Your Band Sucks (17 page)

Authors: Jon Fine

Even some bands that seemed primed to succeed crapped out. Urge Overkill had their look and concept extraordinarily well thought out. Their cover of Neil Diamond's “Girl, You'll Be a Woman Soon” gave them a star turn on the soundtrack of

Pulp Fiction

. For their 1993 major-label debut,

Saturation

, they had the full promotional power of Geffen's machinery behind them: significant commercial radio airplay, a tour with Nirvana and Pearl Jam, and a video for “Sister Havana” that ended up in MTV's

Buzz Bin

, back when that all but guaranteed you'd soon hang a gold or platinum record on your wall. To date

Saturation

has sold about 270,000 copies. A total that would have any indie label freaking out with joy. But for a band in the nineties that received a full-on major-label push, that figure is flat-out disappointing. “The people spoke,” Urge's Ed Roeser told me. “It didn't work out.” To employ the gentlest form of understatement, drink and drugs became a problem, and the band's dark and underbaked follow-up, 1995's

Exit the Dragon

, tanked. Urge had played a glamourpuss-rock-star shtick for laughs pretty much since they started, but now it looked like they could no longer tell which parts were a joke and which weren't, which even Ed admits now. He quit, and the band fell apartâor vice versaâand fell apart in the worst way. Many fans never forgave them for leaving for more-monied pastures. Smarter ones just questioned the wisdom of their tactics. “They probably would have been a much more successful huge rock band if they hadn't been

trying so hard

to be a successful huge rock band,” said Tortoise's Doug McCombs.

As for me, after indie pop triumphed and virtually all indie-to-major signings failed, I ended up getting into the continuum of sludgy hard rock bands that ran from Blue Cheer to Saint Vitus and Melvins to Kyuss and Sleep, the most recent examples of which were being described with the unfortunate term “stoner rock.” In these bands I found the physicality and visceralness I no longer found among my indie brethren. Unfortunately I also found a decided Doctor Rock-ness to many of the musicians. Dave Sherman, then the bassist in Spirit Caravan, once told me he was calling his new band Earthride, “because we're all just”âhere he paused, looking off into space, before concludingâ“riding the earth.” Then he described the art he wanted on the cover of Earthride's first album, a blond woman straddling the earth, at which point he started demonstrating that image. (I'd love to be able to say that albumâwhose cover features no such blondeâis pretty great. But it isn't.) By then I'd abandoned many of my indie rock prejudices, but I just couldn't hang with how these guys defaulted to standard party-time rock modes. Nor how, once you got past the best of this breed, quality declined so precipitously. Nor how, for many of them, punk rock never happened. Also, theirs was a different tribe. Outsiders, yes, but bikers, not nerds. No way I'd ever pass for one of them, even with my long hair.

***

AROUND 2003 TED LEO MET WITH ANOTHER MAJOR-LABEL

A&R guy, who had a slightly different spiel: “We want to think of you as another Bruce Springsteen. You've got a life here with us

.

” Afterward Ted went directly to an interview with a twentysomething magazine writer and mentioned what he'd just been told.

Ted said that writer told him, “âI gotta tell you, from the perspective of a lot of your fans, we'd be really bummed if you signed to a major label.' And initially I was like, âFuck you. That's not for you to decide.' But my other reaction was practical.” He now understood that the A&R guy feeding him those lines could well be gone in a few months, and Ted knew no one else at that label. And he realized something else: “They're not going to make me into a star. I was thirty-three or thirty-four, writing political pop songs. That's not the equation for hits.

And

I'm going to lose half my existing audience? That sounds like a loser of a move.” Ted's very smart on the challenges that middle-aged indie rockers faceâGoogle any recent interview he's given for proofâbut even he had to watch a generation of indie bands fail on major labels before reaching that conclusion.

