Your Face Tomorrow: Poison, Shadow, and Farewell (71 page)

Read Your Face Tomorrow: Poison, Shadow, and Farewell Online

Authors: Javier Marías,Margaret Jull Costa

Mrs. Berry's promised letter took more than two months to arrive. She apologized for the delay, but she'd had to take care of almost everything, even the recent memorial service, a ceremony which, in England, tends to take place sometime after the death. She was kind enough to send me a copy of the order of service, listing the hymns and readings. Wheeler hadn't been a religious man, she explained, but she had preferred to fall back on the rites of the Anglican church, because 'he always hated the improvised ceremonies people hold these days, the secular parodies that are so popular now' The service had taken place in the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Oxford, a church I remembered well; it was where Cardinal Newman had preached before his conversion. Bach had been played and Gilles, as well as Michel Corrette's gentle, ironic

Carillon des morts;

hymns had been sung; passages from Ecclesiasticus had been read ('. . . He will keep the sayings of the renowned men: and where subtil parables are, he will be there also. He will seek out the secrets of grave sentences ... he will travel through strange countries; for he hath tried the good and the evil among men. Many shall commend his understanding; and so long as the world endureth, it shall not be blotted out; his memorial shall not depart away, and his name shall live from generation to generation. If he die, he shall leave a greater name than a thousand: and if he live, he shall increase it'), as well as the Prologue from

La Celestina

in James Mabbe's 1605 translation and an extract from a book by a contemporary novelist of whom he was particularly fond; and his praises had been sung by some of his former university colleagues, among them Dewar the Inquisitor or the Hammer or the Butcher, whose eulogy had been particularly acute and moving. And this had all been arranged according to the very precise written instructions left by Wheeler himself.

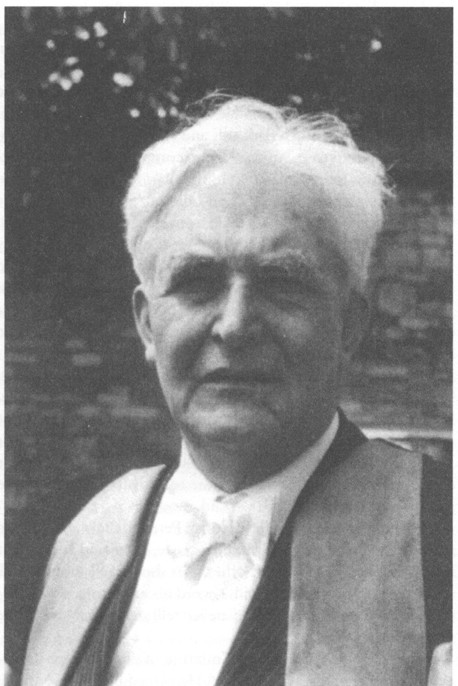

Mrs. Berry also enclosed a color photo of Peter taken some years before ('I thought you would like it as a keepsake,' she said). Now I have it framed in my study and I often look at it, so that the passing of time does not cause my memory of his face to grow dim and so that others might still see it. There he is, wearing the gown of a Doctor of Letters. 'It's made from

scarlet cloth with grey silk edging or facing, and the same on the sleeves,' Mrs. Berry explained. 'Sir Peter's gown had belonged to Dr. Dacre Balsdon, and the grey had faded somewhat, so that it looked more like a dirty blue or a greyish pink: it had probably been left out in the rain. I took the photo in Radcliffe Square on the day he received that degree. It's a shame he took off his mortarboard to pose for the picture.' There is, of course, no word in Spanish for the untranslatable 'mortarboard.' Underneath his gown Peter is wearing a dark suit and a white bow tie, an outfit which is referred to as 'subfusc' and is compulsory at certain ceremonies. And there he is now in my study, fixed forever on that far-off day, in a photo taken when I did not yet know him. The truth is that he changed very little from then until the end. I can recognize him perfectly when he looks at me with those slightly narrowed eyes, and you can clearly see the scar on the left-hand side of his chin. I never did ask how he got it. I remember that I hesitated over whether to ask him on that last Sunday, after lunch, when I was about to go to the station and get the train back to London and he accompanied me to the front door, leaning more heavily than ever on his stick. I noticed then that his legs were weaker than they had been on any other occasion, but they were doubtless capable of carrying him about the house and the garden and even up to his bedroom on the second floor. But he looked very tired, I thought, and I didn't want to make him talk much more, and so I chose to ask him something else, just one more thing before we said goodbye:

'Why did you tell me all this today, Peter? Believe me, I found it fascinating, and I'd love to know more, but I find it odd that, after years of knowing each other, you should tell me about all these things you've never said a word about before. And once you said to me: "One should never tell anyone anything," do you remember?'

