Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back (39 page)

Read Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back Online

Authors: Liz Owen

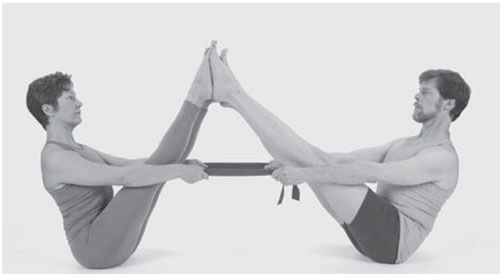

FIG. 5.21

Full Boat Pose, Partner Variation

Before we move on to our last abdominal core pose, try a playful variation of Boat Pose with a partner in order to practice it with more support for your lower back. Sit facing each other in step 1: Grounded Bent-Knee Pose. With your hands on the floor, place the soles of your feet against the soles of your partner's feet, and hold each other's wrists, or hold belts as shown in figure 5.22. Maintain this position for a few breaths while you find your balance, then with an exhalation slowly lift your legs up (all four of them!) toward the ceiling, one side at a time. Remain in the pose for ten to fifteen seconds. Slowly bend your knees, bring your feet back down to the ground, and release your hands.

FIG. 5.22

Half Boat Pose

Strengthen | Ardha Navasana

This may sound backward, but it's true: when you're comfortable in Full Boat Pose, it's beneficial and abdominally strengthening to move from it into Half Boat Pose. In Half Boat, your body forms a slight concave curve rather than the sharp V-form of Full Boat.

Start in Full Boat Pose. When you feel steady, take your hands behind your head and place your fingers lightly on the back of your skull. Your elbows should open out to the sides. Draw your navel down toward your spine and knit your abdominal wall together any amount possible. With your next exhalation, lower your legs almostâbut not all the wayâto the floor. Now lower your trunk just a bit toward the floor. Keep your lower back off the floorâyou should be balanced on your buttocks. Your eyes should gaze straight at your feet (

fig. 5.23

). If this is a challenging pose for you, place a folded blanket behind your hips before you begin and use it to support your sacral band, as shown in the photo.

FIG. 5.23

Hold Half Boat Pose as long as your body enjoys its fierceness, then lie down on the floor and relax. Place your hands on your abdomen and breathe up into them, feeling your abdominal muscles release any tension that might have crept in during your practice. One more time, congratulate yourself on cultivating strength and tone in your body that will carry you through your life as well as your yoga practice.

Relaxing Bent-Knee Twist, Child's Pose, and Deep Relaxation

Rest | Jathara Parivartanasana Variation 3, Balasana, and Shavasana, Variation 4

Be sure to rest your body after you've completed your abdominal practice. A gentle twist can feel exceptionally good after abdominal poses. Practice

Relaxing Bent-Knee Twist

, and

Child's Pose

. Then rest in Deep Relaxation for five minutes or longer, resting into the image of the inner fire of your abdominal core, illuminating, warming, and enlivening your whole self.

6

Y

OUR

M

IDDLE

B

ACK,

U

PPER

B

ACK AND

N

ECK

W

HAT DOES YOUR NECK

have to do with a healthy lower back? Asking that question is like asking what the roof of a building has to do with its foundation. If the building's foundation is uneven, the roof will be askew and cause leaks, rot, and all sorts of other problems. If the roof is not pitched correctly, those problems will (literally!) trickle down to the foundation, undermining it and potentially putting the whole structure at risk.

The architecture of your body is no different, in this way, from the architecture of a building. We have discussed throughout our journey so far that a healthy spine is a smooth, flowing S-curve. It must, therefore, be clear that your middle back, upper back, and neckâbeing parts of your spinal columnâhave a direct relationship to the comfort of your lower back, sacrum, and hips. The curve goes from top to bottom, and every inch of it impacts the whole.

Our work in this chapter starts with taking a long, hard look at your posture. Whatever you do in your personal and professional life affects how you carry yourself. Eating, sitting, driving, reading, carrying children, typing, texting, and sleeping are just a few of the activities that involve

your middle back, upper back, and neck. You can probably name a time when you were doing something “normal,” like making a bed or tying a shoelace, when all of a sudden a muscle in your upper back or neck went into a twinge, knot, or spasm. If you've had lower back pain for even just a few weeks, you know how your upper back and neck tend to respondâthey can overwork to compensate for the lower back and tighten up because of itâand how that affects your movements.

The majority of middle and upper back issues are either cases of myofascial pain from improper postural habits, injuries from overuse or repetitive motion, or spinal joint dysfunction, where a vertebra is abnormally positioned or out of alignment with the rest of the spine.

