not here tonight, for they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed. But she lives; for great poets do not die; they are continuing presences; they need only the opportunity to walk among us in the flesh. This opportunity, as I think, it is now coming within your power to give her. For my belief is that if we live another century or so—I am talking of the common life which is the real life and not of the little separate lives which we live as individuals —and have five hundred a year each of us and rooms of our own; if we have the habit of freedom and the courage to write exactly what we think; if we escape a little from the common sitting-room and see human beings not always in their relation to each other but in relation to reality... if we face the fact, for it is a fact, that there is no arm to cling to, but that we go alone and that our relation is to the world of reality ... then the opportunity will come and the dead poet who was Shakespeare’s sister will put on the body which she has so often laid down. Drawing her life from the lives of the unknown who were her forerunners, as her brother did before her, she will be born. As for her coming without that preparation, without that effort on our part, without that determination that when she is born again she shall find it possible to live and write her poetry, that we cannot expect, for that would be impossible. But I maintain that she would come if we worked for her, and that so to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worthwhile.

Virginia Woolf,

A Room of One's Own

(1929)

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Ricki Abrams and I began writing this book together in Amsterdam, Holland, in December 1971. We worked long and hard and through a lot of living and then, for many reasons, our paths separated. Ricki went to Australia, then to India. I returned to Amerika. So the book, in its early pieces and fragments, became mine as the responsibility for finishing it became mine. I thank Ricki here for the work we did together, and the time we had together, and this book which came from that time and grew beyond it.

Andrea Dworkin

CONTENTS

Introduction 17

Part One: THE FAIRY TALES 29

Chapter 1 Onceuponatime: The Roles 34

Chapter 2 Onceuponatime: The Moral of the Story 47

Part Two: THE PORNOGRAPHY 51

Chapter 3 Woman as Victim: Story of O 55

Chapter 4 Woman as Victim: The Image 64

Chapter 5 Woman as Victim: Suck 75

Part Three: THE HERSTORY 91

Chapter 6 Gynocide: Chinese Footbinding 95

Chapter 7 Gynocide: The Witches 118

Part Four: ANDROGYNY 151

Chapter 8 Androgyny: The Mythological Model 155

Chapter 9 Androgyny: Androgyny, Fucking, and Community 174

Afterword 197

Notes 205

Bibliography 211

There is a misery of the body and a misery of the mind, and if the stars, whenever we looked at them, poured nectar into our mouths, and the grass became bread, we would still be sad. We live in a system that manufactures sorrow, spilling it out of its mill, the waters of sorrow, ocean, storm, and we drown down, dead, too soon.

... uprising is the reversal of the system, and revolution is the turning of tides.

Julian Beck,

The Life of the Theatre

The Revolution is not an event that takes two or three days, in which there is shooting and hanging. It is a long drawn out process in which new people are created, capable of renovating society so that the revolution does not replace one elite with another, but so that the revolution creates a new anti-authoritarian structure with anti-authoritarian people who in their turn re-organize the society so that it becomes a non-alienated human society, free from war, hunger, and exploitation.

Rudi Dutschke

March 7, 1968

You do not teach someone to count only up to eight. You do not say nine and ten and beyond do not exist. You give people everything or they are not able to count at all. There is a real revolution or none at all.

Pericles Korovessis, in an interview

in Liberation, June 1973

INTRODUCTION

This book is an action, a political action where revolution is the goal. It has no other purpose. It is not cerebral wisdom, or academic horseshit, or ideas carved in granite or destined for immortality. It is part of a process and its context is change. It is part of a planetary movement to restructure community forms and human consciousness so that people have power over their own lives, participate fully in community, live in dignity and freedom.

The commitment to ending male dominance as the fundamental psychological, political, and cultural reality of earth-lived life is the fundamental revolutionary commitment. It is a commitment to transformation of the self and transformation of the social reality on every level. The core of this book is an analysis of sexism (that system of male dominance), what it is, how it operates on us and in us. However, I do want to discuss briefly two problems, tangential to that analysis, but still crucial to the development of revolutionary program and consciousness. The first is the nature of the women’s movement as such, and the second has to do with the work of the writer.

