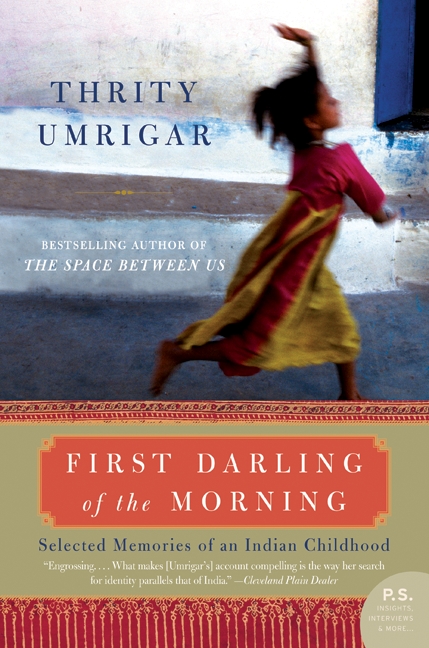

Authors: Unknown

of the

Morning

Selected Memories of an Indian

Childhood - THRITY UMRIGAR

To JBU, HJU and ETK

With endless love and infinite

gratitude

I

AM OF THAT GENERATION of middle-class,

westernized, citified Indian kids who know the words to Do-Re-Me

better than the national anthem.

The Sound of Music

is our

call to arms and Julie Andrews our Pied Piper. It is 1967âHollywood

movies always come to India a year or two after their American

releaseâand the alleys and homes of Bombay are suddenly alive

with the sound of music. No matter that the movie has reached us over

a year after it is a hit all over the Western world. All the piano

teachers in Bombay are teaching their beginner students how to plunk

Do-Re-Me until it seems as if every middle-class Parsi household with

a piano emits only one tune.

I am six years old and suffer from an only child's

fantasy of what life with siblings would be like.

The Sound of

Music

gives flight to that fantasy, provides it with shape and

colour. The laughter, the camaraderie, the teasing, the

close-knittedness of the Von Trapp family ensnares me, forever

setting my standard of what a perfect family should be. The Von

Trapps are as light and sunny as my family is dark; they whistle and

sing while the adults in my household are moody and silent; the

children are as shiny and healthy and robust as I am puny and sickly

and awkward. To see those seven children up on that large screen,

standing in descending order of age and height, is to see heaven

itself. My heart bursts with joy and longing; I want to leave my seat

and crawl into the screen and into the warm, welcoming arms of Maria.

Take me in, I want to say, give me some time and I will be as witty

and playful and musical as the rest of you.

I have already seen the movie once but now I want

to go again. Dad and his brother Pesi, whom I call Babu, decide that

the entire family should go see the movie together. As always, my

reclusive aunt, Mehroo, refuses to accompany us. âCome on,

Mehroo, it's a nice, wholesome family movie. You will enjoy

it,' says my aunt Freny, Babu's wife, but to no avail.

Pappaji, my grandfather, has recently had a heart attack and Mehroo

refuses to leave him home alone even though he is perfectly mobile.

Mehroo is my dad's unmarried sister who

lives with us. The oldest of my dad's two siblings, her

childhood ended on the day her mother died. Mehroo was then eleven.

Not only were there two younger brothers to raise (my dad, the

youngest, was only four) but there was a father to protect from the

razor's edge of his own grief. She took over the family duties

as though she had been born for that role. Her father was a kindly

man but he was so wrapped up in his own sorrow that he failed to

notice the sad look come into his daughter's eyes, a sadness

that would stalk her for the rest of her life. I suppose that from

her father's lasting grief and devotion to his dead wife, from

his endless mourning, Mehroo formed her own notions of what love

should be. And what family became for her was a profession, a job, a

hobby, an avocation. Family was all. Outside of its protective

borders lay the troubled world, full of deceit and deceptions and

broken promises and betrayals. It was an as-tonishingly limited

worldview but it made her irreplaceable within our family structure.

Mehroo's love for me is legendary throughout

the neighbourhood. So are her eccentricities.

She won't go to the moviesâan amazing

feat in a movie-crazy family.

She won't buy new clothes for herself. If

someone in the family buys her material for a dress, she will save it

for years before she will take it to the tailor.

She uses the same comb even after three of its

teeth fall out, until my father finally throws it away in a pique of

anger. But she frequently slips money to me when I leave for school.

She is a vegetarian in a household where chicken

and meat, being as expensive as they are, are treats. If a spoon

that's been in the chicken curry accidentally touches her

potato curry, she will not eat it. And yet, she will cook meat for

the rest of us.

She will eat food cold from the fridge without

warming it up, although she will spend hours in the kitchen cooking

for the family.

She refuses to pose for pictures, covering her

face with her hands to avoid the camera. When she is compelled (by

me, when I'm older) to be photographed, she refuses to smile.

Every picture of her shows a serious, unsmiling

woman. In some of them, her lips even curl downward.

She is miserly, cheap, teary, sentimental,

thin-skinned, fiercely loyal, eccentric, indifferent to the world

outside her family and devoted to her loved ones.

you solve a problem like Mehroo?

My cousin, Roshan, once mutters that if Mehroo was

the next door neighbour, she wouldn't like her very much. The

remark tears me up. I fancy that I understand Mehroo, in all of her

contradictions, better than anyone else; that somehow I have X-ray

vision that allows me access to the innermost chamber of her warm and

soft heart. There is something elemental and primitive about my love

for Mehroo and when I think of her, I think of her in animalistic

termsâas a dog or a horse or a giraffe or a zebra, animals with

sorrowful, kind eyes.

