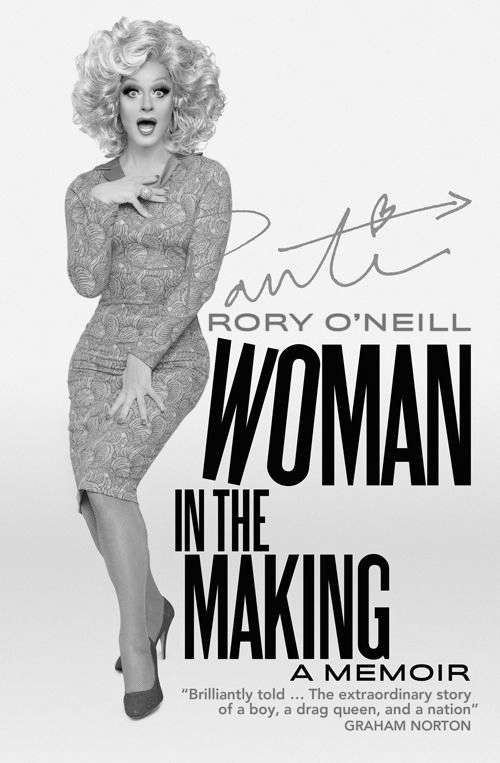

Woman in the Making: Panti's Memoir

Rory O’Neill is Panti Bliss, Ireland’s foremost ‘gender discombobulist’ and accidental activist.

Rory first began performing as his alter-ego Panti when he was an art student in the late ’80s before moving to Tokyo and becoming a fixture on the club scene there.

Returning to Dublin in 1995, Panti ran some of Dublin’s seminal club nights, hosted the legendary Alternative Miss Ireland for 18 years, and performed all over the world.

Panti has written and performed three critically acclaimed, hit theatre shows:

In These Shoes, All Dolled Up

and

A Woman in Progress

. In 2013,

All Dolled Up: Restitched

, a re-imagining of her three hit shows, had a sold out run at the Abbey Theatre and toured Australia. She is also the landlady of Pantibar.

Despite having no plans to wed, Panti’s creator is a champion of gay rights. Dressed with impeccable taste, done up to the nines, and wearing the best wigs money can buy, he has become synonymous with the campaign for equal marriage in Ireland. This is Rory O’Neill’s first book.

First published in Ireland in 2014 by

HACHETTE BOOKS IRELAND

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © Rory O’Neill 2014

The moral right of Rory O’Neill to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 44479 855 5

Hachette Books Ireland

8 Castlecourt Centre

Castleknock

Dublin 15, Ireland

A division of Hachette UK Ltd

338 Euston Road, London NW1 3BH

To my parents, Rory and Fin O’Neill, who always let

me be whomever I wanted to be

.

11: All Dressed Up and Somewhere To Go

12: A Big Disease With a Little Name

I

N

1979, I

STARTED

to think for myself.

It was the year that the Pope came to Ireland, but it was also the year that the eleven-year-old gay boy inside the (till then well-adjusted) eleven-year-old Mayo boy started to act up. These two things were not unrelated.

Looking back now, it seems almost inevitable that my gayness and my Catholicism were about to engage in their first bloody skirmish. After all, this was the year when the Irish chart’s top spot was wrestled from ‘Mary’s Boy Child’ by ‘YMCA’. But in Ballinrobe, County Mayo in 1979 we simply had no frame of reference for gayness. Gayness was Mr Humphries on

Are You Being Served?

but he lived in the strange, foreign world of TV, not in Ballinrobe.

We certainly did have a frame of reference for popes, though. Indeed, that reference wasn’t just framed, it was ornate gilt-framed, hung behind safety glass and expensive lighting.

And this pope was Irish. One of our own. Oh, sure, of course, he was from Poland –

and had a girl’s name –

‘Carol!’

‘He is

not

called Carol! His name is John Paul the Second!’

‘He is

now,

but before he was the Pope he was called Carol!’

‘Feck off you, Damien Fahey, he was not!’

– a country behind the heathen Iron Curtain, about which we knew nothing, yet we were absolutely sure it was just like Ireland because, like us, they were poor and, like us, they didn’t have swanky skyscrapers or Debbie Harry. So John Paul

the Second

would be welcomed with open arms and frantic bunting not just because he was the first pope ever to visit our proudly unswanky island (and long overdue too! Sure weren’t we only brilliant at being Catholic?) but because he was practically Irish. He even looked like one of us.

The Pope’s itinerary would take him round the country but, ostensibly, the reason for his trip was to visit the small Mayo village of Knock where they were celebrating the centenary of the appearance of the Blessed Virgin Mary herself in that otherwise unremarkable bog village. Knock is not far from Ballinrobe and it had already loomed large and holy in my Mayo childhood, but this was going to be Knock’s finest moment!

In truth, though, Knock is the world’s worst Marian shrine.