1

The pain can feel like aching discomfort in the upper back and neck, tenderness around the neck or shoulder blades, or sharp pain that radiates through the neck, upper back, or upper chest and arms. In such cases, you often lose range of motion, especially in the neck and shoulders.

2

Other conditions that produce middle and upper back and neck pain include scoliosis, spinal stenosis, degenerative disk disease and injuries resulting from whiplash.

3

In this chapter, you'll explore how you can create both fluidity and tone in your middle back, upper back, and neck as a means of support for your journey into lower back health, as well as for their own sake. Because all the parts of your spine are inextricably connected to one another, I'll be referring back to poses you've practiced in other chapters that have additional benefits in your upper back and neck. You'll also learn new poses that will guide your upper back and neck a little farther toward releasing tension and “reshaping” themselves back toward their natural healthy curvatures.

T

HROUGH

W

ESTERN

E

YES: THE

P

HYSICAL

V

IEW

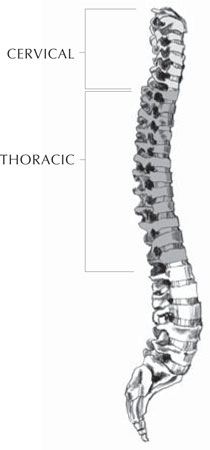

Anatomically speaking, this chapter will complete our journey up the spine, through your thoracic and cervical spines (

illustration 17

).

The middle and upper back, or thoracic spine, contains twelve vertebrae. It begins at the top of your lumbar spine and grows thinner and narrower as it climbs upward to its meeting point with your cervical spine (neck), just below the tops of your shoulders.

The character of your middle and upper back is quite different from that of your lower back. You may recall that I described your lumbar spine as a flexible stack of bones, with the back of the hip bones to restrict their

movement at lumbar vertebra L5. I also mentioned the connection between your lumbar spine and your cervical spine: They both have concave curvesâif they're healthy, that isâand more range of motion than the thoracic spine. Because of that, both your lumbar and cervical spines are more vulnerable than your thoracic spine to injuries and painful conditions including herniated disks and degenerative disk disease.

In contrast to the relative freedom of the lumbar and cervical spines, your thoracic spine is well connected to surrounding bones, specifically your ribs and breastbone. Your thoracic spine, ribs, breastbone, and the cartilage that connects the latter two form your rib cage, which surrounds and protects the thoracic cavity and the organs within it, including your heart and lungs. Because of its connections to the ribs and breastbone, your thoracic spine is designed for upright twisting and some forward bending (but not a lot); it has much less range of motion in backbends and side-bending than your lumbar spine does.

The cervical spine forms the support for your skull. The top cervical vertebra, C1, is the atlas, the base of your skull (remember, spinal vertebrae are numbered from top to bottom). Below C1 is C2, the pivot point upon which C1 rotates. C1 and C2 form the joint that connects your skull with your spine.

4

There are seven cervical vertebrae in allâyou can often see or feel C7 as a bony protuberance just below the tops of the shoulders.

Illustration 17. Your Thoracic and Cervical Spines

The Interconnectedness of Your Spine

As I said before, we'll start by thinking about poor posture, and the havoc it can wreak on your entire back body. We'll look at a few dysfunctional ways many of us hold ourselves, and the respective chains of discomfort those poor postural habits can cause.

Trouble often starts with tight hip flexor (psoas) muscles, which pull the sacral and hip bones forward, tightening up your lower back. As I've noted earlier, this leads to an exaggerated lordosis, which pulls your lower back muscles forward toward your front body. Tight psoas muscles can also pull one or both legs up, which results in a functional leg-length difference, causing further shear in the sacral joints. Because your body is always trying to find its balance, your upper back responds to a lordosis by an exaggerated rounding and hunching of the thoracic spine called a kyphosis. Excessive kyphosis can also be caused by poor postural habits or repetitive strain on the thoracic muscles, such as the shoulders shifting forward in relation to the hips in a seated positionâhm, computers, anyone?

While poor posture does not directly cause pain, it does create vulnerability to injury in the middle back, upper back, and neck. Kyphosis causes the shoulder blades to slide away from the spine, chronically overstretching and weakening the muscles around the shoulder blades.

5

It has a profound effect on the front of your chest as well, shortening and tightening the myofascia of the upper chest, which then pulls on your upper back and neck muscles again, overstretching and weakening the myofascia even further. The spaces around your heart, lungs, and diaphragm then become constricted and tight. Because your body is still trying to bring itself into balance, your head shifts forward, creating tension and tightness in your neck muscles. Keep this in mind throughout this chapter, especially as you practice both active and supported backbendsâback bending, by bringing the spine into extension, decreases a kyphotic curve.