Zero (2 page)

Authors: Charles Seife

The Greeks understood mathematics better than the Egyptians did; once they mastered the Egyptian art of geometry, Greek mathematicians quickly surpassed their teachers.

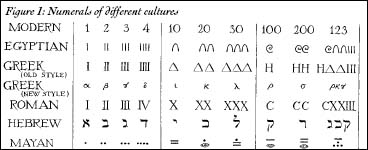

At first the Greek system of numbers was quite similar to the Egyptians'. Greeks also had a base-10 style of counting, and there was very little difference in the ways the two cultures wrote down their numbers. Instead of using pictures to represent numbers as the Egyptians did, the Greeks used letters. H (eta) stood for

hekaton

: 100. M (mu) stood for

myriori

: 10,000âthe myriad, the biggest grouping in the Greek system. They also had a symbol for five, indicating a mixed quinary-decimal system, but overall the Greek and Egyptian systems of writing numbers were almost identicalâfor a time. Unlike the Egyptians, the Greeks outgrew this primitive way of writing numbers and developed a more sophisticated system.

Instead of using two strokes to represent 2, or three Hs to represent 300 as the Egyptian style of counting did, a newer Greek system of writing, appearing before 500

BC

, had distinct letters for 2, 3, 300, and many other numbers (Figure 1). In this way the Greeks avoided repeated letters. For instance, writing the number 87 in the Egyptian system would require 15 symbols: eight heels and seven vertical marks. The new Greek system would need only two symbols: ? for 80, and for 7. (The Roman system, which supplanted Greek numbers, was a step backward toward the less sophisticated Egyptian system. The Roman 87, LXXXVII, requires seven symbols, with several repeats.)

for 7. (The Roman system, which supplanted Greek numbers, was a step backward toward the less sophisticated Egyptian system. The Roman 87, LXXXVII, requires seven symbols, with several repeats.)

Though the Greek number system was more sophisticated than the Egyptian system, it was not the most advanced way of writing numbers in the ancient world. That title was held by another Eastern invention: the Babylonian style of counting. And thanks to this system, zero finally appeared in the East, in the Fertile Crescent of present-day Iraq.

At first glance the Babylonian system seems perverse. For one thing the system is

sexagesimal

âbased on the number 60. This is an odd-looking choice, especially since most human societies chose 5, 10, or 20 as their base number. Also, the Babylonians used only two marks to represent their numbers: a wedge that represented 1 and a double wedge that represented 10. Groups of these marks, arranged in clumps that summed to 59 or less, were the basic symbols of the counting system, just as the Greek system was based on letters and the Egyptian system was based on pictures. But the really odd feature of the Babylonian system was that, instead of having a different symbol for each number like the Egyptian and Greek systems, each Babylonian symbol could represent a multitude of different numbers. A single wedge, for instance, could stand for 1; 60; 3,600; or countless others.

Figure 1: Numerals of different cultures

As strange as this system seems to modern eyes, it made perfect sense to ancient peoples. It was the Bronze Age equivalent of computer code. The Babylonians, like many different cultures, had invented machines that helped them count. The most famous was the abacus. Known as the

soroban

in Japan, the

suan-pan

in China, the

s'choty

in Russia, the

coulba

in Turkey, the

choreb

in Armenia, and by a variety of other names in different cultures, the abacus relies upon sliding stones to keep track of amounts. (The words

calculate, calculus,

and

calcium

all come from the Latin word for pebble: calculus.)

Adding numbers on an abacus is as simple as moving the stones up and down. Stones in different columns have different values, and by manipulating them a skilled user can add large numbers with great speed. When a calculation is complete, all the user has to do is look at the final position of the stones and translate that into a numberâa pretty straightforward operation.

The Babylonian system of numbering was like an abacus inscribed symbolically onto a clay tablet. Each grouping of symbols represented a certain number of stones that had been moved on the abacus, and like each column of the abacus, each grouping had a different value, depending on its position. In this way the Babylonian system was not so different from the system we use today. Each 1 in the number 111 stands for a different value; from right to left, they stand for “one,” “ten,” and “one hundred,” respectively. Similarly, the symbol in

in stood for “one,” “sixty,” or “thirty-six hundred” in the three different positions. It was just like an abacus, except for one problem. How would a Babylonian write the number 60? The number 1 was easy to write:

stood for “one,” “sixty,” or “thirty-six hundred” in the three different positions. It was just like an abacus, except for one problem. How would a Babylonian write the number 60? The number 1 was easy to write: . Unfortunately, 60 was also written as

. Unfortunately, 60 was also written as ; the only difference was that

; the only difference was that was in the second position rather than the first. With the abacus it's easy to tell which number is represented. A single stone in the first column is easy to distinguish from a single stone in the second column. The same isn't true for writing. The Babylonians had no way to denote which column a written symbol was in;

was in the second position rather than the first. With the abacus it's easy to tell which number is represented. A single stone in the first column is easy to distinguish from a single stone in the second column. The same isn't true for writing. The Babylonians had no way to denote which column a written symbol was in; could represent 1, 60, or 3,600. It got worse when they mixed numbers. The symbol

could represent 1, 60, or 3,600. It got worse when they mixed numbers. The symbol could mean 61; 3,601; 3,660; or even greater values.

could mean 61; 3,601; 3,660; or even greater values.