World War One: History in an Hour (5 page)

Read World War One: History in an Hour Online

Authors: Rupert Colley

Tags: #History, #Romance, #Classics, #War, #Historical

In 1914, Ireland had been on the brink of civil war – the Government Act of Ireland (or, Third Home Rule Bill) had just been passed by Asquith’s Liberal government, but its implementation was to be delayed until the cessation of war. Both Unionists and Nationalists volunteered to fight for Britain, each side hoping that by answering Britain’s call-to-arms, they would be rewarded by Whitehall after the war.

The Unionists were keen to demonstrate their loyalty, while the Nationalists hoped to prove they were not so anti-British that they could not be trusted with Home Rule. A minority of about 10,000 Nationalists, however, resented their colleague’s kowtowing to the British and planned on an uprising to take place on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916. The uprising had limited success and many viewed it as a traitorous act while their brothers were fighting for the British. Britain squandered its sympathetic support in Ireland by its harsh suppression and punishment of the Uprising’s leaders and participants.

Following a series of defeats on the Eastern Front, Tsar Nicholas II dismissed his commander-in-chief, perhaps under the influence of the Russian monk and soothsayer, Grigori Rasputin. Nicholas appointed himself in charge of Russia’s future war effort, despite his total lack of military experience.

Tsar Nicholas II, his wife and family

On 8 March 1917 the culmination of food shortages, dissatisfaction with the war and public discontent all contributed to an uprising in the Russian city of Petrograd. The city, formerly St Petersburg, had been renamed to the less Germanic-sounding Petrograd in 1914. By 12 March, there was revolution. Two million Russian soldiers deserted in the eight weeks of March and April alone. Soldiers, previously loyal to the Tsar, joined the movement. Nicholas tried to return to the city but found his way barred. The Russians had become disillusioned with their Tsar and his domineering wife who, they felt, paid too much heed to Rasputin. Having, in a matter of days, lost all authority, the Tsar abdicated. The three-century-old Romanov dynasty was no more. The Tsar, his wife, family and household were all executed by the Bolsheviks in Yekaterinburg on 17 July 1918.

In place of the monarchy, a provisional government, under Alexander Kerensky, had no intention of suing for peace, and instead promised that the new government would do ‘everything in its power to carry the war to a victorious conclusion’. However, Kerensky’s authority was undermined by workers’ councils, or ‘Soviets’, that had sprung up in the cities. One man, in exile in Zurich, was determined to end the war and bring about an international workers’ revolution. The Germans, keen to allow him to cause as much discord in Russia as possible, gave him passage back to his native land through Germany in a sealed train. His name was Vladimir Lenin.

Arriving in Petrograd on 16 April, he was soon joined by fellow revolutionary, Leon Trotsky. Lenin immediately went on the offensive – denouncing Kerensky, the war and the exploitation of Russia’s peasants, workers and soldiers.

In July, Kerensky launched the Russian army against the Germans, the Kerensky Offensive, but it failed. The Germans counter-attacked and advanced as far as Riga. This was the final straw for the Russian soldier.

In Petrograd, Kerensky went on the attack – arresting Bolsheviks, including Trotsky, and trying to restore order. Lenin disappeared to Finland and went into hiding. Kerensky’s commander-in-chief, Lavr Kornilov, was heading back to the city, fresh from his defeat to the Germans, with the intention of taking control. Kerensky released the Bolsheviks and begged Lenin to return. Kornilov’s soldiers were met by the revolutionaries at the gates of Petrograd and persuaded to down their weapons. They did – many went home; others joined the Bolsheviks. Kornilov was arrested.

On 7 November (or 25 October by the old Russian calendar), the Bolsheviks seized control of the Winter Palace, arrested members of the provisional government and declared Lenin their chairman.

Lenin addressing the masses, 20 May 1920 (Trotsky, right, stares at the camera)

Lenin and Trotsky now set about their mission to change Russia, freeing the workers and peasants from the chains of capitalism. Lenin proclaimed his Decree on Peace, inviting all belligerent nations to lay down their arms. Only Germany took him up on his offer. The armistice that officially ended the war between Russia and Germany, and her allies was signed on 16 December leading to negotiations at Brest-Litovsk in eastern Poland.

Germany’s demands of Russia were severe – the secession of Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Ukraine to the German empire – almost 30 per cent of its population. Even the Bolsheviks baulked at this and walked out of the talks. The German army prepared to make its point with a renewal of war. Lenin ordered Trotsky to sign. So on 3 March 1918, Trotsky returned to the table and signed the hated agreement, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

Germany had at last a war on one front but Ludendorff had to station a million men on the Eastern Front to discourage the Russians from revoking the treaty. Nonetheless, he was still able to transfer the bulk to the Western Front, giving the Germans a numerical superiority over the Allies. It would not last long.

Russia now had a communist government. It may have lost vast swathes of territory and a sizeable bulk of its population but it had freed itself from the war. Instead, it descended into a civil war between the Bolsheviks and the counter-revolutionaries that was to last five long years.

Germany compounded the error of sinking US ships with its U-boats by trying to draw Mexico into an alliance. In January 1917, the German Foreign Secretary, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a telegram to the German ambassador in Mexico with instructions to open negotiations with the Mexicans. He was to offer help to restore territories lost by Mexico to the US in the nineteenth century, namely New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona. The Zimmermann Telegram however was intercepted by the British. Decoded and published in their newspapers, it enraged US public opinion against Germany. On 6 April 1917, the US declared war on Germany, and their president, Woodrow Wilson, in his declaration, talked of making the ‘world safe for democracy’. The Allies, although delighted by this latest development, knew it would be many months before the US, with its small and poorly equipped army, would be fully prepared and battle-ready.