Have you ever been to Lourdes? I have. I was eighteen

years old, and a handsome, muscular Basque gypsy boy with black eyes, pregnant lips, sun-blackened skin and long blue-black hair that whipped in the hot breeze took me there in a beat-up old soft-top. I was in love and lust with him, and the drive through the dramatic Pyrenean mountains to the picturesque fairytale village of Lourdes formed the perfect backdrop to my mostly unrequited love. No one ever rode to Knock in a soft-top with a gypsy boy. For starters, you’d freeze to death. Even the apparition at glamorous picture-postcard Lourdes was so much better than at grey-fog-and-car-park Knock.

In Lourdes, the Virgin pulled out all the stops, all the big special effects – the sun was spinning, water was bubbling up from nowhere, and she kept reappearing to a very strict schedule, whispering very important secrets. In Knock she popped up once, in the middle of the night in the pelting rain, and ruined the drama by bringing a bunch of vaguely recognisable back-up saints. And possibly because of the weather she didn’t bring the

actual

Baby Jesus, she brought a lamb. Oh, c’mon, Mary! If you’re going to appear in a bog in the middle of the night you could at least bring the Baby Jesus and not a bloody metaphor. And the miracles are so much better in Lourdes! In Lourdes they have these stone baths fed with the icy water from the magic well (they always make such a big deal that no one has ever got an infection from the baths – as if not getting a verruca is somehow miraculous), and the walls of the bathhouse are covered

with the discarded crutches of the miraculously cured. It’s all very

dramatique

. In Knock, I think they have a pair of old reading glasses and a vague story of someone recovering quite quickly from the flu.

In Knock it’s all so literal, so grey. In Lourdes, there’s the charming grotto where holy water comes out of gold taps. In Knock, you’d fill your plastic Virgin bottles from aluminium push taps in the car park, and the apparition has been recreated in statue form in front of the pebbledash. (One of my secondary-school classmates, Eugene, claimed his mother had posed for the statue of the Virgin, and I chose to believe him because I thought that one day it would make a nice aside to this story. And I was right. Now when I see that statue of the Virgin I wonder what Eugene is up to these days.)

But now the Pope was coming and this wasn’t just going to be the greatest thing that had ever happened to Knock, it was going to be the greatest thing that had ever happened to Ireland! The Pope himself, this huge holy celebrity, was coming and nothing would ever be the same again. At least a million people would go to see him in the Phoenix Park, and at the youth mass in Galway, uncynical, unrebellious young people would gather in their hundreds of happy-clappy thousands to ‘Kumbaya, my Lord, kumbaya’.

There were no dissenting voices – or if there were, I was certainly too young to hear them. Everyone was on board.

Even I was on board. After all, I was already putting my latent drag tendencies to work as Ballinrobe’s pre-eminent altar (lady) boy. Indeed, my butter-wouldn’t-melt look, my theatrical sense of showy detail, and my onstage demeanour (pious, ostentatiously humble, but never pulling focus from the main players) meant I was much in demand for weddings (where I was handsomely rewarded in cash by the happy couple) and Easter services up in the Convent (where I was less handsomely rewarded by the soapy-smelling nuns).

But even my enthusiasm, driven as it was by the perceived glamour of the occasion, paled into insignificance beside my devout mother’s papal devotion. For days beforehand, our house, like every other house in Ballinrobe, was a hive of activity and nervous excitement, my mother a sandwich-making tweedy blur. At the crack of dawn on the big day she piled the Volkswagen high with egg sandwiches, brown bread, flasks of tea, ‘Pope stools’, Holy See flags, my sisters Edel and Clare, and me, and drove to the next town, Claremorris, where we parked in a field. (Claremorris is fifteen miles from Ballinrobe, and was Ballinrobe’s nemesis. They had a swimming pool and a railway station, and their school marching band had more stylish uniforms than ours, but we had a cattle mart, a one-way traffic system, water towers that looked like a pair of boobs, and our marching band just so happened to have won the Connaught regional title,

thank you very much, with no small help from a stylish turn on the glockenspiel by, yes, that’s right, Ballinrobe’s pre-eminent altar boy! Last Christmas my father picked me up from the station in Claremorris. After ten minutes I remarked that we still hadn’t managed to get out of the small rural town because of the traffic, and he spat, ‘Ah, sure it’s always shite in Claremorris. Those feckers have always thought they can just park anywhere they like. All over the road!’)

At Claremorris we boarded shuttle buses to the site at Knock, where we were herded into our assigned corrals. In the grey early-morning light it was a sight to behold – hundreds of thousands of damp pilgrims, their breath clouding the frigid air, muttering their bovine devotions, stretched out across endless moist fields, ironically vacated by their actual bovine residents for the glorious occasion.

Keeping us children close, my mother led the way (it was just our mother and us smaller kids – our older siblings would be going to see the Pope at the Youth Mass in Galway, and my father was somewhere among the glorious throng where he was working as a volunteer steward) till we set up camp miles from the stage, among nodding nuns, stressed mothers, praying shopkeepers, and farmers drinking cold tea from TK lemonade bottles, as an interminable tinny rosary bleated over the Tannoy system.