Writing Home (42 page)

Authors: Alan Bennett

29

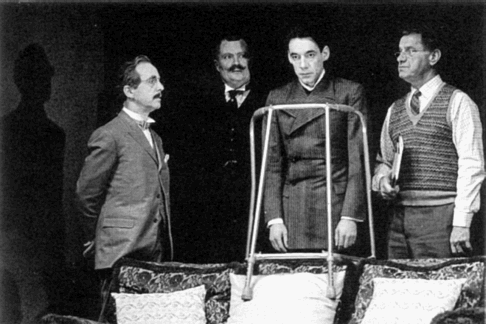

Kafka’s

Dick

, Royal Court Theatre, September 1986 (left to right: Andrew Sachs, Jim Broadbent, Roger Lloyd Pack, Geoffrey Palmer)

30

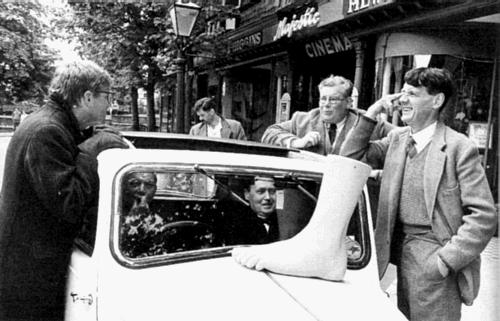

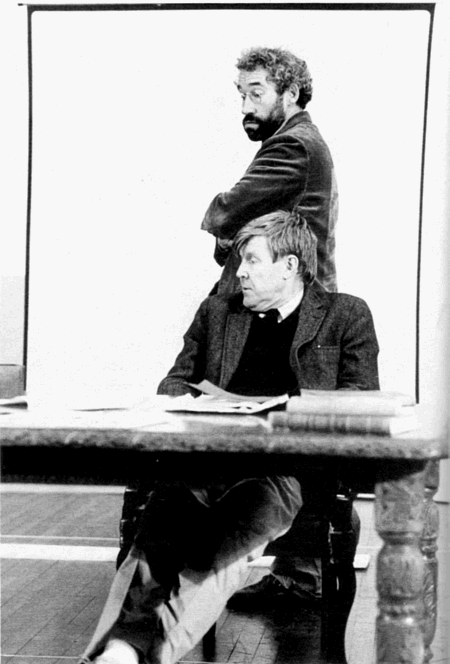

Kafka’s Dick

, Jim Broadbent and Roger Lloyd Pack

31

A Private Function

, Barnoldswick, May 1984 (left to right: A. B., Denholm Elliott, Bernard Wrigley, John Normington, Richard Griffiths, Michael Palin)

32

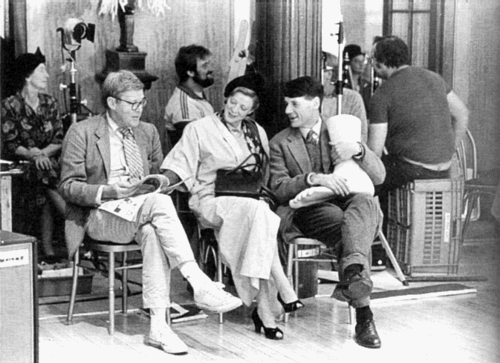

A Private Function

, Bradford Art School (left to right: A. B., Maggie Smith, Michael Palin)

33

A Private function

, Ilkley, With Betty

34 Keith McNally and Russell Harty, New York, 1979

35 With Craig Raine, Sue Townsend and the Orel writers, USSR, May 1988

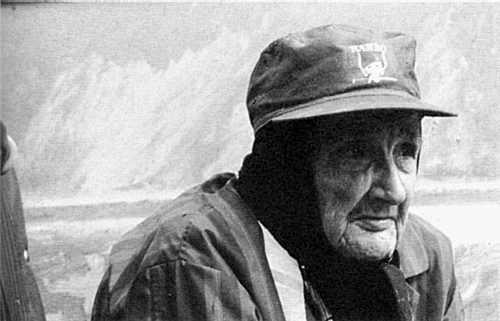

36 and 37 Miss Shepherd, 1988

38 With Simon Callow rehearsing

A Question of Attribution

, Royal National Theatre, November 1988

Dundas was much older than I have made him, but, dramatically, Pitt needs a friend or else he would never unburden himself at all. Thurlow, foul-tongued and ‘lazy as a toad at the bottom of a well’, was well known to be a twister. When he made the speech on the King’s recovery, quoted in the play – ‘And when I forget my sovereign, may God forget me’ – Wilkes, who was seated on the steps of the throne, remarked, ‘God forget you? He’ll see you damned first!’

Queen Charlotte was every bit as homely and parsimonious as she’s presented, stamping the leftover pats of butter with her signet so that they would not be eaten by the servants. Her name is preserved in Apple Charlotte, a recipe that uses up stale bread. I thought I had caught her rather well until Janet Dale, who was playing her, said that the game little wife was a part to which she was no stranger: not long ago it was the first Mrs Orwell, and more recently Mrs Walesa. ‘“Have another cup of tea, Lech, and let Solidarity take care of itself …” Solidarity,

Animal Farm

or porphyria, I’m always the plucky little woman married to a hubby with problems.’

There are some fortuitous parallels with contemporary politics; and had the play been written before the downfall of Mrs Thatcher there would have been more. Pitt’s ‘kitchen principles’ were not dissimilar to hers, and one can see that Dundas having Willis redraft the bulletin while Pitt keeps his hands clean is reminiscent of Mrs Thatcher’s conduct in the Westland affair. Thinking that the Regency Bill must pass and that he faces imminent dismissal, Pitt says that he needs five

more years.

