Work Clean (17 page)

Authors: Dan Charnas

This

sounds

complicated, but my son grasped this principle by the time he was 5 years old.

“Daddy,” he said one day on the subway platform, pulling my arm toward a set of benches. “Stand over here.” Why the benches? Because he knew, like most New Yorkers do, exactly where to exit on the platform at our destination station. And why do New Yorkers memorize that? So that when we get to our destination, we reach the staircase before it gets blocked by a crowd of people. At 5, he knew that he could

redeem

the time we spent waiting at our origin in order to

minimize

the time we spent waiting at our destination. That's a combination of balanced movement, making first moves, and finishing actions. That's mise-en-place!

Perfectionism comes from either of two emotional sources: fear of failure, or despair over its impending arrival. And there are two kinds of perfectionists: those who quit their projects, and those who keep working on them forever. Both are afraid, but the former copes by stopping work, and the latter by working indefinitely.

Remember:

Striving for perfection

and

perfectionism

aren't the same thing

.

Both the striver and the perfectionist aim toward an ideal. But the striver knows that excellence is not about

creating

something of the highest quality; it's

delivering

something of the highest quality, with all the constraints that delivery entailsâdeadlines, expectations, contingencies, feedback. The chef cannot tinker forever with a dish: Customers get hungry. Food spoils. The chef

must deliver.

In our society we've come to see speed and urgency as antithetical to quality. For the chef, the deadline is

integral

to quality. Without delivery, there's no feedback, severing the improvement loop that creates excellence.

Excellence is quality delivered.

Deadlines compel excellence. Lorne Michaels, who has been delivering 90 minutes of influential TV comedy for more than 40 years with

Saturday Night Live,

has said: “We don't go on because we're ready. We go on because it's 11:30.” And while

SNL

has produced plenty of less than perfect moments, a comedy sketch

still needs to be ready by 11:30 p.m. to have a chance to be perfect. Don't let perfectionism make you miss

your

moment.

Try to break large projects into chunks that are finishable in the time you allot for them. Set benchmarks. For example, I know I can usually write 500 words in 1 to 2 hours. So I break writing projects down into chunks of that size, and try not to assign myself more than that amount so I can actually finish what I've started. Smaller goals lift the spirits because they make it easier for us to see the end. To recap:

1.

Figure out the discrete parts of each project.

2.

Build your pause points with intentionality.

3.

Work intently toward those points.

When so many of us beg the Universe for a chance to

just get some work done,

why is it that when that time finally arrives, we often do anything we can to

escape

it?

Here's why: The process tasks we complain about are often easier to do than immersive work, and we get a little endorphin rush every time we deliver on one of those process tasks. Immersive work is harder. It doesn't yield those little rushes as often. Because it's creative and thus a reflection of ourselves, it puts our own demands and emotions front and center. Is it any wonder, then, why we abandon our creative work to chat on social media or browse the Internet?

Creativityâwhat we do when our hands are shaping something, whether words or numbers or designs or images or musicâisn't linear. Booking yourself into some immersive time and then treating it like a 2-hour prison to attempt to squeeze every second out of it is a huge mistake. Our creative sessions need to breathe, as we do. We need mental, physical, and social breaks. Working clean

with obligations and expectations means that we should strive to make breaks

intentional

ones.

The rules:

1.

Any time you enter a creative session,

take as many breaks as you like

within it.

2.

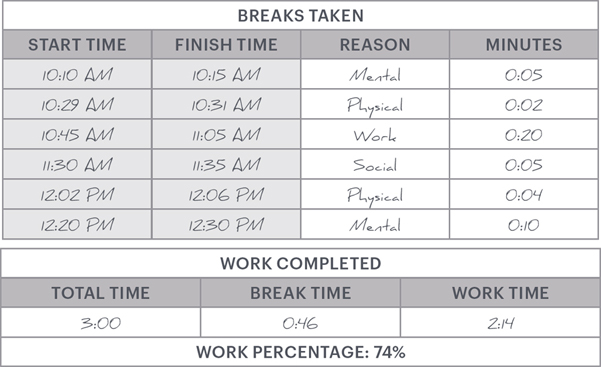

On a piece of paper or a spreadsheet, begin an

intentional break

log.

