Writing and Selling the YA Novel (21 page)

Read Writing and Selling the YA Novel Online

Authors: K L Going

PRINT-ON-DEMAND AND E-BOOKS

It's worth mentioning both print-on-demand publishing and e-books, although these fields are rapidly changing, and at the present time I wouldn't recommend either as a path to self-publication. Print-on-demand is a type of technology where single copies of a book are printed as orders are received rather than producing an entire print run. E-books are the electronic versions of books, downloaded to and read from portable electronic reading devices. Both of these publishing venues are discussed often, sometimes being touted as the future of publishing, but both still have serious drawbacks.

Print-on-demand books tend to have higher cover prices, making them more difficult to sell, but more disturbingly, authors don't always control the rights to their books. Instead, they receive a royalty on each book sold while the publisher holds exclusive or nonexclusive rights to their titles. This is something to be aware of. If you are self-publishing, then

you

should control the rights to your book. No exceptions.

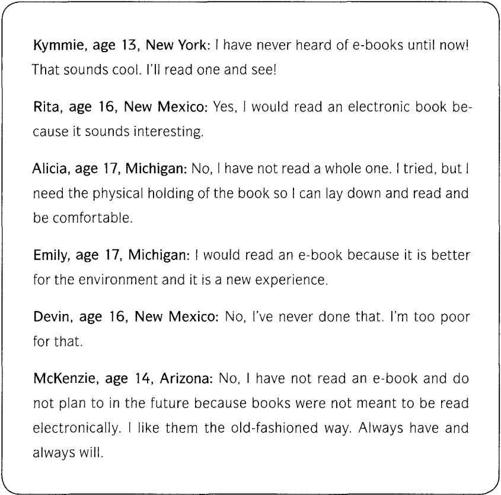

E-books present a different type of rights issue. This time, it might not be the publisher infringing on your rights, it might be your customers. As of now, e-books can easily be copied and/or illegally downloaded, cutting down on your profits. They also require expensive reading devices that prohibit many potential readers from accessing them. Most teens probably don't own an e-book reader and are unlikely to spend the money on one just to download your book.

Again, both of these fields are changing quickly, so who knows what the future will hold. One thing that can be said for teenagers is they're often way ahead of adults when it comes to accessing technology and embracing change. Even now I'm sure you will find success stories in both markets. For those of you willing to put in the extra time and research needed to explore fields in flux, you might find yourself on the forefront of innovation.

TRADITIONAL PUBLISHING

For the vast majority of us, despite the many other options available, traditional publishing will still be the path we choose. Why? This is math class, so let's consider this word problem: If a small press prints one thousand copies of your book and distributes them to X stores, and a large press prints five thousand copies of the first run of your book and distributes them to Y stores, then goes back to press and prints five thousand more, who will make more money if the book is priced the same in both cases, the author publishing with the small press or the large press? Assuming Y is greater than X, the answer seems obvious. The person publishing with the larger publishing house will make more money. In actuality, the amount of money an author makes can depend on what type of advance the author received from either house, what kind of royalties she's making, and whether there are any returns of the books sold, but for now, let's set those issues aside and focus on the advantages to traditional publishing.

The reason so many people choose larger publishing houses is because they can allow your books to reach the largest possible audience.

This, in turn, can lead to the greatest amount of profit from your work. Traditional publishing houses have large distribution networks, professional book designers who know what attracts teen readers, and marketing teams who will help your book reach teens everywhere it possibly can.

So how does one enter this world? I'll tell you right now, it isn't easy, but it isn't impossible, either. And if you're able to sell your book, the rewards can be great. Let's turn our attention to the submission process and see how you can get your manuscript into the hands of as many teens as possible.

SUBMITTING YOUR WORK

_

AGENTS VS. EDITORS

The question of whether to use an agent or submit directly to editors is one you will hear constantly discussed among writers. Since I used to work at a literary agency, one might say I'm biased when it comes to this subject. But you could also say I have the inside scoop! How many jobs have you worked at where you came away feeling as if

you would never again use their particular product? It's common to hear people say things like, "After working at that fast-food place, I will never again eat fast food." or "Since working for that computer company, I always buy from their competition." My experience has been the opposite.

Both as a former employee and as a writer who still uses their services, I absolutely recommend getting an agent if you can. What does an agent do? A literary agent acts as the middleman between authors and editors. He sends your work to publishing houses, and if it sells he negotiates your contract and takes a commission—usually 15 percent—of your earnings.

The reason some people prefer to bypass agents and submit to editors directly is twofold. First, it takes just as much time and effort to find an agent as it does to find an editor, and as with any field, you're not guaranteed to find a good one. Many people prefer to handle things on their own rather than risk ending up with an agent they're not well matched with. They can speed up the submission process by sending their material directly to the editors who can acquire it for the publishing house without having to wait for an agent to send out their work. They'd also rather not pay commission on the sale of their work. Agents receive commission on your royalties as well, so that can add up to a lot of money if your books are good sellers. Some writers feel that with a little ingenuity or a friend who's a lawyer, a writer can negotiate her own contract and save herself money in the long run.

Here are the flip sides to those arguments.