Wheeler smiled at me with a mixture of slight, almost imperceptible melancholy and mischief. He placed both hands on his walking stick and said:

'It's true, Jacobo, you should never tell anyone anything . . .until you yourself are the past, until you reach the end. My end is fast approaching and already knocking insistently at the door. You need to begin to come to terms with weakness because there will come a day when it will catch up with you. And when that moment arrives, you have to decide whether something should be erased forever, as if it had never happened and never even had a place in the world, or whether you're going to give it a chance to . . .' He hesitated for a moment, looking for the right word and, not finding it, he made do with an approximation: '. . . to float. To allow someone else to investigate or recount or tell it. So that it won't necessarily be lost entirely. I'm not asking you to do anything, I assure you, to tell or not to tell. I'm not even sure I've done the right thing, that I've done what I wanted. At this late stage, I don't know what my desires are any more, or if I have any. It's odd, towards the end, one's will seems to become inhibited, to withdraw. As soon as you go through that door and walk away, I shall probably regret having told you. But I can be sure that Mrs. Berry, who knows most of what happened, will never say a word to anyone when I'm gone. With you I'm not so sure, though, and so I leave that up to you. I might prefer it if you kept silent, but, at the same time, it consoles me to think that with you my story might even . . .' He again sought some better word, but again could not find it: '. . . yes, that it might still float. And that's really all it comes down to, Jacobo, to floating.'

And I thought and continued to think on the train back to Paddington: 'He's chosen me to be his rim, the part that resists being removed and erased, that resists disappearing, the part that clings to the porcelain or the floor and is the hardest bit to get rid of. He doesn't even know if he wants me to take charge of cleaning it up—"the constitution of silence"—or would rather I didn't rub too hard, but left a shadow of a trace, an echo of an echo, a fragment of a circumference, a tiny curve, a vestige, an ashy remnant that can say: "I was here," or "I'm still here, therefore I must have been here before: you saw me then and you can see me now," and that will prevent others from saying: "No, that never occurred, never happened, it neither strode the world nor trod the earth, it never existed, never was.'"

Mrs. Berry also spoke in her letter about the drop of blood on the stairs. She couldn't have helped hearing part of our conversation as she bustled around in the kitchen and came and went, on that last Sunday when I visited them (the verb she used was 'overhear,' which implies that it was involuntary), and how Wheeler referred in passing to the stain as if it had been a figment of my imagination ('Just there, where you say you saw ...'). She felt bad about having lied to me at the time, she said, to have pretended to know nothing, perhaps to have made me doubt what I had seen. She asked me to forgive her. 'Sir Peter died of lung cancer,' she wrote. 'He knew deep down that he had it, but he preferred not to. There was no way he would go to the doctor and so I brought one, a friend of mine, to the house when it was already too late, when there was nothing to be done, and that doctor kept the diagnosis from him—after all, what was the point in telling him then?—but he confirmed it to me. Fortunately, he died very suddenly, from a massive pulmonary embolism, according to what the doctor told me afterwards. He didn't have to endure a long illness and he enjoyed a reasonable life right up until the end.' And when I read this, I remembered that the first time Wheeler had suffered one of his aphasic attacks in my presence—when he had been unable to come out with the silly word 'cushion'—I had asked him then if he'd consulted a doctor and he'd replied casually: 'No, no, it's not a physiological thing, I know that. It only lasts a moment, it's like a sudden withdrawal of my will. It's like a warning, a kind of prescience . . .' And when he didn't finish the sentence and I asked him what kind of prescience, he had both told me and not told me: 'Don't ask a question to which you already know the answer, Jacobo, it's not your style.'

