Writing Home (14 page)

Authors: Alan Bennett

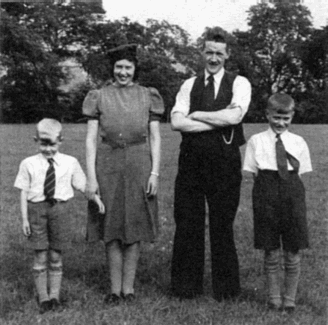

1 A. B. (left) and elder brother Gordon (right) with Mam, Filey, 1937

2 Mam, A.B., Gordon and Dad with Weatherhead, Byril Farm, Wilsill, 1940

3 Nidderdale, 1942

4 Aunty Kathleen, Grandma Peel, Mam and A. B., Morecambe, 1948

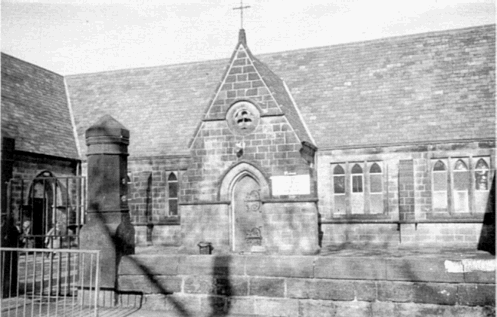

5 Upper Armley National School, Leeds

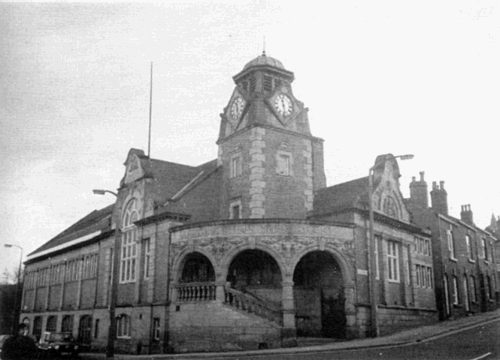

6 Armley Branch Library, Leeds

7 Redmire, 1952

8 With Michael Frayn, Bodmin, 1954

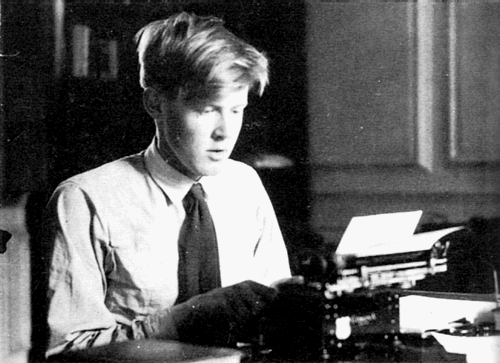

9 Oxford, 1955

10 Otley Road, Leeds, the Bennetrs’ house and shop (far right)

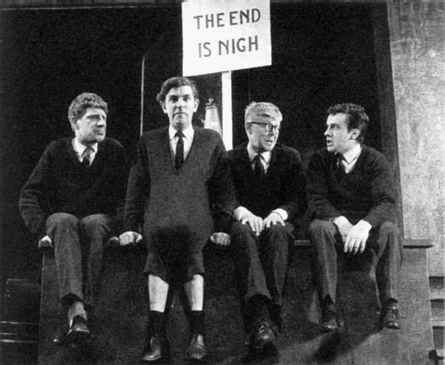

11 Walking on the beach at Brighton, April 1961

12 and 13 Dudley Moore, Jonathan Miller, Peter Cook and A. B. in

Beyond the Fringe

, May 1961

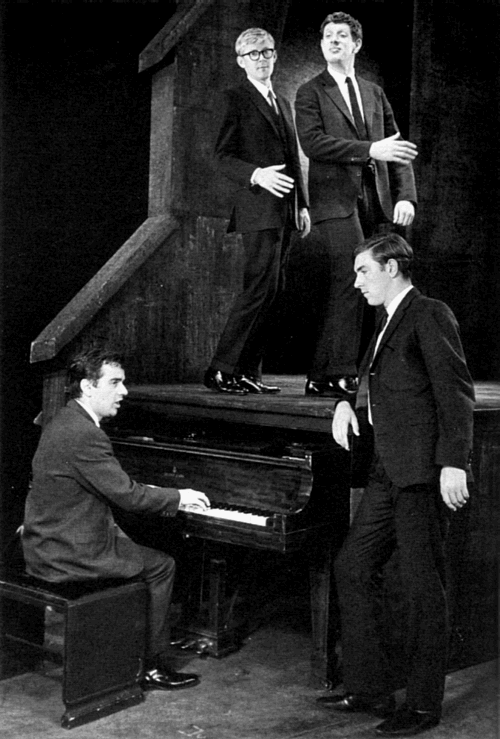

14 Dudley Moore, Jonathan Miller, Peter Cook and A. B. in

Beyond the Fringe

, May 1961

5 May 1989

. ‘Mr Bennett?’ The voice is a touch military and quite sharp, though with no accent to speak of and nothing to indicate this a man who must be over eighty. ‘You’ve sent me a letter about a Miss Shepherd, who seems to have died in your drive. I have to tell you I have no knowledge of such a person.’ A bit nonplussed, I describe Miss Shepherd and her circumstances and give her date of birth. There is a slight pause.

