Writing and Selling the YA Novel (7 page)

Read Writing and Selling the YA Novel Online

Authors: K L Going

As I looked at the elements involved, I realized that for me, this story idea would work best as a short story. It's clever, but clever doesn't sustain hundreds of pages. Characters do. An alternative would be to develop an interesting character who could fit into the predetermined plot, but that kind of plot-driven novel often seems forced. So, while compelling, this idea was a wrong fit for my next novel.

Figuring out which ideas are compelling and which ideas are merely clever can be one of the most difficult parts of your journey to becoming a published writer. As you gain experience, you will learn which forms of writing work best for you, and then you'll be able to decide which format most naturally suits both the idea

and

your writing style. This will save you countless hours of work and allow you to focus on the stories you can tell with passion and drive.

As a teen, English was always my favorite class. I loved to read and already kept a journal, so the idea that I could get school credit for doing these things was almost too good to be true. I devoured every book the teachers assigned and fell in love with most of them—even the classics. If you'd asked me back then what made me love the books I read, I'm not sure I would've been able to answer. They didn't seem to have much in common. I read from every genre and loved most styles of writing. Like many teens, I was just as apt to pick up an adult novel as a teen novel, and my bookshelf was full of books like

Wuthering Heights

shelved side by side with the newest R.A. Salvatore fantasy novel.

Now as an adult I look at the books I've loved over the years and can see that they all share one thing in common: great characters. Whether it's Heathcliff or Drizzt Do'Urden, the characters hook me into a book and make me want to keep reading. It was the love of character that made English my favorite class year after year, and creating

5i

i

unique characters is now my favorite part of being an author. Ideas are wonderful, but they won't go very far without interesting, lovable, or infuriating characters to embody them.

In Nancy Lamb's

The Writers Guide to Crafting Stories for Children,

she writes: "What happens to characters—how they suffer and celebrate, how they meet challenges, overcome obstacles and find redemption—is the heart and soul and spirit of story." This is true no matter who your audience is. Whether you're writing for teens, kids, or adults, creating memorable characters is what elevates an idea from a novelty to a story with substance that will draw us in and make us care about the outcome. If your audience invests in your characters, whether that investment comes in the form of love, hate, or morbid fascination, they'll keep turning the pages and following the story until the bitter end.

So what makes a good character? Why do some characters live while others fall flat? How can you create teen characters who are both believable and sympathetic? In this chapter we'll take a look at creating the characters who will bring your stories to life.

WHAT MAKES A CHARACTER?

_

Understanding character begins with understanding people. What makes them tick? How do we relate to others? How do people grow and change over the course of a lifetime? How are teenagers different from adults and children?

Every human being has certain attributes, but those attributes are always in flux. We have physical attributes such as eye color, hair color, age, weight, and height, as well as myriad other features that make us unique—large ears, a small nose, or exceptionally big feet.

Many of these physical traits will change as we grow and mature, and teen characters, especially, are in transition. Their bodies are growing, and this growth will have a vast array of consequences that will affect other attributes.

For example, physical changes such as puberty often lead to changes in personality, and personality traits are a big part of defining a character. Teens can be irritable, kind, stingy, open, rude, false, generous, conniving, hyper, morose, or curious, just to name a few. They are often many of these things simultaneously, and over the course of a lifetime each person will embody almost every personality trait there is.

Our personalities reveal themselves through our speech, actions, and body language. Every person has a unique way of talking, walking, sitting, eating, sleeping, and doing just about any activity you can think of. We all have habits and idiosyncrasies, but again, these habits don't stay the same forever. Consider how you acted when you were a teen. Do you ever look back and laugh at some of the ways you tried to seem grown up? Maybe you wore too much makeup or emulated your favorite pop star. Or maybe you look back and feel sad that you've lost some of the idealism you possessed when you were younger. Teens are often purposefully trying to shape their habits, looking to mold themselves into the people they'd like to become, and those imagined future selves might be rich and famous, or they might be saving the world. Or both!

Watching what a character does or does not do can reveal what she wants and help create a fuller sense of who she is both physically and emotionally. This is especially true when we reveal the reasons behind her actions. Although different people may appear to make similar decisions, our choices are based on our varied life experiences. When

we reveal a character's history and inner life, in addition to showing his actions, we shed light on his motivations, attitudes, desires, and struggles, and this adds depth to our portrayal.