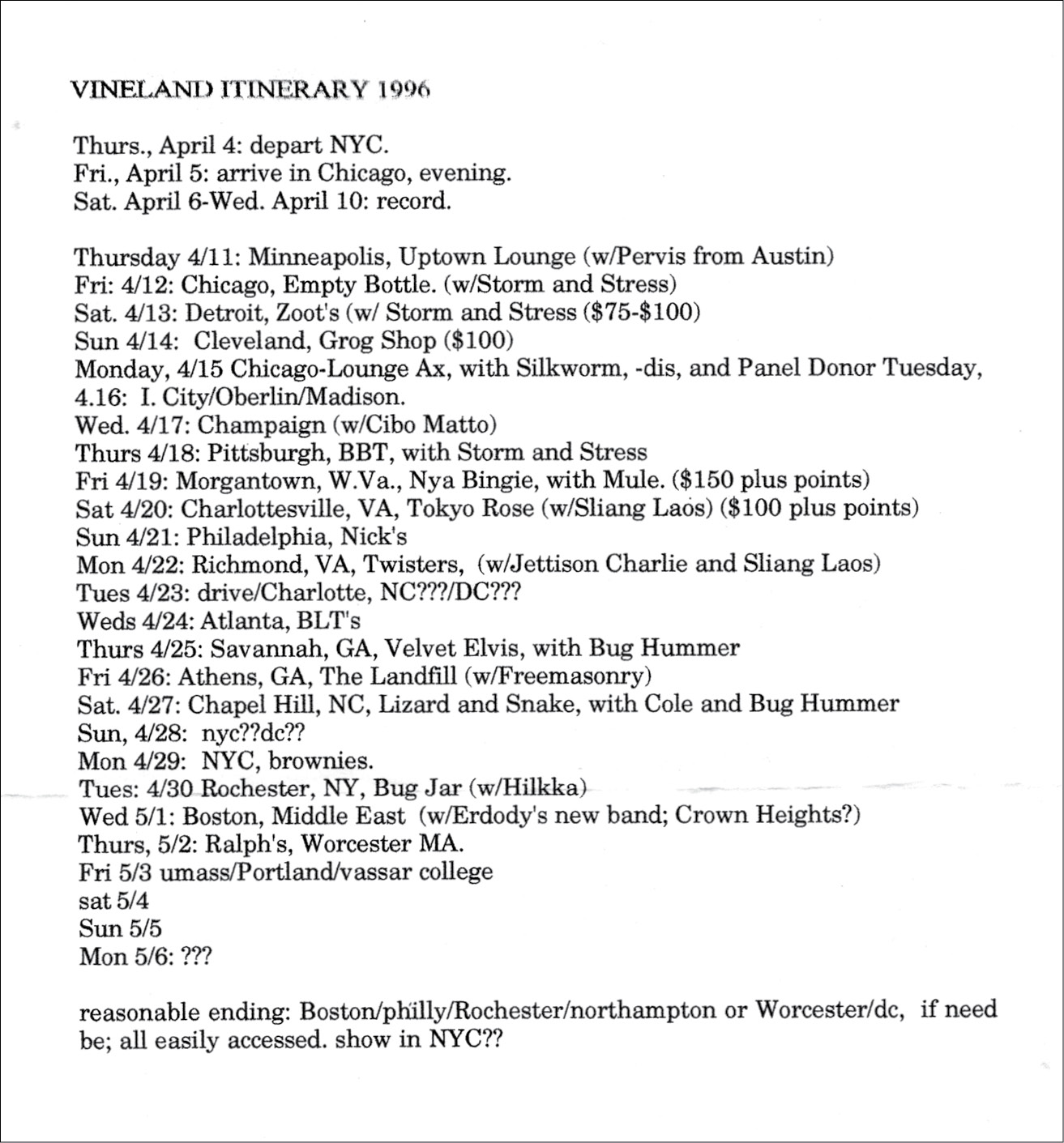

“Reasonable Ending”: This itinerary is a key prop for the next chapter.

That No One Likes

All bands fail.

âJoe Carducci, former co-owner of SST Records, author of

Rock and the Pop Narcotic

S

ome bands fail more spectacularly than others, and some fail very quietly, with no witnesses. But that failure doesn't feel quiet if you're in such a band and you find yourself confronting something tougher than the general outcastness of playing weird music: blank stares from those who actually

like

weird music. I don't mean “no widespread recognition

”

or “no pots full of money

.”

