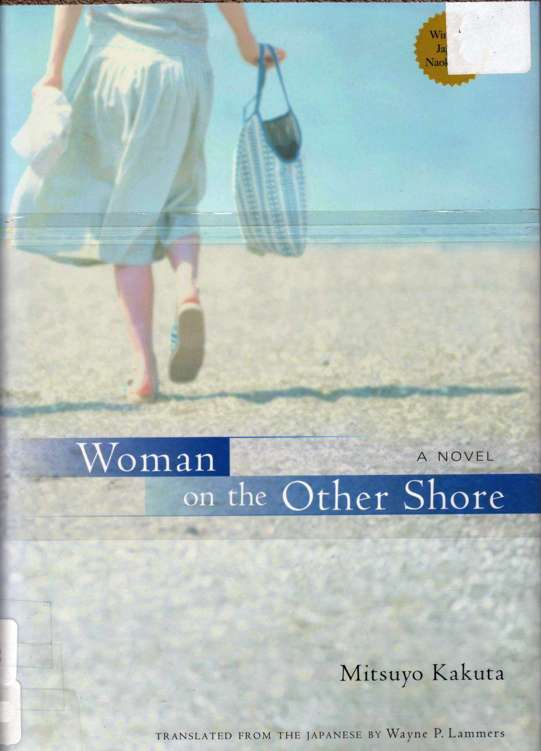

Women On the Other Shore

Read Women On the Other Shore Online

Authors: Mitsuyo Kakuta

Woman on the Other Shore

Mitsuyo Kakuta

Translated by Wayne P. Lammers

Woman on the Other Shore

This book has heen selected by the Japanese Literature Publishing Project (JUT), which is run by the Japanese Literature Publishing and Promotion Center (J-Lit Center) on behalf of the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan.

Originally published in Japanese in 2004 by Hungei Shunju, Tokyo, under the title

Talgan no kanojo,

I )istributed in the United States by Kodansha America, Inc., and in the United Kingdom and continental Kurope by Kodansha Kuropc Ltd.

Published by Kodansha International Ltd., 17-14 Otowa 1-chomc, Bunkyoku, lokyo 112-8652, and Kodansha America, Inc.

Copyright © 2004 by Mitsuyo Kakuta.

English translation copyright © 2007 by Wayne P Lammers.

All rights reserved. Printed in Japan.

First edition, 2007

15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kakuta. Mitsuyo, 1967-

[Taigan no kanojo. English]

Worn an on the other shore / Mitsuyo Kakuta ; translated by Wayne P. Lammers.

p. cm.

"Originally published in Japanese in 2004 by Bungei Shunju, Tokyo, under the title: Iaigan no kanojo"—T.p. verso.

ISBN-13: 978-4-7700-3043-6

1. Lammers, Wayne P., 1951- II. Title.

PL855.A3T35I3 2007

895,6'36—dc22

2007001381

When am I ever going to stop being the same old me?

With a start, Sayoko Tamura realized she'd been absentmindedly turning the same question over and over in her mind, and a crooked smile came to her lips. T h e very fact that she was thinking such thoughts meant one thing hadn't changed since she was a little girl. She'd spent practically her entire childhood wondering what it would be like if she were somebody else.

What if I were everybody's

sweetheart Yoko? What if I were super-whiz Nitta?

Sitting on a park bench under a canopy of tree branches, she turned her gaze toward her three-year-old daughter playing in the sandbox. T h e r e were many children Akari's age at the park, and they had all found at least one or two other kids to play with. But as usual Akari was shoveling all by herself off in the corner. When she got to be a little older, would she be asking herself the same question:

What if I were somebody else?

With a sigh, Sayoko pulled her cell phone from the hip pocket of her jeans. T h e log showed no missed calls, so she dialed her home phone to check for messages there. Nothing. The call she was expecting had not yet come.