*

The audience laughs. But what politician doesn’t? Pitt of course got them, but what he actually meant was five more years of peace, and these he didn’t get. Mrs Thatcher’s fortunes were made by a war that came just in time, Pitt’s ruined by a war which (as Fox thought) should not have come at all. The audience applauds again when Pitt, reviewing his seemingly bleak future, says that having been Prime Minister he does not now intend to sit on the back benches and carp. This isn’t an easy gibe at Mr Heath, for whom I’ve got some sympathy. Pitt had always aspired to be Prime Minister, but on his own terms; in 1783 he had even refused the King’s invitation to form a ministry because he was not yet ready; defeated, he would never have played second fiddle to anybody.

Any account of politics, whatever the period, must throw up contemporary parallels. I think if I had deliberately made more of these it would have satisfied or pandered to some critics who felt that that was what the play should have been more about. But it is about the madness of George III – the rest amusing, intriguing, but incidental. Mention of the critics, though, reminds me that one of the jokes when we were rehearsing the play was that it would take audiences ten minutes to reconcile themselves to the fact that it wasn’t set in Halifax. Such jokes tempt fate, and I’m told that the critic of the

Independent

spent most of his notice regretting that it wasn’t more Trouble at t’Mill.

Though I have known sufferers from severe depression, I have had little experience of mental illness or of the discourse of the mentally ill, since depression, though it can lead to delusions, doesn’t disorder speech. Of course, as Greville cautions Willis in the play, the King’s discourse is slightly disordered to begin with, not normal anyway, and his idiosyn-

cratic utterance has to be established in the audience’s mind before it gets more hurried and compulsive and he starts to go off the rails. Even then Willis has to tread warily, because behaviour which in an ordinary person would be considered unbalanced (talking of oneself in the third person, for instance) is perfectly proper in the monarch. Some of the contents of the King’s mad speech I cribbed from contemporary sources, such as John Haslam’s

Illustrations of Madness

, an account of James Tilly Matthews, a patient in Bethlem Hospital in 1810. Other features of the King’s mad talk – his elaborate circumlocutions (a chair ‘an article for sitting in’), for instance – are characteristic of schizophrenic speech.

What was plain quite early on was that where mad talk was concerned a little went a long way; that while it is interesting to see the King going mad, and a great relief to see him recover, when he is completely mad and not making any sense at all he is of no dramatic consequence. Since what he is saying is irrational it cannot affect the outcome of things, and so is likely to be ignored: thus an audience will attend to what is being done to the King but not to what he is saying. There was also a difficulty with the sheer quantity of the King’s discourse (on one occasion he was reported as talking continuously for nine hours at a stretch). Two minutes’ drivel, however felicitously phrased, is enough to make an audience restive, and, though what the King is saying is never quite drivel, the volume of it has to be taken down to allow other characters to speak across him – subject sense taking precedence over regal nonsense. Of course speech is not the half of it, and without Nigel Hawthorne’s transcendent performance the King could have been just a gabbling bore and his fate a matter of indifference. As it is, the performance made him such a human and sympathetic figure the audience saw the whole play through his eyes.

The final scene of the play proved the most difficult to get

right. I knew from the start that the play must end at St Paul’s, when the nation gave thanks for the King’s return to health. As originally written, the doctors emerged still quarrelling as to who deserved the credit for their patient’s recovery. Then Dr Richard Hunter, joint author of

George III and the Mad

Business

, materialized in modern dress to tell the eighteenth-century doctors that they were all wrong anyway and that the King was not mad but suffering from porphyria. The discussion that followed was long and detailed – too much so for this stage of the play – and was made longer when the politicians emerged and started quarrelling too. Finally the King himself came out, found the doctors disagreeing over the body of the patient and the politicians disagreeing over the body of the state, said to hell with it all, and, taking his cue from Hunter, described how he would eventually end up mad anyway.

Nigel Hawthorne felt, I think rightly, that he couldn’t step out of his character so easily and that if he did the audience would feel cheated. It was Roy Porter who suggested that Richard Hunter’s mother, Ida Macalpine, was as much responsible for

George III and the Mad Business

as her son and that in the interest of literary justice (and political correctness) she should be the voice of modern medicine. Accordingly I wrote the brief scene just before the finale where she explains to the sacked pages (who had been the only ones to take notice of the King’s blue piss) what this symptom meant. Whereas in a film one could deal with this explanation in the final credits, I felt at the time the play opened that the facts had to be set out and the matter settled within the play. Now I’m less sure, though the scene has a structural function as it enables the King and Queen to nip out of bed and into their togs ready for the finale.

One ending I was fond of, though it was determinedly untheatrical, and perhaps just an elaborate way of saying that too many cooks spoil the broth; still, it’s the nearest I can get to

extracting a message from the play. The King and Queen are left alone on the stage after the Thanksgiving Service and they sit down on the steps of St Paul’s and try to decide what lessons can be drawn from this unfortunate episode.

KING: The real lesson, if I may say so, is that what makes an illness perilous is celebrity. Or, as in my case, royalty. In the ordinary course of things doctors want their patients to recover; their reputations depend on it. But if the patient is rich or royal, powerful or famous, other considerations enter in. There are many parties interested apart from the interested party. So more doctors are called in, and none but the best will do. But the best aren’t always very good, and they argue, they disagree. They have to, because they are after all the best and the world is watching. And who is in the middle? The patient. It happened to me. It happened to Napoleon. It happened to Anthony Eden. It happened to the Shah. The doctors even killed off George V to make the first edition of

The

Times

. I tell you, dear people, if you’re poorly it’s safer to be poor and ordinary.

QUEEN: But not too poor, Mr King.

KING: Oh no. Not too poor. What? What?

*

When the play was put on in America the line only worked when altered to ‘

four

more years’.