Now I decide that the movie situation calls for my

brand of lethal, irresistible charm. âPlease, Mehroofui, please

come,' I beg her. âJust once, please, for my sake. I love

this movie the best of all. You will, too, I promise.'

She shakes her head no, her brown eyes looking at

me pleadingly. I sing a few lines from the movie, hoping to entice

her that way. But she will not budge.

Pappaji finally erupts. âJa nee,' he

says. âBachha ne dookhi karech. Making my little one unhappy

like this. Nothing is going to happen to me in one evening. Treating

me as if I'm a six-year-old schoolboy in half pants.'

It works. Mehroo comes and there we are on a

Saturday evening, sitting in the comfortable seats at Regal Cinema,

waiting for the red velvet curtain to rise and for Julie Andrews to

burst forth onto the screen in full-throated glory. We sit in a long

row: myself, Mehroo, Roshan and her parents, Freny and Babu, and my

mom and dad. I can barely stay still on my seat because of my

excitement. Even before the curtain has lifted, the magic, the

promise of

The Sound of Music

has come true. Here I am with my

own family, all of us looking as close and loving and happy as the

Von Trapp family. For months now, I have had this recurrent fantasy

of my entire family lying together on a big bed, all of us happy and

cosy, and turning to each other for shelter and warmth, as if the bed

was a ship tossing on tumultuous waters. All of us under the same

roof, together. This is the closest I've come to duplicating

that feeling outside of dreams and my heart throbs with love and

happiness. I feel swollen and large, as if I could elongate my hands

to touch the back of their seats and embrace the long row of family

members.

At this moment, I have no prescience of how the

currents of life will pull me away from that idealized dream of

family; of how long and far I will travel and how my travels will put

that dream forever out of my reach. No idea then of how I will

unwittingly be yet another loss in my family's chronicle of

losses. There is nothing in this carefree moment to tell me that I

will someday trade love for freedom, that I will turn my back on

Mehroo's example of self-sacrifice and devotion to family, and

instead choose self-preservation and independence. That I will build

my life and dreams on the back of their sacrifices.

Yes, I will return to them over and over again but

it will never be the same. I will come as a visitor and a tourist,

will return with stories to show Mehroo the stamps on my body from

the different places I have travelled but she will not be impressed.

For they will only serve to remind her of what is missing from my

lifeâthe rootedness of home. And Mehroo's questioning

eyes will follow me and the bewilderment in them will never diminish,

will forever be the lump in my throat.

But before there is all that, there is this

heavenly night at Regal Cinema. For this glorious moment, here we all

are at the movies, just like any normal family. Mehroo's warm

hand is in my lap and when I sneak a peek at her in the dark, she is

smiling. Everybody seems to realize that this is a special occasion,

with Mehroo accompanying us, and I feel the unspoken admiration of

all the adults for having been the catalyst for this outing. During

the intermission, Dad is characteristically generous and comes back

loaded with chicken rolls, Sindhi samosas and bottles of Gold Spot

and Coke.

Munching my chicken roll, singing along to the

songs as familiar to me as my name, I am struck by a beam of pure

happiness, a drop of golden sun. When Christopher Plummer sings the

line, âBless my homeland forever,' my hair stands up, as

it always does. When Ralph betrays the Von Trapps in the abbey, I

turn to assure Mehroo, âDon't worry. Nothing bad

happens.' She nods and squeezes my hand.

For one blissful evening, I am no longer envious

of the Von Trapp family. I leave the theatre that evening, knowing my

place in the world. I am a member of a family that is large and

loving and goes to the movies together. I am loved by a sad-eyed

woman who loves me above all else. I am the daughter of a father who

buys everybody Gold Spot and chicken rolls and a mother who held my

hand tight on our way to the movie theatre. I am the reason they are

all here, I am the one who has drawn Mehroo out of the house, I am

the one responsible for the smiles on their faces.

I step out of the theatre and into the world

feeling fluid and grand and irresistible.

Dad has enjoyed the family outing to the movies so

much that a few days later, he suggests a picnic. I am thrilled. I

have never been on a family picnic before. But before he can announce

his idea at dinner, mom pulls him into their room for a quick talk.

He emerges a few minutes later and tells me that on second thoughts,

he'd like it if just the three of usâmom, myself and

heâwent on the picnic together. I am surprised but am too

excited at the prospect to disagree or complain.

We are to go to Hanging Gardens. We plan the

picnic for days, with dad even promising to skip his usual practice

of spending most of Sunday morning and afternoon at the factory.

Either Babu or dad visit the factory everyday,

even on the days the machines aren't humming. The ritual is as

much a gesture of respect and superstition as it is demanded by

necessity. At home, Mehroo chides me if I accidentally refer to the

business as being closed for the day. âThe factory is never

closed,' she says. âJust say, “We're not

there for one day.”' But on the day of the picnic, dad

leaves for the factory at eight a.m. and is back home by ten, to pick

up me and my mom. He honks the horn but as always, mom is running

late and I lean over the railing of the balcony to tell him that she

needs another half hour. Even from two floors up, I can sense his

irritation. âOkay, I'll come up then,' he says.

By the time we leave, it's almost eleven and

dad is in a bad mood. âHow much I told you yesterday about

wanting to leave on time. Now what's the use of being out in

the noonday sun,' he mutters. âOur skins will be black as

coal in an hour.' Like many light-skinned Parsis, my dad

treasures and protects his lemon-coloured skin as if it is the

Kohinoor diamond. While walking, he will instinctively duck for the

shade and when driving with the windows rolled down, he puts a yellow

duster cloth over his right hand as it rests on the window, to

protect it from the sun's angry rays.