Work Clean (6 page)

Authors: Dan Charnas

“What a waste,” Stephen said, as if reading Jeremy's mind. “How much did this cost us?”

Stephen walked out of the door, leaving Jeremy. “Get it done,” he heard Stephen say.

Jeremy felt his phone ringing. He pulled it out of his pocket. 6:00 p.m. His wife calling.

Adam's soccer game!

Jeremy was about to have one more difficult conversation in a day that already had more of them than he could remember.

He hoped tomorrow would be a better day.

Jeremy's story is familiar to those of us who work in offices. Perhaps we haven't had

one

day go

so

wrong, but most people who make a living with words, images, and numbers struggle with overwhelming workload and communication and make many of the same errors.

Jeremy's problem isn't poor character. His intentions are honorable: to be a good husband and father, to provide for his family, to succeed at his new job, to create an excellent product, to work hard, to please his boss and honor his colleagues. At work, he's generous to a fault: helping his coworkers even when it takes time away from his own tasks and being cordial to the receptionist when he's within his rights to request some different behavior from her.

His problem isn't work ethic. Jeremy works at a furious pace. He doesn't “steal” time from the company by gossiping or playing video games or browsing social media at his desk. If anything, he's stealing time from himself when he shortens his lunch break. Even his distractedness in meetings comes from a desire to be working.

His problem isn't self-discipline. He does have the will and ability to focus.

His problem isn't lack of skill. He knows how to create great Web sites and visual presentations; it's why his boss hired him in the first place.

Jeremy's problem is this: He doesn't have a

philosophy

and a

system

that will help him do all the other things he does. He has the requisite skills to work; he just doesn't know how to handle a

workload.

Jeremy spent tens of thousands of dollars in tuition to understand art, design, and language. He spent years acquiring knowledge of code and the workings of the Internet, and experience in testing his ideas. But his formal education never included instruction on how to organize and conduct his

workflow;

and by the time he was a professional, there were few opportunities or incentives to learn. He has inner discipline to work longer and harder, but he doesn't follow an outer disciplineâa body of principles and behaviorsâto guide his considerable will and skill. As a result, Jeremy can't execute the work he's trained to do. He gets frustrated and panics, and he's not great at handling those emotions. So he makes mistakes that jeopardize his business and says things that damage his relationships.

Like Jeremy, we may have a personal abundance of talent, energy, and resources. But we remain overwhelmed by the amount of work we have to do, and a big part of our being overwhelmed comes because we have never been taught how to

manage

that work. Even doctors and lawyers confide that they didn't learn many of the essentials of their professions in school. Near the top of that list for them, and for us, is how to prepare, how to create order, and how to prioritize the work at hand.

Almost all modern work requires personal organization. And yet, as in the other half of our livesâpersonal relationshipsâlittle comprehensive training exists. We enter into the chaos of both arenas of our adult lives with minimal counsel and are expected to wing it. At least when we falter in our relationships, psychotherapists are there to help us pick up the pieces. When we get reprimanded on the job or fired, we're pretty much on our own. In the absence of a formal education in organization, we've had to help ourselves.

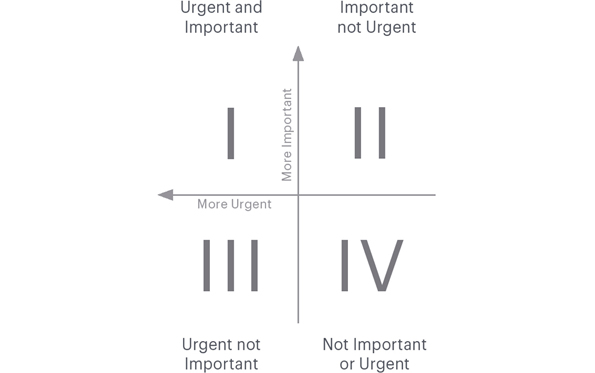

“I have two kinds of problems: the urgent and the important,” President Dwight D. Eisenhower said in 1954, quoting an unnamed college president. In his speech, Eisenhower pointed to what he called a dilemma of modern man: “The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent.”

Eisenhower's wisdom was years ahead of its time at the dawn of the corporate era; the tides of personal organization products and literature wouldn't begin coming in until the 1980s and 1990s. Eisenhower's ideas appeared in the writings of the first big productivity and time-management guru, Stephen R. Covey. Beginning in 1989, millions of people bought Covey's book

The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People

, which outlined a principle-centered approach to order and organization. Covey argued that the pressure of our daily tasks diminishes when we consider the bigger picture of our life and legacy. His 1994 book,

First Things First,

repurposed Eisenhower's ideas as a matrix into which tasks could be sorted and executed, with the “Important” and “Urgent” on two separate, intersecting axes, thus creating four “boxes,” or “quadrants.” Covey urged his readers to

escape the culture of urgency and do important things first.

In 2001, David Allen's book

Getting Things Done

offered one of the most comprehensive systems yet for managing daily work and introduced a powerful concept for prioritizing: In all projects, keep a focus on the “next action.” By the turn of the millennium, both Covey and Allen had created huge training businesses, salvation systems serving corporations and individuals who couldn't get that kind of education elsewhere.

All told, Americans spend more than $10 billion a year on self-help products, including organization books, tools, seminars, and software. The digital age was supposed to quicken our pace and lighten our load but it has largely done the opposite. The benefits of the tools that allow us to work faster have been overshadowed by the distractions of an Internet-driven information deluge, by the temptation to multitask, and by the increasing workloads brought on by job consolidation. Now we need to be saved from our digital devices as well. Web sites on “lifehacking” abound with the latest ideas and concepts in organization. We are drowning in salvation.

What most of these techniques lack is a holistic approach. One strategy is not a complete

system.