‘Yes. Well it’s obviously my sister.’

He tells me her history and how, returning from Africa just after the war, he found her persecuting their mother, telling her how wicked she was and what she should and shouldn’t eat, the upshot being that he finally had his sister committed to a mental hospital in Hayward’s Heath. He gives her subsequent history, or as much of it as he knows, saying that the last time he had seen her was three years ago. He’s direct and straightforward and doesn’t disguise the fact that he feels guilty about having her committed yet cannot see how he could have done otherwise, how they never got on, and how he cannot see how I have managed to put up with her all these years. I tell him about the money, slightly expecting him to change his tune and stress how close they had really been. But not a bit of it. Since they hadn’t got on he wants none of it, saying I should have it. When I disclaim it too, he tells me to give it to charity.

Anna Haycraft (Alice Thomas Ellis) had mentioned Miss S.’s death in her

Spectator

column, and I tell him about this, really to show that his sister did have a place in people’s affections and wasn’t simply a cantankerous old woman. ‘Cantankerous is not the word,’ he says, and laughs. I sense a wife there, and after I put the phone down I imagine them mulling over the call.

I mull it over too, wondering at the bold life she has had and how it contrasts with my own timid way of going on – living, as Camus said, slightly the opposite of expressing. And I see how the location of Miss Shepherd and the van in front but to the side of where I write is the location of most of the stuff I write about; that too is to the side and never what faces me.

Over a year later, finding myself near the village in Sussex where Mr F. lived, I telephoned and asked if I could call. In the meantime I’d written about Miss Shepherd in the

London

Review of Books

and broadcast a series of talks about her on Radio 4.

17 June 1990

. Mr and Mrs F. live in a little bungalow in a modern estate just off the main road. I suppose it was because of the unhesitating fashion in which he’d turned down her legacy that I was expecting something grander; in fact Mrs F. is disabled and their circumstances are obviously quite modest, which makes his refusal more creditable than I’d thought. From his phone manner I’d been expecting someone brisk and businesslike, but he’s a plumpish, jolly man, and both he and his wife are full of laughs. They give me some lovely cake, which he’s baked (Mrs F. being crippled with arthritis) and then patiently answer my questions.

The most interesting revelation is that as a girl Miss S. was a talented pianist and had studied in Paris under Cortot, who had told her she should have a concert career. Her decision to become a nun put an end to the piano, ‘and that can’t have helped her state of mind’ says Mr F.

He recalls her occasional visits, when she would never come in by the front door but lope across the field at the back of the house and climb over the fence. She never took any notice of

Mrs F., suspecting, rightly, that women were likely to be less tolerant of her than men.

He says all the fiancé stuff, which came via the nuns, is nonsense; she had no interest in men, and never had. When she was in the ambulance service she used to be ribbed by the other drivers, who asked her once why she had never married. She drew herself up and said, ‘Because I’ve never found the man who could satisfy me.’ Mystified by their laughter she went home and told her mother, who laughed too.

Mr F. has made no secret of the situation to his friends, particularly since the broadcasts, and keeps telling people he’s spent his life trying to make his mark and here she is, having lived like a tramp, more famous than he’ll ever be. But he talks about his career in Africa, how he still works as a part-time vet, and I come away thinking what an admirable pair they are, funny and kind and as good in practice as she was in theory – the brother Martha to his sister’s Mary.

Sometimes now hearing a van door I think, ‘There’s Miss Shepherd,’ instinctively looking up to see what outfit she’s wearing this morning. But the oil patch that marked the site of the van has long since gone, and the flecks of yellow paint on the pavement have all but faded. She has left a more permanent legacy, though, and not only to me. Like diphtheria and Brylcreem, I associate moths with the forties, and until Miss Shepherd took up residence in the drive I thought them firmly confined to the past. But just as it was clothes in which the plague was reputedly spread to the Derbyshire village of Eyam so it was a bundle of Miss Shepherd’s clothes, for all they were firmly done up in a black plastic bag, that brought the plague to my house, spreading from the bag to the wardrobe and from the wardrobe to the carpets, the appearance of a moth the signal for frantic clapping and savage stamping. On her death my vigorous

cleaning of the van broadcast the plague more widely, so that now many of my neighbours have come to share in this unwanted legacy.

Her grave in the St Pancras Cemetery is scarcely less commodious than the narrow space she slept in the previous twenty years. It is unmarked, but I think as someone so reluctant to admit her name or divulge any information about herself, she would not have been displeased by that.