Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos (31 page)

Read Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos Online

Authors: Christine Halsall

9

. Williams, Kathlyn, part of an audio recording of wartime personnel at Hughenden Manor, by permission of the National Trust.

10

. Kodak Ltd London, Kodak Datasheet PP-2.

11

. Hughenden Manor, information sheet.

12

. Brachi (

née

Bohey), Joan, conversation.

13

. Williams, Kathlyn, audio recording.

14

. Horne (

née

Macalister), Elspeth, memoirs.

15

. Benjamin (

née

Bendon), Susan, memoirs.

16

. Williams, Kathlyn, audio recording.

17

. Duncan, Jane,

Letter from Reachfar

, p.65.

OST

S

ECRET

As Dorothy Garrod stared through the twin lenses of her stereoscope at images of a desert landscape, she must have recalled her days in Palestine some ten years previously when she had been searching for evidence of Neanderthal man. Now, in the autumn of 1942, she was searching the terrain of North Africa for signs of defences and obstructions that might impede the progress of an Allied amphibious invasion. Dorothy was working in a newly formed ‘Most Secret’ section at Medmenham called Combined Operations or ‘R2’. This section was to be permanently engaged on the production of PI reports required for future commando operations, and later on small operational landings in France and Belgium.

By this time America had entered the war, bringing with it much-needed armament and manpower resources. The desperate days of 1940 and 1941, when Britain stood alone against the Axis domination of Europe, had become a time when the Allies could plan for a return to the enemy-occupied countries of Europe, and ultimately to Germany itself. The first Anglo-American operation of the war was to be an invasion of North Africa, with the prime objective of seizing the French colonies of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, then controlled by Vichy France, and so to deny these territories to the German Afrika Korps under the command of Field Marshal Rommel. A rapid eastward advance through Tunisia would follow, enabling the Allies to push enemy forces towards a planned joint pincer movement with the British Eighth Army, pursuing Rommel’s troops westwards from Egypt. If successful it would push the German and Italian forces out of all the North African coastal countries for good and, with their departure, the Mediterranean Sea would be under Allied naval control, making the planned invasion of Sicily in 1943 an achievable objective.

The invasion of North Africa, code-named Operation Torch, was planned for 8 November 1942 under the leadership of US General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Time was short for all the preparations that had to be made and a huge amount of photographic intelligence material, essential for planning and briefing purposes, was needed. The numbers of special reconnaissance sorties immediately increased, intensive work was directed towards the production of maps and models of the area, and interpretation reports on enemy dispositions and defences were ongoing.

When ‘R2’ was formed at RAF Medmenham in August 1942, Douglas Kendall put together the small PI team responsible for producing most of this material. The team was inter-Allied and inter-service with representatives from all three services, including American and Canadian PIs. Head of section was Lieutenant Commander Philip Hayes, a very tall, fair-haired Royal Navy officer. Two PIs from Second Phase joined the team: Robert Bulmer, an architect in pre-war days and Robin Orr, an organist and composer at St John’s College, Cambridge. These two men had become very experienced in carrying out detailed interpretation of pinpoint locations used for landing agents on mainland Europe, and were to provide similar knowledge for Allied commandos seizing key ports and airfields in North Africa.

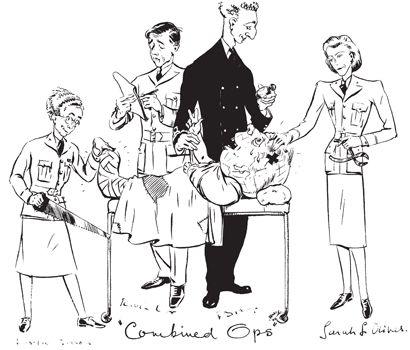

Cartoon of Combined Ops attempting to mend a broken world. While Lieutenant Commander Philip Hayes checks its condition and Robin Orr takes notes, Sarah Churchill applies a soothing hand and Dorothy Garrod prepares to remove an offending part.

Other members of the team included two Cambridge archaeologists, an actress and American and Canadian army PIs. The archaeologists were Peter Murray Threipland and Dorothy Garrod, both familiar with the patient searching necessary for examining the landing sites at Casablanca, Oran and Algiers. Terrain models were built by the Model-Making Section and the area reports produced by ‘R2’ showed the topography including details of roads, railways, ports, airfields and industries. Information on wireless telegraphy and direction-finding aerials, seen on air photographs, was aimed at the disruption or destruction of enemy communications. These reports were of considerable size and were fully illustrated, specifying every defensive aspect to be encountered.

Dorothy was described by friends as short and upright, wearing her thick, crisply wavy hair short. She was one of the two people at RAF Medmenham entitled to wear the General Service ribbon of the 1914–18 war on her tunic as she had been an ambulance driver in France for the last two years of that conflict. She gave an impression of controlled energy of mind and body, had a pleasant, quiet voice and even under pressure imparted an air of repose. In addition to her wartime experiences in France, she had travelled rough in remote places for archaeological digs in the 1920s. On her first dig in Palestine, her Arabic was fluent, her command absolute, and despite protests, she employed local women to dig the site because they worked harder than the men.