3.

At the top, write down your start time.

4.

For each break, log your in and out times on a new line.

5.

Beside each break, put the reason for the break.

â

Mental (e.g., when you want to chat, browse, or when you just can't think)

â

Physical (e.g., bathroom breaks, snack breaks, stretching, or walking around)

â

Social (e.g., interruptions, chats with friends or colleagues)

â

Work (e.g., other projects)

Time in: 10:00 AM

Time out: 1:00 PM

6.

When you are finished with your creative session, log your end time.

7.

Calculate the time between your start and end times, and subtract the amount of time you took for breaks.

You could also use a time-tracker app for this habit. For my own creative sessions, I've created a spreadsheet that automatically calculates the percentage of my time I've spent working within that session. And I know that if my number is below 75 percent, the session has been a difficult one.

The point is

not

to get that percentage up! The point is that we understand

why

and

when

we need breaks, so we can better know how to schedule and encourage our creative process.

When Charlene Johnson-Hadley left the restaurant each evening, she returned to a home teeming with her 11-year-old daughter Chloe's colorful art projectsâpaintings, drawings, sculpturesâall of them unfinished.

Charlene's training as a chef made Chloe's creative process difficult to watch. For each of these objects, Chloe had a plan, yet another addition or improvement she was going to make. But the incomplete projects only seemed to accumulate. Finally, in a quiet moment, Charlene decided to say something.

“Chloe, you are a very smart girl, but you have a problem focusing.”

“I know, Mommy,” Chloe replied. Charlene's jaw dropped.

“But,” Chloe continued, “sometimes I have to do more than one thing at a time.”

“That's fine,” Charlene replied. “There are times you have to multitask. But you can't start five things and then have five things not finished. You can't have 70 percent done, 80 percent done, 20 percent done, 30 percent done, 90 percent done. Even 90 percent finished is still unfinished. So if you need to do more than one thing at a time, do two things, and don't go on to that third thing until you're done. If you do that, by the time you're 14, you'll be able to do five things and then you will complete them. The key is completing.”

Charlene watched Chloe, hoping she'd take it in. If Chloe could deliver, she'd have a powerful life skill. She might not be a chef like her mommy, but she'd be the chef of her own life.

A few months later summer came. On the morning of her Brooklyn neighborhood's annual block party, Charlene walked outside and saw Chloe, who had set up a table on which she displayed a number of finished paintings. Beside them she had written a price list with a Sharpie. Chloe had done it all by herself.

She sold all her pieces by the end of the day.

Recipe for Success

Commit to delivering. When a task is nearly done, finish it. Always be unblocking.

SLOWING DOWN TO SPEED UP

A chef's story: The base runner

Angelo Sosa, center fielder for his high school baseball team, the Xavier Falcons, looked for a head start. He was halfway between second and third base before the opposing pitcher noticed, and Sosa tagged third milliseconds before the ball hit the third baseman's glove. Sosa stole a lot of bases.

Sosa, while shy in social situations, competed fiercely on the field. His fatherâa Dominican US Army captain-turned-psychiatristâran Angelo and his six siblings like a troop around their rural Connecticut home and corrected them with a hard hand. When Angelo did his chores, he ran. When he left home, he kept running.

After high schoolâwhen he had traded his pro baseball aspirations for a culinary careerâSosa spent his first days at the CIA like, he says, a dubiously trained rookie cop looking for action: trying out for the school's Olympic team and demanding a meeting with the president of the college, Ferdinand Metz.

Metz's assistant stared at the first-year student. “The only time students meet with Dr. Metz is at graduation,” she sniffed. Sosa persisted. One morning he found himself on the doorstep of President Metz's campus residence. What was Sosa so desperate to say?

“President Metz, I'm Angelo Sosa. I want you to remember my

name, because I'm going to be one of the most famous chefs in the world. Thank you for your time.”