'In fact, the only symptom, during almost the whole time he was ill,' Mrs. Berry went on, using a term doubtless learned from her medical friend, 'was the occasional hemoptoic expectoration, that is, coughing up blood.'—And I thought when I read that paragraph: 'So much of what affects and determines us is hidden.'—'This used to be quite involuntary and only happened when he coughed particularly hard, and sometimes he didn't even realize; remember, although he may not have seemed it, Sir Peter was very old. So although it's impossible to be sure, that might be what you found that night at the top of the first flight of stairs and that you took such pains to clean up. I'm very grateful to you, because that, of course, was my job. On a normal day, it would have been most unusual for me to miss something like that, but I was so busy that Saturday getting ready for the buffet supper, with all those people, and, if I remember rightly, you pointed to the wood, not the carpet, where it would have been much more visible. Anyway, on your last visit, when I heard Sir Peter telling you about his wife's blood at the top of that first flight of stairs, sixty years before and in another house, well, I was afraid you might think you'd had a supernatural experience, a vision, and I had to let you know about this other real possibility. I do hope you'll forgive my pretense at incredulity, but I couldn't, at the time, mention something that Sir Peter preferred not to acknowledge. Well, the truth is he chose not to do so right up until the last. Indeed, he died without knowing he was dying, he died without believing that he was. Lucky him.' And then I recalled two things I had heard Wheeler say in different contexts and on different occasions: 'Everything can be distorted, twisted, destroyed, erased, if, whether you know it or not, you've been sentenced already, and if you don't know, then you're utterly defenseless, lost.' And he had also stated or asserted: 'And so now no one wants to think about what they see or what is going on or what, deep down, they know, about what they already sense to be unstable and mutable, what might even be nothing, or what, in a sense, will not have been at all. No one is prepared, therefore, to know anything with certainty, because certainties have been eradicated, as if they were infected with the plague. And so it goes, and so the world goes.'

Yes, now I'm living in Madrid again, and here, too, everything points towards that, or so I believe. I've gone back to working with a former colleague, the financier Estevez, with whom I worked for a few years after my Oxford days, when I married Luisa. He no longer refers to himself as 'a go-getter' as when we first met, he's grown too important for such nominal vanities, he doesn't need them. I contacted him from London, to sound him out regarding job opportunities, given my imminent return: I had saved quite a lot, but could foresee a lot of expenses on my return to Madrid. And when I told him briefly over the phone what I had been up to, I noticed that he was impressed when I said I'd worked for MI6, even though I'd been employed by a strange unknown group in a building with no name, which never gets a mention in any book—so ethereal and so ghostly that it didn't even require its members to have British nationality or to swear an oath—and even though I couldn't give him any proof, but only tell him what I knew. Not that I wanted to give him too many details, and those I did were invented. Anyway, he took me on at once to help with his various projects and he trusts my judgment, especially about people. And so I do still interpret people, just for him, now and then, and given my previous experience—given my record—he always listens to me as if I were the oracle. Thanks to him I earn enough money to be able to pay for Luisa to have some botox treatment, if one day she should ever want to, or indeed anything else that might improve her appearance, if she ever starts to get obsessed, although I don't think she will, it's not in her nature. To me it looks as good as before I left, before I left my home for England, her appearance I mean. And what I didn't see for a long time—but which was seen by another in my absence—that, too, seems just as good. And when I say I don't live alone but half-alone, that's because I either take the children out or visit them almost daily, and on some afternoons Luisa comes to my apartment, leaving the kids with another babysitter, not the stern Polish Mercedes, who has married and set up on her own—she's apparently opened her own business.

This is how Luisa wants it, with each of us in our own apartment, which is perhaps why she has never said what I wanted her to say or write to me during my solitary and, subsequently, troubling time in London: 'Come, come, I was so wrong about you before. Sit down here beside me, here's your pillow which now bears not a trace, somehow I just couldn't see you clearly before. Come here. Come with me. There's no one else here, come back, my ghost has gone, you can take his place and dismiss his flesh. He has been changed into nothing and his time no longer advances. What was never happened. You can, I suppose, stay here forever.' No, she hasn't said that or anything like it, but she does say other occasionally disconcerting things; during our best or most passionate or happiest moments, when she comes to see me at home as she must have gone to see Custardoy over a period of many months, she says: 'Promise me that we'll always be like this, the way we are now, that we'll never again live together.' Perhaps she's right, perhaps that's the only way we can remain properly attentive and not take each other or our presence in each other's lives for granted.