On 8 January 1918, in a speech to Congress, Wilson delivered his Fourteen Points, a programme for peace based on the principles of democracy and justice and not on punishment and reparations. Wilson hoped it would encourage the Central Powers to seek peace. Georges Clemenceau, the new French prime minister, was scathing – ‘Fourteen? The good Lord had only ten’.

While Pétain was waiting for tanks and Americans, and determined not to expose his men to any more fruitless offensives, the onus fell on Britain. Unfortunately for the British soldier, Haig was convinced that a breakthrough was still possible and argued for another great offensive. Pétain advised against it. As did Haig’s own staff. Lloyd George too, was utterly opposed. But Haig had got the backing of the Conservatives within Lloyd George’s coalition and so got his way.

It started well in June 1917 at Messines Ridge, near Ypres. The British had spent two years tunnelling underground down to a depth of 100 ft (32 m). The Germans were digging in the opposite direction, slightly higher up. Sometimes, they came so close they could hear each other. Using only handheld tools, it was an amazing feat of engineering. They dug twenty-two mines in a position beneath the German-held ridge, and stuffed them with explosives. At 3.10, the morning of 7 June, the mines were detonated all at once. Three failed to explode but the combined blast of the other nineteen was so loud as to be heard by Lloyd George asleep in Downing Street and as far away as Dublin. 10,000 Germans were killed in a trice.

Stretcher-bearers during the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), August 1917

IWM Collections, Q 5935

On 31 July, Haig launched his main attack, the Third Battle of Ypres, otherwise known as the Battle of Passchendaele. Soon the rains came, and within no time the battle scene had degenerated into a sea of mud – guns disappeared into it, tanks sunk in it, a quarter of the men killed at Passchendaele drowned in it. In August, Lloyd George personally came to visit the front line. The prime minister despaired but failed to stop its continuation. The battle wore on for another three months. On 20 November, the Canadians captured the town of Passchendaele itself and the battle finally halted. 250,000 Allies had been killed or wounded; 200,000 Germans.

On 20 November, tanks, that had proved so impractical in the mud of Passchendaele, attacked the Germans at Cambrai. There was no preliminary bombardment to warn the Germans and, for once, the British achieved a victory that could be measured in miles as opposed to feet. The public at home was delighted – for the first time, church bells rung out in celebration. Within a week, the Germans recaptured the lost ground. Nothing had changed. The bells never rang again.

Lenin had hoped that workers everywhere among the belligerent nations would follow Russia’s lead. January 1918 saw massive workers’ strikes in Berlin and other German cities and although the strikes shook the establishment, revolution did not follow. But it was enough to stir Germany into further military action. The Russians may have been out of the war but the Americans were due soon and neither the German public or the German economy would stand for much more. Ludendorff planned the last throw of the dice.

At 4.40 am on 21 March 1918, the Germans launched their ‘Spring Offensive’ on Allied positions on the Somme. In the first five hours the Germans fired over a million shells. The initial breakthrough of nearly fifty miles was spectacular. Ludendorff ordered his men westwards towards the important rail junction of Amiens. The Germans were jubilant, the Kaiser arranged for a ‘Victory’ holiday. Further south, the Germans deployed their new big artillery guns, the ‘Big Berthas’, and bombed Paris from a distance of 75 miles.

On 26 March, French general, Ferdinand Foch, was elevated to become the ‘Allied Supreme Commander of the Western Front’, leapfrogging Pétain and Haig. Foch accepted the position with a declaration of his intentions, ‘I would fight without a break . . . I would fight all the time. I would never surrender’.

Around Amiens, the Allies held the Germans in check, just ten miles short of the city. Instead, the Germans thrust on towards Hazebrouck, near the Belgium border. On 12 April, fearing for the safety of the Channel ports, Haig issued his famous order, ‘With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each one of us must fight to the end’. The Germans beat a consignment of Portuguese and re-took Passchendaele.

The war had suddenly become a war of movement again and both sides found it difficult to overcome the logistical difficulties of maintaining supplies. Now, the Americans had finally landed – initially with 180,000 troops, led by their commander, General John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing.

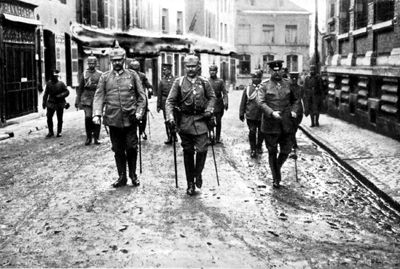

Hindenburg, Wilhelm II and Ludendorff, March 1918

Ludendorff decided the momentum had to be maintained. On 27 May, he struck at the southern end of the Western Front, over the River Aisne. By 30 May, the Germans had reached the River Marne and were now just forty miles from Paris. But again the Germans were checked, most notably in the Battle of Belleau Wood, where they were beaten back by a unit of US marines. At one point, their French, advising the US commander to retreat, received the reply, ‘Retreat? Hell, we just got here.’

In the midst of war, troops on all sides were being decimated by a global pandemic of what became known as Spanish flu. Perhaps the biggest pandemic in history, it affected a fifth of the world’s population and killed 50 to 100 million people. Soldiers were particularly susceptible, given their levels of fatigue and stress, their lack of cleanliness and unhealthy living conditions.