Sosa graduated from the CIA with a fellowship that propelled him into the kitchens of Christian Bertrand, where he rose to sous-chef. After 3 years, in 1999, Bertrand asked Sosa if he'd like to meet the one chef whom every young culinarian in New York seemed to want to work for: Jean-Georges Vongerichten, who had just opened his latest four-star restaurant, Jean Georges, in a hotel off Central Park.

Sosa remembers that meeting in a corona of white: gleaming ivory-colored tiles in a spotless kitchen; Jean-Georges himself in his white chef's jacket, reading the

New York Times.

When Vongerichten spoke, Sosa understood only half of what he said, but the chef's voice sounded like liquid silver. Jean-Georges motioned for Sosa to come with him, leading the young apprentice to a new Bonnet oven from France as if showing him a Ferrari, placing Sosa's fingers on the handle so that he could feel the weight of the door. Jean-Georges smiled.

You see?

Sosa, blinded by the light, accepted the chef's offer of $6.25 an hour to take a demotion to the entremetier station. Sosa floated all the way to Grand Central Terminal. Only at the end of his commute to Stanford, Connecticut, did Sosa realize he would now make less than half of his current salary; and that his new weekly paycheck would barely cover his monthly Metro North train pass, let alone his rent. Sosa debarked, walked past his house and into a nearby bank, and talked his way out of there with a loan for $13,000 to fund his shortfall.

Later that week, Sosa asked to speak with Jean-Georges. “This is the biggest investment of my life,” Sosa informed him. “And I want you to know that I'm going to be the best chef who has ever worked for you.” Jean-Georges bumped him up to $12 an hour just for having the balls.

Back when he played baseball, Sosa figured he could make it to the minors. Now here he was, in the majors of a different league. As he had both on the field and in previous kitchens, Sosa relied on speed for advantage. He fancied himself a martial artist, a ninja, exploding on his station and leaving others dazzled.

Except they weren't.

Vongerichten liked to put his cooks in the shit; he'd drop a new lunch menu 1 hour before service just to watch his brigade scramble. Sosa ran, but in his mad dash, he got sloppy. Much of what he cooked did not meet Vongerichten's or his sous-chef Jacques Qualin's exacting standards. He forgot simple things, like seasoning the water in which he blanched asparagus.

Throw it out, do it again.

He cut his vegetables in inconsistent widths.

Throw it out, do it again.

He panicked, and panic made him rush even more. The more he rushed, the more he fell behind. The more he fell behind, the more hell he caught.

The crew began to tease him. Josh “Shorty” Eden gave Angelo a nickname:

Hurry-Up-and-Make-It-Twice Sosa.

Qualin would toss Sosa's mise-en-place every evening. Sosa started coming in earlier in the morning, sometimes sleeping in his uniform, when he could sleep at all, trying to regain that head start. One day during service, after Qualin reamed him for another underseasoned dish, Sosa's entremetier partner piled on:

Your station is shit, dude. You don't even deserve to be here. You are the worst partner.

That's it,

Sosa thought. In rage and frustration, he ran through the kitchen, past the coffee station, toward the door. His wallet and street clothes were still in the locker room behind him.

Fuck it

, Sosa thought. The wallet was empty anyway. But right below that red exit sign, Sosa felt as if he had walked into an invisible wall. He couldn't leave. Instead, he walked back to his station, grabbed his partner, and said: “Don't ever fuck with me again.”

The mere act of talking tough ended Sosa's hazing period, which in turn relaxed him. As he relaxed, he began to behave in a way that didn't come naturally to him: He slowed down. As he slowed down, he made fewer mistakes. As he made fewer mistakes, he regained the finesse he needed to compete in the kitchen of Jean Georges. Sosa acquired what he refers to as

equilibrium

âan elegant balance of speed and refinement. Now his movements

were

becoming ninja-worthy: less lurching, more smooth. When he caught a mistake, he didn't panic. If he didn't cut the carrots correctly, Sosa stopped, took a breath, cleaned up, and began again, cutting them to perfection.