1

Glyn Daniel described Dorothy as easy to get on with: a generous, lovable, outgoing person who was interested in people. She enjoyed her work and the company of other staff at Medmenham, just as she had enjoyed the excavations before the war. Ann McKnight-Kauffer wrote:

Did you ever go to one of the parties Dorothy Garrod gave in her hut with peaches from her Cambridge garden in an old pie dish from the Mess and sprinkled over with a liqueur brandy given by Charlotte Bonham-Carter? We passed the dish round and dipped in our teaspoons and told more and more funny stories. The prime one concerned a dig in Turkey which was diverted to Albania and involved the requisitioning, by mistake, of the Lunatic Asylum.

2

The actress in the Combined Operations team was Sarah Churchill. In 2010 one of the Canadian army PIs on the team recalled her kindness:

When I was stationed at Medmenham they organized a big dinner and dance weekend and I arranged for my wife to join me. (I met the love of my life on 28th June 1941 at the Palais de Dance in Kingston-on-Thames and we were married on 22nd August 1942 in Kingston.) Jean arrived by train on Friday evening but in her rush to greet me, left her suitcase on the train. It was never recovered and you can imagine our embarrassment arriving to check in at the Compleat Angler in Henley sans luggage! However, despite raised eyebrows, we managed. I informed Sarah of our predicament and she met us at the door of Medmenham and took Jean under her wing making her feel at home despite the loss of her best dress and high heels – impossible to replace in those times. Sarah was a great lady and did not deserve her later experiences.

3

By the evening of 7 November 1942 the intense work and rush at Medmenham for Operation Torch was over and Sarah had 48 hours’ leave to visit her parents:

Chequers was near enough for me to go over on my leaves. Sometimes, I would go on a borrowed army motorcycle – so heavy that I had to have a hand to get me started. Luckily, there were regular van deliveries between the three RAF stations in the area and I could hitchhike most of the way to Chequers. On arrival, I would normally go straight up to see my father as, being in uniform, I did not have to dress for dinner. On one special occasion he was in his bath, floating full length with an enormous sponge strategically placed.

‘Come in, come in. What have you been up to?’

‘Just the usual routine.’

‘Ah.’

He yelled for Sawyers, his valet, who wrapped him in an enormous Turkish towel. I waited discreetly while drying and dressing occurred. Then came the final touch, combing his hair and then brushing it with two ivory hair brushes. He used to part the two or three remaining hairs across the dome of his head with meticulous care, splash on some cologne and then we would go down to dinner.

On this particular evening, while this elaborate hair-dressing procedure was taking place, he said, ‘At this very moment, sliding stealthily through the Straits of Gibraltar under cover of darkness, go 542 ships, for the landings in North Africa.’

I couldn’t resist it. I said, ‘543.’

‘How do you know?’

‘I’ve been working on it for three months.’

‘Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘I believe there is such a thing as security.’

He looked at me with what I feared would be a blaze of anger at my impudence. Instead, he chuckled, and we went down to dinner where he told the story delightedly. Later, when Mrs Roosevelt came over to England to see how women were faring in the services, my father proudly repeated the story to her. Mrs Roosevelt, a remarkable woman of whom I became very fond, returned to America to give her account of English women’s work in the war machine and she recounted this story to illustrate the importance of security, even between father and daughter. It went down very well, I am told, but not for me. I was summoned to the Air Ministry for a carpeting for breach of security!

4

The landings on the North African beaches were successfully carried out, French resistance minimal, and after consolidating their forces the Allies moved into Tunisia. General Montgomery’s success at El Alamein forced the Afrika Korps to retreat westwards and, after fierce fighting, it was eventually trapped between the Eighth Army and the Allied troops in Tunisia. With the Afrika Korps’ surrender, a major step had been taken towards the Allies’ return to the European continent.

Mention has been made of terrain models being built as part of the preparations for Operation Torch. For centuries, detailed models, built to scale and showing fortifications and features of the landscape, had supported military operations. Early in 1940 a model-making workshop was formed at the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough after representatives of the army, navy and RAF met to discuss intelligence gathering for commando raids. The three-dimensional models, built to precise scale and detail, were invaluable when briefing troops prior to an operation; they could inspect the terrain, landmarks and obstacles they would encounter so they became familiar and ‘fixed’ in their mind’s eye.

The Model-Making Section, ‘V’, moved to Medmenham in 1941, setting up their workshops in the stables off one of the courtyards. A number of suitable recruits had to be quickly found as very few professional model makers, who were normally employed by architectural or legal firms, were available. Craftsmen recently called up for war service in the RAF suddenly found themselves transferred to model making, while more candidates were found among the staff and students in art schools. The result of this targeted recruitment drive was the creation of a unique collection of highly talented artists, sculptors, engravers, illustrators and others who formed the core of the model makers. As the value of the models was recognised, it was not long before more model makers were desperately needed. Earlier manpower sources had run dry so the suggestion was made: ‘Well then, what about woman-power?’ After the establishment shockwaves had receded, the recruiters set off to find suitable female model makers from other sections and in art schools; the first two to arrive at Medmenham were Thea Turner and Gilly Porter. Only WAAF personnel were recruited for this work and their numbers were never large, amounting to a total of two officers and twenty-one other ranks.