Akari had been born three years ago in February. About six months later, Sayoko followed the advice of the parenting magazines she read and began taking her daughter on outings to the park closest to home—at the suggested hour, and dressed according to form. She got to know other mothers with children Akari's age, and even arranged to meet with them to go for their babies'

7

periodic checkups and vaccinations together. But as time passed Sayoko began to notice a certain cliquishness among some of the young mothers who came to the park. She saw that they were following the lead of one woman in particular, and although they were careful not to be too open about it, avoiding any obvious snubs, they were in effect ostracizing one of the other mothers. Being over thirty herself, Sayoko was noticeably more advanced in age than most of the women, so she could accept that they might think she didn't fit in. It didn't mean they thought she was a bad person. They would naturally assume that someone as much older as she was would have different perspectives and be harder to open up to. It was an entirely understandable response, really.

Even so, once she realized what was going on, Sayoko found it depressing to go to the park, and she gave up the daily outings for a while. But then it wasn't long before she started feeling guilty about keeping her daughter cooped up at home all the time. She worried that without the park and its opportunities for meeting other children, her little girl might never develop the social skills she needed.

And so Sayoko and Akari had spent the last two years slowly making the rounds of every park within walking distance of their condominium. Once they'd been going to Park A long enough for Sayoko to identify the social dynamics of the mothers who gathered there, they moved on to Park B. Fortunately, there was no shortage of parks large and small within range of their building.

Sayoko learned that people who wandered from park to park this way were known as "park hoppers."

But it's not like we're hopping

around by choice,

she muttered as if making excuses to someone as she left the house with Akari in search of each new park.

We're just

trying to find a park where we can feel at home.

This particular park, about a twenty-minute walk from their building, was the largest they'd found in their travels, and it drew a more mixed crowd t h a n t h e c o m m u n i t i e s of young mothers Sayoko had found so characteristic of t h e smaller parks. Here she saw fathers walking their babies, or older folks playing with their grandchildren, and even t h e m o t h e r s w e r e m u c h more varied in age and dress. Not only that, but, as a m a t t e r of courtesy, all the grownups ignored each other; nobody ever tried to talk to anyone unless it was absolutely necessary. D e c i d i n g she preferred it that way, Sayoko had been bringing h e r d a u g h t e r h e r e for nearly six months now.

Of course, e v e n if t h e grownups kept to themselves, the little ones usually m a d e friends. While their parents buried their noses in books or fiddled w i t h c a m e r a s nearby, the children thrown together in the midst of all t h e play equipment gradually gravitated toward one another a n d b e g a n playing with kids they'd never seen before.

Now and again tears would flow in a dispute over a toy, but even then the grownups tried h a r d not to get involved. It seemed to be an unwritten rule at this park.

Digging in t h e s a n d w i t h her plastic shovel, Akari paused to watch two girls her age playing h o u s e in the middle of the large sandbox.

One of t h e m wore a red T-shirt, t h e other a sunflower-print dress, and they were giggling a n d chattering over a set of colorful plastic dishes, their voices ringing crisply into the air. A little boy tottered up from t h e far side of t h e sandbox and eyed them as if wanting to be included. At first t h e y just stared back, but then the girl in the sunflower print picked up a fork and handed it to him, affecting what must have b e e n t h e mannerisms of her own mother.

While pretending n o t to watch, Sayoko kept a surreptitious eye on the threesome in t h e middle of the sandbox and on Akari shoveling all by herself in o n e corner. Every so often she saw her daughter cast a glance toward t h e others, t h e n quickly go back to her digging.

Sayoko often marveled at how much the daughter took after the mother. No matter h o w badly t h e girl wanted to join a game, she was too shy to simply walk up and ask if she could play, so she waited timidly nearby, hoping to be invited. Of course, children seldom noticed such things, and by the time Akari cast her next sidelong glance the others might have run off to play somewhere else. As Sayoko watched Akari's eyes dart back and forth, she invariably recognized in them the movements of her own eyes. This was exactly how she'd looked at the mothers in all those other parks, where she'd found it so hard to fit in. And each time she realized this, it gave her a deep sense of failure as a mother. If only she were a more self-confident and outgoing parent who could strike up easy conversations with whomever she met, pretending not to notice the walls that cliques tried to erect, then surely Akari would be growing into a more self-confident and outgoing child as well.