MAKING CHOICES

_

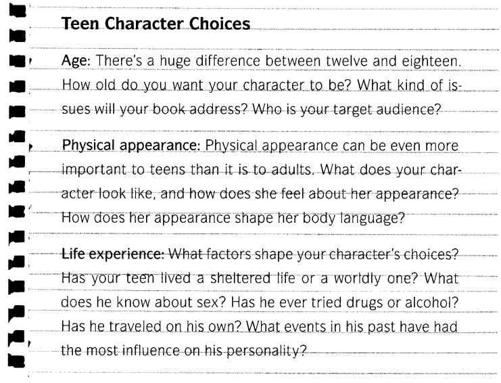

Do you have the feeling that all the attributes listed above still only scratch the surface of what defines a character? If so, you're right. Each character we create is a totally distinct person, and it's our job to reveal them to the world. But there's a wealth of information that can be conveyed about any human being, and teens are especially complex because they are still figuring out who they are and what roles they want to take in life. So how do we give the reader an accurate portrait?

We do it by making choices.

Part of what it means to be an author is deciding which information to convey to your reader and how to convey it. Writing isn't just about putting words on a page; it's about artistry. Like any artist, you'll need to make decisions about what to include or exclude in order to produce the most impact or the greatest beauty.

When it comes to character development, choices are essential. Obviously you can't describe every character trait—if you did, you'd fill entire volumes with description and there'd be no room for anything to actually

happen

in the story, nor would there be any artistry. Instead, choose which features best define your character; this description can be a mix of physical traits, personality, backstory, and character choices.

Perhaps the easiest way to think about this decision-making process is to imagine I've asked you to describe your best friend. If you

tried to tell me everything about her, it would take forever because people are always changing, and just about the time you told me what your friend was like she'd have changed clothes, hairstyle, and attitude, and moved on to some new activity. So, instead of trying to tell me everything, you'd tell me the important things—the things I most needed to know to get an accurate picture of her.

You might tell me the basics of what she looks like, such as hair color and whether she was tall or short, skinny or full-figured. You might also include some characteristics that make her unique. Maybe you'd tell me her skin color or religious beliefs, or perhaps you'd mention her thin lips or large nose. But mostly, I imagine you'd tell me what kind of person she is, and you'd probably use examples of things your friend has done or said to convince me of your points.

... and on top of everything else, she's brilliant. She was valedictorian of her graduating class and she got a scholarship to Yale.

She's so funny. Every time we go out, she's the life of the party.

You might also tell me something of your friend's personal history to further illuminate her character.

I love her, but she can be difficult to deal with. She's very temperamental, but I know it's because she had a tough life growing up with two alcoholic parents. Considering all she's been through, she's a real strong person. Once you're her friend she's fiercely loyal.

Some people think she's shallow because she parties so much, but honestly, she's the most generous

person I know. Her family was poor when she was young, so she has a strong desire to help needy children.

People are complex—we aren't easily summed up by one or two descriptions. Teen characters are no different. To reveal them, we must draw from a palette that includes every available trait, but we must also make choices about which traits most clearly define the person we're describing.

What we most need to know about a character is what makes him who he is and what will drive his actions. Many times, especially for teens, physical appearance plays a large part in this. An awkward teen will behave very differently from an effortlessly beautiful one. Not only will she make different choices, she will move differently through space. Race, sexuality, or family background can also affect our body language, our worldviews, and the decisions we make.

Each piece of the character puzzle is important, but every story will require different information to be revealed. For example, you might think race is an essential trait that an audience must know in order to "see" a character in their mind's eye, but Virginia Euwer Wolff, in her books

Make Lemonade

and

True Believer,

made a deliberate choice not to reveal the race of her characters. Wolff wanted readers to make the characters into whatever race they needed them to be. This is a risky choice that takes a lot of skill to pull off, but through her insights into the characters' hearts and minds, we're able to feel as if we know them even while we're missing a large piece of their physical description.

This is not only an example of an author making a choice, it's a choice that illustrates what's truly essential about defining character.

While physicality is important, in the end, it's what characters do and say that makes them real to a reader.

Think about the characters you create. What will your reader need to know to make them real? Do you allow for complexity? How does a character's physical appearance affect his mental state? Instead of falling back on the tried-and-true descriptions of hair color, eye color, and one or two dominant personality traits, consider what truly defines each of your characters. What makes them unique individuals, different from all others? Choose the information—whether it comes in the form of physical appearance, body language, or back-story—that will best reveal your character to your reader, and you'll find that your story will come to life.

f