Until the appearance of the brilliant anthology

Sisterhood Is Powerful

and Kate Millett’s extraordinary book

Sexual Politics, women did not think of themselves as oppressed people. Most women, it must be admitted, still do not. But the women’s movement as a radical liberation movement in Amerika can be dated from the appearance of those two books. We learn as we reclaim our herstory that there was a feminist movement which organized around the attainment of the vote for women. We learn that those feminists were also ardent abolitionists. Women “came out” as abolitionists —out of the closets, kitchens, and bedrooms; into public meetings, newspapers, and the streets. Two activist heroes of the abolitionist movement were Black women, Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, and they stand as prototypal revolutionary models.

Those early Amerikan feminists thought that suffrage was the key to participation in Amerikan democracy and that, free and enfranchised, the former slaves would in fact be free and enfranchised. Those women did not imagine that the vote would be effectively denied Blacks through literacy tests, property qualifications, and vigilante police action by white racists. Nor did they imagine the “separate but equal” doctrine and the uses to which it would be put.

Feminism and the struggle for Black liberation were parts of a compelling whole. That whole was called, ingenuously perhaps, the struggle for human rights. The fact is that consciousness, once experienced, cannot be denied. Once women experienced themselves as

activists

and began to understand the reality and meaning of oppression, they began to articulate a politically conscious feminism. Their focus, their concrete objective, was to attain suffrage for women.

The women’s movement formalized itself in 1848 at Seneca Falls when Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, both activist abolitionists, called a convention. That convention drafted

The Seneca Falls Declaration of Rights and Sentiments

which is to this day an outstanding feminist declaration.

In struggling for the vote, women developed many of the tactics which were used, almost a century later, in the Civil Rights Movement. In order to change laws, women had to violate them. In order to change convention, women had to violate it. The feminists (suffragettes) were militant political activists who used the tactics of civil disobedience to achieve their goals.

The struggle for the vote began officially with the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. It was not until August 26, 1920, that women were

given

the vote by the kindly male electorate. Women did not imagine that the vote would scarcely touch on, let alone transform, their own oppressive situations. Nor did they imagine that the “separate but equal” doctrine would develop as a tool of male dominance. Nor did they imagine the uses to which it would be put.

There have also been, always, individual feminists — women who violated the strictures of the female role, who challenged male supremacy, who fought for the right to work, or sexual freedom, or release from the bondage of the marriage contract. Those individuals were often eloquent when they spoke of the oppression they suffered as women in their own lives, but other women, properly trained to their roles, did not listen. Feminists, most often as individuals but sometimes in small militant groups, fought the system which oppressed them, analyzed it, were jailed, were ostracized, but there was no general recognition among women that they were oppressed.

In the last 5 or 6 years, that recognition has become more widespread among women. We have begun to understand the extraordinary violence that has been done to us, that is being done to us: how our minds are aborted in their development by sexist education; how our bodies are violated by oppressive grooming imperatives; how the police function against us in cases of rape and assault; how the media, schools, and churches conspire to deny us dignity and freedom; how the nuclear family and ritualized sexual behavior imprison us in roles and forms which are degrading to us. We developed consciousness-raising sessions to try to fathom the extraordinary extent of our despair, to try to search out the depth and boundaries of our internalized anger, to try to find strategies for freeing ourselves from oppressive relationships, from masochism and passivity, from our own lack of self-respect. There was both pain and ecstasy in this process. Women discovered each other, for truly no oppressed group had ever been so divided and conquered. Women began to deal with concrete oppressions: to become part of the economic process, to erase discriminatory laws, to gain control over our own lives and over our own bodies, to develop the concrete ability to survive on our own terms. Women also began to articulate structural analyses of sexist society — Millett did that with

Sexual Politics;

in

Vaginal Politics

Ellen Frankfort demonstrated the complex and deadly antiwoman biases of the medical establishment; in

Women and Madness

Dr. Phyllis Chesler showed that mental institutions are prisons for women who rebel against society’s well-defined female role.