Write Great Fiction--Plot & Structure (16 page)

Read Write Great Fiction--Plot & Structure Online

Authors: James Scott Bell

Tags: #writing, #plot, #structure

Do that with your novel. Maintain the tension in the story until the last possible moment. As you near the end, it should look as if the opposition is the one who will win. He has everything going for him. The Lead is up against the ropes.

Only when the Lead reaches deep within and makes her move will the knockout blow be thrown.

Near the ending, you want the readers to ask, “Will the Lead fight or run away? Will the forces marshaled against the Lead simply be too much for her to face?”

To stay and fight, your Lead will have to call upon moral or physical courage, just as in the examples below:

- In

Jaws

, Brody must finally head out to sea and, with help, kill the shark. He does. - In

The Rainmaker

, Rudy must go all the way through a trial even though he has no experience. He wins. - In Dean Koontz's

Intensity

, Chyna must find a way to kill her tormentor. She finds it. - In

The Silence of the Lambs

, Clarice stays with the case in order to stop Buffalo Bill. She stops him.

Readers like to have the hero decisively defeat the opposing force. But that doesn't always have to be the case.

A good example is Jonathan Harr's

A Civil Action

, which we discussed in

chapter four

. The nonfiction book tells the story of lawyer Jan Schlichtmann's obsession to get justice for the residents of a small town whose water supply was poisoned by two huge companies. Of course, the other side, with unlimited funds, does everything to crush him, both personally and professionally. They do. But we are left with a sense of awe at how long the hero stood up under the gun.

AH!

AND THE

UH-OH!

There is one more thing you need to do to leave the reader with the ultimate reading experience. I call these the “Ah” and the “Uh-Oh.”

You get the “Ah” once the main action of the story is wrapped up. With the knockout blow administered, you need to give the reader a final scene in which something from the hero's

personal

life is resolved.

In

Midnight

, Sam Booker has brought down the villain's evil plan. But the book ends with Sam returning to try to make amends with his rebellious son. Sam embraces him, and even though their issues aren't resolved, at least the process has begun. “That was the wonderful thing,” goes the book's last line. “It

had

begun.”

This emotional resolution in the Lead's personal life makes us go “Ah.”It's like the perfect last note in a great piece of music. Look at the very last scenes in a number of thrillers, and you'll see how often this is done.

Dickens strikes this chord of personal resolution at the of

David Copperfield

:

And now, as I close my task, subduing my desire to linger yet, these faces fade away. But one face, shining on me like a heavenly light by which I see all other objects, is above them and beyond them all. And that remains.

I turn my head, and see it, in its beautiful serenity, beside me. My lamp burns low, and I have written far into the night; but the dear presence, without which I were nothing, bears me company.

Oh Agnes, oh my soul, so may thy face be by me when I close my life indeed; so may I, when realities are melting from me like the shadows which I now dismiss, still find thee near me, pointing upward!

A book can also leave the reader with a sense of foreboding, perhaps even uttering, “Uh-oh,” as he turns the last page. Charles Wilson's

Embryo

has such an ending. The book details the search for a mad doctor and the process he uses to bring forth children outside the womb. They become evil children who actually

smile

when contemplating how bad they can be.

The main story is resolved when the hero and love interest end up with what they think is a normal child. All is well. But in the final scene their little girl, Pauline, is alone outside. She finds some matches and, curious, lights one. She pitches it and it lands on her dog's back.

He suddenly jumped and whirled and tried to look back across his shoulder at what had stung him. Pauline realized what she had done and looked sad for a moment.

And then she smiled.

Uh-oh! Wilson has left us to contemplate the horror starting all over again.

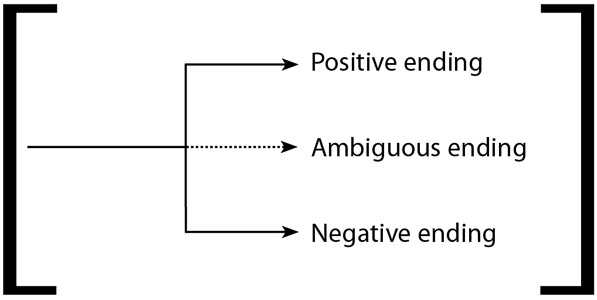

There are three basic types of endings shown in the following graph are: (1) the Lead gets his objective, a positive ending; (2) we don't know if the Lead will get his desire, an ambiguous ending; and (3) the Lead loses his objective, a negative ending.

Three Basic Types of Endings

A positive ending is found in

Jaws

. Brody kills the shark.

An ambiguous ending is found in

The Catcher in the Rye

. We don't know if Holden Caulfield will be able to make it in the world after he leaves the sanitarium.

The test of a good ambiguous ending is that it causes strong feeling, feels right, and can generate discussion. Indeed, that's what happened with Holden. Take the haunting last line: “Don't ever tell anybody anything. If you do, you start missing everybody.”

Will Holden therefore detach and never speak of anything deeply again? Will he then become a “phony” like those he deplores? Or is this some sort of Zen

koan

that shows a step toward a new grasping of life, a healing through trial?

A negative ending occurs in

Gone With the Wind

. Scarlett loses her true love, Rhett. (Margaret Mitchell cleverly added a

note

of ambiguity, with Scarlett thinking surely she will be able to get him back.)