I mean

nothing

. No labels putting out your music. No fans coming to your shows. Because there are no fans.

If you've played in bands or spent any time within the social swirl surrounding music, you're familiar with the interested titter or two that typically greet a band's first few shows. That ripple of recognition is an amazing feeling when your band is new, and thrilling in its potential. At those first shows you come onstage and see the crowd moving toward you through the darkness. The stage lights are shining in your eyes, so you can't make out any faces, but you still sense the curiosity and eagerness in those bodies. The problem arises when it's three or four years later and your band has silently glided past new and kind of interesting and is now familiar and unbeloved. Your friends make excuses for not coming to your shows. You play to empty rooms, and the songs feel like cardboard, and you stand onstage atop unsteady legs, avoiding the eyes of anyone still watching. (Often all we had was conviction. When that went, what else was left?) But you still have to act like you believe, even though the evidence overwhelmingly indicates that no one else does, and that evidence gradually gnaws a hole in you. Once your band lands here, there's never a late-career comeback. There's no rock band equivalent to

The Rookie

. You're dead. The only question is when you'll realize it, too.

Peter Prescott was the youngest member of Mission of Burma, and at a very tender age he saw terms like “legendary” applied to his band. Nothing else he did in musicâhe played in Volcano Suns, Kustomized, and the Peer Group, among othersâmade such an impact, though, to be fair, not much else did. But he told me a very cool thing: “I'd be kind of bummed out if I didn't experience the more modest pleasure of being in a scrappy little messed-up band that thirty people in each city care about.” I'm grateful I experienced that, too. The problem is when that's your audience and most of them drift away.

I started Vineland in late 1991. Bitch Magnet had been a trio, so this would be a quartet: two guitars, very loud, songs built around alternate tunings and odd time signatures, very aggressive and, for lack of a better term, very rock. Riffs but no big major-key singalong choruses. By then the tyranny of vocals exhausted meâit still does sometimesâso in this band the singing would be understated, primarily spoken, fighting to be heard above the band. Having learned a lesson from getting booted out of Bitch Magnet, I made myself the key man: songwriter and singer. Since I was going to be so annoying about vocals, it made sense to just take the bullet. Also, the last thing you ever want to do is audition frontmen. David Lee Roth is great in Van Halen, but you do not want to live with that every day. (Evidently neither did they.)

Vineland lasted four and a half years. We released two singles and appeared on one Australian compilation and one Spanish compilation. If you, too, perceive something uniquely heartbreaking about the phrase “appeared on one Australian compilation and one Spanish compilation,” well, imagine

applying it

to your own band

. We also recorded two unreleased albumsâor, to be more precise, we recorded one album and then rerecorded much of it with a new rhythm section a year and a half later. We toured America three times, going as far west as Kansas City, as far east as Boston, as far north as Minneapolis, and as far south as Savannah. We played lots of weekend shows clustered in cities within a day's drive from New York. The bubble of mild enthusiasmâI mean this in highly relative termsâthat greeted us when we formed quickly dissipated. We didn't hear a whisper from anyone in Europe, that dream fulfiller of every loud indie band, no matter whom we barraged with tapes. At no point was any serious record label seriously interested, unless you count the nice postcard Jonathan Poneman of Sub Pop sent us. (I don't.) We went through four drummers and five bassists, even more if you count people who filled in for one or two shows. For the last few years I was the only original member. Our longestâand finalâtour, in 1996, lasted for a month. By then maybe fifteen or twenty people turned out for our hometown shows. In other cities, even less. Beyond the numbers, a dead feeling hung over those rooms. Twenty-five people in Cedar Rapids on a Tuesday night is fine, if you can feel their excitement, and you always can when it's there. On our best nights we'd draw forty or fifty souls, mostly friends and friends of friends, who'd shake my hand afterward and say something

tactful

, obligation weighing them down like a heavy coat. All the people who were there wished they weren't.