Yes, it does take a lot of work to find an agent, but once you've found one you're compatible with she can be well worth the effort. An agent spends a good portion of her time networking with editors.

They meet at conferences, have lunch together, and correspond regularly regarding established clients. An agent knows which editors are looking for different types of material, whose plate is empty and who is swamped with submissions, who has a fondness for cats and probably can't resist your story about the teen who rescues kittens from city streets, and who can't stand fantasy so if you send her your boy wizard novel it's a guaranteed rejection. Since agents have personal and business relationships with editors, your manuscript is more likely to get read and more likely to be read in a timely manner. Many publishing houses state outright that they won't accept unagented submissions.

In case this policy sounds unnecessarily harsh, I can testify to the incredible volume of material that is submitted every week to agents and editors. It's daunting to see how many people are fighting for so few publishing slots. By only accepting agented work, publishing houses are cutting down on the number of submissions and hopefully insuring a certain level of quality. This is another advantage to having an agent. Agented manuscripts arrive with a stamp of approval. Remember the final step in the scientific method we learned about in science class—replication of results? Well, when an editor sees a manuscript that's submitted by an agent, he already knows that at least one person (and probably several) liked this book enough to choose it above the rest of the pack.

I don't want to overstate my case, though. A common misconception among aspiring authors is that finding an agent means a guaranteed sale to a publishing house. When I first started working at Curtis Brown, Ltd. I had this same idea, but I quickly learned otherwise. The material that agents submit is rejected frequently. Just because an agent thinks it will sell doesn't mean it will. The market changes all the time and what strikes one person as fantastic can fail to find a fan in someone else.

But let's say your novel does sell. Agents can negotiate better contracts than the vast majority of us could on our own. They can usually get you a higher advance right up front. There are two reasons for this. First, since they're trained to negotiate contracts and they do it regularly, they know what to ask for. They know what other authors have received and what different publishing houses offer. This leads to the second part of the equation: They're not afraid to ask for what they know they can get.

Here's another word problem for you: If an editor makes an offer for 10,000 dollars on a first novel and the writer is ready to agree to this offer, but the agent says, "No, let's ask for 12,500 dollars," how much commission did the agent earn if she were charging the industry standard of 15 percent? Less the agent's commission, how much more money did the author make than he would have made if he'd accepted the original offer?

Answer:

The agent earned 1,875 dollars. The difference between the original offer and what the agent earned is 2,500 dollars. Thus the author made 625 dollars more than he would have, even after he paid the agent's commission.

Now let's tackle a second word problem: If an agent negotiates a hardcover royalty that starts at 10 percent instead of the 8 percent that was originally offered, and your book earns 100,000 dollars over the next few years, how much more money did you make off that higher royalty after the agent's commission is subtracted?

Answer:

Ten percent of 100,000 dollars is 10,000 dollars. Eight percent is 8,000 dollars. So you made 2,000 dollars more than you would have made with the lower royalty. At 15 percent, the agent's commission from 10,000 dollars would be 1,500 dollars. So you made 500 dollars

more than you would have,

even after you paid the agent's commission.

Can you begin to see how these numbers might stack up? Good agents should be able to negotiate back their fees and then some. They end up costing you nothing. And even if you do eventually pay them out of your profitable sales, the service they offer is an important one that's worth the money. Agents make sure your contract doesn't rope you into something you might later regret, and they will act as your advocate if you hit a bump in the publishing process, such as a disagreement with an editor, cover art you hate, or a change of publishing houses mid-career. Publishing doesn't always go smoothly, and when things go wrong it's nice to have someone on your side so you don't have to muddy the editorial waters by arguing on your own behalf.

TARGETING YOUR SUBMISSIONS

Regardless of whether you decide to submit to editors directly or find an agent first, you still need to know how to submit your work. Manuscript submission is a long and sometimes arduous process, so you will do well to learn all you can before you begin. You only get one shot to submit your book to an agent or editor, so you'll want to use that opportunity wisely.

Let's start with deciding who to submit to. Presumably you've narrowed your choices to agents or editors. If you re looking for agents I highly recommend submitting to agents listed in the Association of Authors' Representatives (AAR) directory found at

http://www.aar-online/

. org. The AAR holds its members to professional and ethical standards so you're far less apt to find a rotten apple.

You can search for both editors and agents through resources such as SCBWI's

Market Survey of Publishers of Books for Young People,

their

Small Press Markets Guide,

and their

Agents Directory

(all of these publications are for members only);

Children's Writer's & Illustrator's Market,

which includes information specifically for the children's and YA market; or

Jeff Herman's Guide to Book Publishers, Editors & Literary Agents,

which offers information on all types of publishers and agents. You'll find these publications are the staples every writer needs to navigate the submission waters. Not only do they include editors' and agents' contact information, but they usually give a brief description of what type of material the editor or agent prefers along with guidelines for submission. Read through these guidelines so you know which editors accept unagented material, which publishing houses won't accept e-mail submissions (few do), and which houses won't accept multiple submissions. You'll want to pay particular attention to which editors and agents handle teen fiction. This will save you a lot of time, energy, and postage.