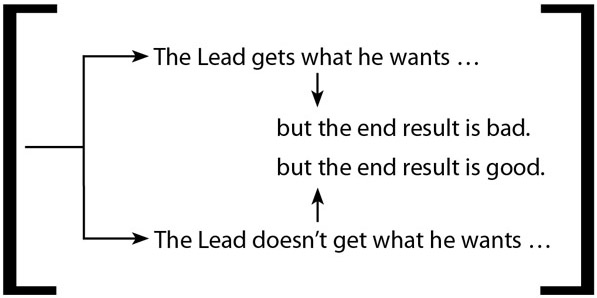

To the three basic endings, we can add a couple of complexities, which are outlined in following graph. For it may be that in gaining his desire, the Lead really has a negative

result

. Similarly, the Lead may lose his desire, yet gain something better.

Making Basic Endings Complex

An example of the first type, a gaining of desire but at a terrible cost, is found in Jack London's

Martin Eden

. Human achievement and Nietzche's will to power do not bring Eden what he's looking for. Rather, life as he chose to live it is “an unbearable thing.” He jumps off a ship into the ocean:

He filled his lungs with air, filled them full. This supply would take him far down. He turned over and went down head first, swimming with all his strength and all his will. Deeper and deeper he went. His eyes were open, and he watched the ghostly, phosphorescent trails of the darting bonita. As he swam, he hoped that they would not strike at him, for it might snap the tension of his will. But they did not strike, and he found time to be grateful for this last kindness of life.

Down, down, he swam till his arms and leg grew tired and hardly moved. He knew that he was deep. The pressure on his ear-drums was a pain, and there was a buzzing in his head. His endurance was faltering, but he compelled his arms and legs to drive him deeper until his will snapped and the air drove from his lungs in a great explosive rush. The bubbles rubbed and bounded like tiny balloons against his cheeks and eyes as they took their upward flight. Then came pain and strangulation. This hurt was not death, was the thought that oscillated through his reeling consciousness. Death did not hurt. It was life, the pangs of life, this awful, suffocating feeling; it was the last blow life could deal him.

His wilful hands and feet began to beat and churn about, spasmodically and feebly. But he had fooled them and the will to live that made them beat and churn. He was too deep down. They could never bring him to the surface. He seemed floating languidly in a sea of dreamy vision. Colors and radiances surrounded him and bathed him and pervaded him. What was that? It seemed a lighthouse; but it was inside his brain â a flashing, bright white light. It flashed swifter and swifter. There was a long rumble of sound, and it seemed to him that he was falling down a vast and interminable stairway. And somewhere at the bottom he fell into darkness. That much he knew. He had fallen into darkness. And at the instance he knew, he ceased to know.

What about the other kind, the loss that is really a gain? I must use an example from

Casablanca

, which has perhaps the most famous ending in film.

As the Lead, what is Rick Blaine's desire? Simple. He wants Ilsa, who is married to war hero Lazlo. By the end of the film, Rick can have Ilsa; she's consented to go away with him, but Rick gives her up and insists she go off with her husband.

He actually sacrifices his greatest desire for a greater good. The war effort. And for a marriage. Had he taken Ilsa away from Lazlo, it would have been at a moral cost.

So Rick is freed from the ghost of Ilsa (“We'll always have Paris”), comes back into the fight, and joins the human family again. And he gets a new friend in the bargain, the little French prefect, Louis.

What makes the ending of

Casablanca

so popular?

The element of sacrifice. Rick gives up his object of desire for a greater good.

Why is that theme so powerful? Because it is wired into our cultural consciousness. In giving up our own well-being for a greater good, we tap into the deepest yearnings of man.

As Viktor E. Frankl, author of

Man's Search for Meaning

, argued, man is on a lifelong search for meaning. Meaning does not come from isolation. Meaning is a community thing.

When someone sacrifices himself for the good of someone else, that is powerful on a gut level.

In our Western culture, the idea of sacrifice is embedded in our foundational texts and myths. Abraham was willing to sacrifice Isaac. For that he received a reward, becoming blessed by God.

Yet even Ayn Rand, the atheistic voice of “rational selfishness,” included this philosophy in her novels.

The Fountainhead

is about a man who is willing to sacrifice his own career and work, rather than let either be changed by the collective. In

Atlas Shrugged

, her heroine, Dagny Taggart, gives up the power and prestige of her railroad to uphold the dignity of human worth.

Whether you buy Ayn Rand's philosophy or not, as a fiction writer, she tapped into the right fictional dynamic.

In the

final choice

type of ending, the hero is on the horns of a terrible dilemma. He can choose a course that gets him to his objective, but at a moral cost. Or he can “do the right thing” but lose the most important goal, the thing he's hoped for throughout the novel.

As illustrated above, in

Casablanca

, Rick sacrifices his love for Ilsa for the greater good.

In the

final battle

type of ending, the hero has to sacrifice his own safety and well-being. He has very good reasons not to stay and fight. He's probably going to lose.

The great Frank Capra film,

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

, is a perfect example. Jefferson Smith (played by James Stewart) is appointed to the United States Senate on a fluke, to be a simpleton puppet of a state machine. He just doesn't know it.

When he finds out that his dream of setting aside land for a boys' camp conflicts with the plans of the machine, he discovers what a stooge he's been.

When Smith makes an attempt to buck the machine, it kicks into high gear to destroy him by getting him booted from the Senate on a trumped-up fraud charge.

There is no way he's going to be able to beat this.

But with the help of a savvy politico (played by Jean Arthur), Smith is convinced to give it one more try. He has to sacrifice his fear to do this. He has to put himself into harm's way.

Two Types of Sacrifice

Here is a simple comparison of the sacrifices in each of the two principle endings. Notice what kind of courage is required for each:

Final Choice

Lead sacrifices his

goal

:

Moral courage

Final Battle

Lead sacrifices his

safety

:

Physical courage