In the spring of 2013 Zack Lipez wrote an excellent piece for

The Talkhouse

newsletter, “I Threw a Show in My Heart and Nobody Came,” describing how he broke up his band, Freshkills, because, as he put it, “we had more ex-bassists than audience members.” Shortly afterward I met him in an apartment in lower Manhattan on a humid afternoon. Zack, who's now the singer of Publicist UK, is tall, with chunky round black glasses and pale skin and dyed black hair. A young thirty-seven when we met. (I might have guessed thirty-one.) Skinny but slightly potbellied, prickling with a nervous energy, like the frontman he is.

“The only time I almost broke down and cried was when I got the record sales back from our last album,” he told me. The tally: 336 physical copies and 27 digital tracks sold. (

Twenty-seven!

Jesus.) “Our drummer just said, âThere's no positive way of spinning this.'” There isn't, and here's how I know: Vineland self-releasedâby which I mean

I

self-releasedâa thousand copies of our second single in 1995. About four hundred of them remain entombed in a bedroom closet at my parents' house. Maybe there are more. I could count them, I guess, but to what degree must I quantify how many fans we didn't have? Meanwhile, those in search of sibling rivalries will likely find the following facts interesting: in the mid-nineties Sooyoung's band Seam toured America and Europe constantly and released well-received records on Touch and Go, while Orestes was making a living as the drummer for Walt Mink.

***

THE GUITARIST IN THAT FINAL VERSION OF VINELAND WAS

Fred Weaver, who first got in touch with me by sending a postcard to the band's post office box to offer us a show in State College, Pennsylvania. When I wrote back to say, hey, thanks, but the guitarist quit and we need to find another one before we can play any shows, he responded by saying that he wanted to try out, and he drove to New York from a small coal-country town in central Pennsylvania called Clearfield. He was twenty and shy, tall and thin, and barely needed to shave. But he could play, understood what I was trying to do, was insanely motivated, and, though I didn't need any more convincing, owned a van. He joined up and took on too muchâlike more or less singlehandedly soundproofing the practice space in our loftâwithout ever complaining. He also harbored his own ambitions to start a band. All of which meant tensions arose in difficult situations and in small quarters, and since we played in a struggling band and lived in a loft in which anywhere from four to six guys shared one bathroom, we spent plenty of time in both.

Our drummer was Jerry Fuchs, long before he became a legend and drummed for everyone from !!! and Maserati to MGMT and Turing Machine and, briefly, LCD Soundsystem, and longer before he became my closest friend to die young, in a stupid accident in a busted elevator at a party in Brooklyn in 2009. He dropped out of the University of Georgia and moved to Brooklyn to join the band in 1995, when he was a very young twenty, still sporting a bit of baby fat and a great deal of social awkwardness. He was also built like a pit bull: shorter than me but twice as wide, and god knows how much stronger. I'm susceptible to drummer-crushesâyou've probably noticedâand I totally developed one on him. I couldn't believe my luck: Vineland was already going nowhere, but we'd grabbed one of the best drummers I'd ever heard. Kylie Wright, a dark-haired, pale-skinned photographer, played bass, joining not long before that last tour. I was twenty-eight, and she was around my age, so we were the grown-ups. Kylie was Australian, but her accent emerged only if you got enough drinks into her. She had tiny, delicate hands, but she was a really strong bassist.

I had a generalized guilt about having hired Jerryâhe dropped out of college for

this

?âand I still feel as if I should apologize to Kylie, too. Because on that last Vineland tour I often thought we were touring like burglars, if burglars felt remorse. We played many cities with local bands we knew, all of whose hometown draws were much bigger than ours, since they lived there and nobody much liked us anywhere. But we'd get more than our share of the door, because we'd driven a long way and because our culture always took care of touring bands. Jerry was aghast at this practice, but we convinced him that it was either that or forgo food and gasoline. Or, rather, we didn't convince him and just did it anyway. Every night, when we got paid, I'd look down at the billsâa hundred and fifty bucks, a hundred bucks, often lessâmuttering thanks as I jammed them into a front pocket and quickly walked away, swallowing hard, feeling undeserving, and having taken advantage.