A great method for arranging our space, for example, may not include guidance for organizing our time. And even a comprehensive system may not take into account the person who has to make that system work. Organization doesn't entail only manipulating objects around usâwhere things go and how tasks should be handledâit needs to deal with our internal environment as well. Organizing is not an intellectual exercise. We must also know how to handle the mental, emotional, and physical challenges and resistance we all encounter. In other words, we don't just need strategies and systems. We also suffer for the lack of guiding principles that account for all our human dimensions.

Such a set of principles exists. It is a body of knowledge that carries the heft of history and the benefits of widespread practice. It is mise-en-place.

The Zen-like work habits of so-called blue-collar cooks in the best kitchens stand in stark contrast to the wastefulness of the white-

collar world of messy desks, endless meetings, bottomless e-mail chains, and general half-assedness that plagues even the best of companies.

But is it fair to compare the kitchen to the office?

The kitchen and office share some qualities. Workers in both places must contend with a deluge of tasks under tremendous deadline pressure and often inadequate resources. In both environments, workers face a constant stream of inputs and requests, too little time to process them, and many tasks demanding simultaneous attention.

But, as chefs will tell you, the kitchen is a world apart from the office. Kitchens are places of great consistency. Cooks do the same things over and over every day. The menu largely remains the same. The processes that create those menu items don't change. The schedule and setup for that workâwhen and where things happenâremain constant. Cooks don't have to field e-mails while they sauté, and their prep work isn't interrupted by 2-hour-long staff meetings. Offices can be places of inconsistency. Our jobsânot our titles, but what we actually

do

âchange from day to day and sometimes hour by hour. In the morning, we take meetings and roll phone calls; in the afternoon, we write e-mails or learn a new piece of software. Our schedules and setups fluctuate: We might work in the office one day and at a conference or on an airplane the next. As a result, regimenting and streamlining the flow of work is much easier in the kitchen. The kitchen is predictable. The office can be full of surprises.

Kitchen work has a huge physical component. It's manual laborâchopping, frying, plating, grinding, lifting, cleaning. Office work, on the other hand, is almost all mentalâtalking, writing, reading. Kitchen work is hot, difficult, and dirty. Office work can be only metaphorically so.

Chefs and cooks work with perishable resources, so their decisions, movements, and sense of time are dictated by the ticking clock, and they embody a particular sense of urgency. Office workers' deadlines are usually of a longer range, dictated more by the calendar, so we process time in a more elastic way.

Kitchen work values craft over creativity. Cooks are craftspeople,

not creatives. Although chefs and cooks do create new recipes and techniques from time to time, most of the daily work involves careful replication of existing recipes and techniques. And although much of office work can be essentially craft work, office culture is suffused with both the freedom and the burden of creating new things.

Lastly, while cooks work long hours, it's virtually impossible for them to take their work home with them. For those of us who work for corporations or small businesses, academia or professional offices, work never seems to leave us alone.

Given these contrasts it might seem like mise-en-place wouldn't apply to office life, and that chefs and cooks have little to teach us. But these dissimilarities make exploration of mise-en-place in the office compelling. Precisely because the kitchen operates under intense time pressure with perishable resources, it has developed a more refined philosophy of organization. That system abhors waste in all its forms and has evolved distinctive ways of rooting it out. Precisely because the office doesn't have to manage the efficiencies of a kitchen, the people who work in an office aren't obliged to have

any

philosophy or system at all. Even in the best corporate environments, tolerance for wasteâwaste of time, space, talent, personal energy, and resourcesâis much higher than in kitchen culture. The way that our Jeremy works, as well-intentioned and overburdened as he is, would be unacceptable in a kitchen. He doesn't plan enough. He doesn't consider his schedule. He's flustered by distractions. He leaves projects lying around half-done. He doesn't arrange or maintain his personal space. He tunes people out. He leaves incoming communication unanswered and outgoing communication unconfirmed. He panics and rushes. He repeats his mistakes. Some people might think of the office as the province of the best and brightest, and the kitchen as the refuge of the less disciplined and less capable. And yet here's the truth: Jeremy might have disappointed and angered his boss and colleagues, but his behaviors are quite common in the best corporations. He might develop a successful career without ever rectifying these shortcomings. In the best kitchens, he'd be fired.

Imagine now if Jeremy had a bit of formal training in mise-en-place. Say he had spent some time in a kitchen, enough time to pick up a few good habits. It wouldn't matter that the nature of his office work was different; the values and habits would be just as transformative for his life. Can Jeremy become, in some way, more like Chef Pasternack or the cooks who work for him? Can he become, even though he is not an owner and entrepreneur, a kind of masterâif not of the house, at least of his own space, his own schedule, his own work? What happens when you take mise-en-place out of the kitchen? What would the world be like if everybody had mise-en-place? And can you teach mise-en-place to people who aren't chefs?

Journalist and author Michael Ruhlman wished he were a better cook.

Fascinated by the differences between home cooks and their professional counterparts, Ruhlman decided in 1996 to write a book about the process of becoming a chef. He convinced the administration of the Culinary Institute of America to let him enter as a student and follow most of the curriculum for the better part of a year along with a class of degree- and career-seeking candidates.

In the book that resulted,

The Making of a Chef,

Ruhlman's story built to a pivotal moment when a blizzard struck on the night before an important exam. Ruhlman lost control of his car on the snowy, icy drive back from school to the home he shared with his wife, Donna, and baby daughter. The next morning, snow still falling, Ruhlman phoned his chef-instructor Michael Pardus to tell him he thought the drive wasn't worth the risk. He wasn't a student, so he wasn't obliged to take the exam. The chef replied with a civil but patronizing lesson about the difference between professional chefs and the rest of the world. His words answered the question at the core of Ruhlman's quest:

Chefs “get there” no matter what.