Sayoko had considered going back to work before this. She'd thought about it during the first two years of her marriage, before Akari was born, as well as in the three years since. Instead of fretting all the time about which park to go to, maybe what she needed was to find herself a job and put Akari in nursery school. Her daughter was bound to make more friends there than she made as a "park hopper." She would probably learn to be more sociable. Yet Sayoko had continued to hesitate.

What kind of mother chooses to work when

her child's at such a precious age? The poor girl, being torn away from

her mom like that!

She made excuses for her inaction by repeating the refrains she'd heard from other stay-at-home mothers at the park. But the real reason for dragging her feet lay elsewhere. When she saw cliques forming among the young women at the parks, it reminded her all too well of the office politics she'd had her fill of before she got married.

After college, Sayoko had taken a job with a film distributor, a company known for giving new hires a great deal of freedom and responsibility from day one. She enjoyed the work itself, and she also liked the easygoing company culture in which subordinates weren't expected to be so formal with their superiors. But as the years went by, tensions t h a t h a d b e e n indiscernible at first rose to the surface.

Certain m e m b e r s of t h e p e r m a n e n t female staff were caught in an endless cycle of p e t t y charges and counter-charges with the contract workers—about w h o was supposed to make sure coffee and iced tea were available; about what time workers could leave at the end of the day; about t h e dress code; about personalizing the ladies' room.

If you tried to stay out of t h e fray, whether by being nice to everyone or ignoring everyone, you could soon find yourself being picked on by b o t h sides. It required a tremendous effort to maintain the right distance f r o m t h e opposing parties, and in fact Sayoko expended huge a m o u n t s of energy attempting to do exactly that. Fortunately, just w h e n she was b e c o m i n g completely fed up with the toll this was taking, h e r boyfriend, Shuji Tamura, conveniently popped the question. She quickly said yes, a n d almost as quickly submitted her resignation to t h e company. Shuji was obviously none too happy about the latter—he h a d assumed Sayoko would continue working even after she got m a r r i e d — b u t she pretended not to notice.

It was a b o u t a m o n t h ago t h a t Sayoko had finally broached the subject with h e r h u s b a n d .

"I've b e e n t h i n k i n g I'd like to go back to work."

"Sure, why not?" he replied absently, not even bothering to ask what might have p r o m p t e d h e r decision. Sayoko realized he must think she wasn't serious, she was just sounding out a momentary whim.

But Sayoko was dead serious. She bought recruitment magazines and s c a n n e d t h e job listings, looking for anything that said No

experience necessary. Homemakers welcome.

She'd gone to a number of interviews a n d b e e n t u r n e d down every time, for whatever reason.

For each a p p o i n t m e n t , she had to leave Akari with her mother-in-law, w h o invariably h a d a snide remark or two to offer. But Sayoko refused to let t h e repeated jabs get to her; if anything, she became more d e t e r m i n e d t h a n ever as she searched the ads and sent in applications.

Now she glanced at the display one last time before shoving the phone back into her hip pocket. She leaned her head back and looked up at the sky. Beyond the leaves swaying gently overhead stretched a flawless expanse of cerulean blue.

The woman she'd interviewed with two days before had told her she'd get back to her today. Despite her perfect string of rejections so far, Sayoko hoped this time might be different. In fact, she was secretly counting on it. Not only was the woman Sayoko's own age, but they'd gone to the same school. Since it was a megaversity with a huge student body, it wasn't actually all that unusual to run into fellow alumni, but this woman behaved as if she'd found a long lost friend.

"Can you believe it?" she beamed, sounding very much like she was still a student. "Just think how many times we must've walked right past each other! Under the ginkgo trees coming in from the gate, you know, or in one of the dining halls."