The plan that tour was that everyone would get a princely $10 per diem for food, but finances became so disastrous so quickly we couldn't manage even that. We were all broke, irregularly fed, and extremely crabby. At lousy fast-food joints I gobbled my burger and stared at anyone eating slowly, waiting for leftovers. There are people who live in a state of hunger. We weren't them, by any stretch: we had jobs back home and familiesâto paraphrase something the writer Cheryl Strayed once said, we were the impoverished elite, not the actual poor, and that's an enormous distinctionâand this was someplace we were merely visiting. But still, on this tour, we were measuring wealth by the french fry. Something I jotted in a journal during that tour:

When you're this broke, your relationship with food changes. If it's in front of you, you eat it, and anything on the table is fair game. You stuff yourself, to stave off hunger for as long as possible, then do it again. Eating less and lightly is for rich people.

I overweighted Chicago on the tour, because playing Chicago was more or less the entire point. Chicago was home to lots of friends and bands and studios and labels. Something could happen there. Or at least some people would show up. But I got greedy and booked us Friday at the Empty Bottle and the subsequent Monday at Lounge Ax. These were rival clubs, each suspicious and paranoid about the other, and they hated it when bands played both places. My move, once discovered, pissed everyone off and cannibalized our tiny draw. Silkworm headlined the show at Lounge Ax, so there was a decent crowd. Afterward Sue Miller, the owner and manager and a generally beloved person, kachinged the cash register behind the bar and handed me a few bills. “Here's some money for your band, Jon.”

Seventy-five dollars. In Chicago. The one city where I thought we'd do well.

I was very sensitive about money, mainly because I didn't have any, and though I told myself over and over that money didn't matter, being this broke so close to thirty was frightening. Around this time I co-wrote and performed a score for an NYU grad student production. My fee, for several weeks' rehearsals and a week's worth of shows, was five hundred bucks. No argument there: I'd agreed to that sum and was happy just getting paid. Except that I

wasn't

getting paid, and I really, really needed the money, so I visited a theater prof named Nance, the faculty adviser for the show and the closest thing to an authority to whom I could complain. An assistant milled about her office as I asked, politely, for my check. Nance told me to keep waiting for it. And, she suggested, if I

really

needed the money now, I could always borrow it from the directorâshe knew he and I were old friends.

Always question the judgment of anyone willing to be called

Nance

. I still regret not throwing a stapler, or saying something, or even staring for a long moment with a cocked eyebrow. Something. Anything

.

But I didn't, because I was ashamed, and shame can make you freeze. (And, worse, someone else witnessed that shame.) As I was ashamed when Sue handed me the few bills, and I found I couldn't refuse or complain. Charity once more. And had I heard a hint that we were being done a favor we could never call in again?

Here's some money for your band.

***

VINELAND'S ENDGAME HAPPENED DURING THE WANING

moon of that era in the nineties in which major labels were lunging spastically toward virtually any established indie band. Even though, by then, many signings had resulted in sales that were visible only with a microscope. Vineland or Freshkills numbers, albeit for giant entertainment corporations that expected six- or seven-figure sales. (The one record on Geffen by Hardvarkâits drummer was Bob Rising, who'd formerly played in Poster Children and Sooyoung's band Seamâsold 372 copies, according to Soundscan.) But there were still a few late fluke hits from bands we knew. Hum, from Champaign, was briefly all over the radio in 1995 with “Stars.” Hum primarily played a pedestrian version of the this-is-the-soft-part/NOW-THIS-IS-THE-LOUD-PART thing, and their drummer had a huge thing for Bitch Magnet. Vineland played a few shows with them, and the drummer invariably cornered me to ask incredibly picayune questions about Orestes's drum gear and technique. That year, I'd drive over the Williamsburg Bridge to go drink at Max Fish on a Friday or Saturday night, listening to the big FM rock station, and “Stars” would come on. The following Wednesday Vineland would play to a dozen people in a basement in the very preâ

Sex and the City

Meatpacking District. Hum's subsequent work went nowhere, but they still squeezed through one of the occasional wormholes in the musical universe and scored a hit big enough to sell a few hundred thousand records.