100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (20 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

53. 4 x 30 x 2

On October 1, 1977, one day before the end of the regular season, Dusty Baker drove a pitch within a few feet of the right-field fence.

“I thought I had it,” Baker told Ross Newhan of the

Los Angeles Times

. “I'll be taking another shot tomorrow. It's definitely been on my mind and has probably affected my swing. I'm going to try and think in terms of line drives tomorrow. [But] being sharp for Philadelphia [and the 1977 NLCS] is more important than hitting the 30

th

.”

Baker was probably right to temper his expectations, at least publicly. On the final day of the season, the Dodgers were facing a tormentor in Houston Astros pitcher James Rodney Richard. In 24 career starts against Los Angeles, Richard pitched at least nine innings while allowing one run or less 10 times, and his career ERA against the Dodgers in 208 innings was 1.86.

But in the sixth inning of the final game, in his penultimate at-bat, Baker cleared the left-center field corner of the Dodgers bleachers, joining Steve Garvey (33), Reggie Smith (32), and Ron Cey (30) to give the Dodgers the first foursome of players in baseball history with 30 or more home runs.

And lest you think Baker didn't care, he told Newhan the next day that hitting the homer made him “the happiest man on Earth.”

It's hard to know what was more unlikelyâthat it took baseball until 1977 to achieve this feat, or that these four were the ones to do it. Subsequently, in home-run-happier times, several teams would repeat the deedâincluding the Dodgers 20 years later with Mike Piazza (40), Eric Karros (31), Todd Zeile (31), and, by hitting two on the second-to-last day of the season, Raul Mondesi (30).

But this crew? Once in his life, Smith had hit 30 home runs. Cey's career high in homers was 25. Both Baker's and Garvey's career high in homers was 21, and the year before, they had

combined

for 17.

But setting the stage for the accomplishment in his first full season as Dodgers manager, Lasorda urged Garvey before the 1977 season to try to aim for the fences, saying that “the home run is the most important part of the offense.” Garvey agreed to try, even though, according to Bob Oates of the

Times

, he disagreed with the premise.

Entering the season thinking that 20 was a realistic goal, Garvey reached that number before the All-Star break thanks to a 12-homer June. He hit his 30

th

on September 14. Cey got off to a ferociously hot start in April, hitting nine home runs and driving in 29 runs (a team record at the time) before reaching 30 on September 18, five innings before Smith did the same. All members of the Dodger quartet homered in that game, in fact.

But it was Baker who completed the most remarkable journey, a year after he hit only four home runs in a miserable first Dodgers season following his acquisition from Atlanta. As late as September 2, Baker was stuck on 20 homers for the year, reinforcing how unlikely it was for the Dodgers to complete this task. But Baker homered in seven of his next 11 games to get within striking distance before hitting his 29

th

on September 25. Then came 5

1/2

agonizing days before finally came No. 30.

“The only thing I told him,” Tommy Lasorda related to Newhan, “was that the Lord didn't intend to strand him on 29.”

Â

Â

Â

54. 1941: Three Strikes, You're Not Out

On January 22, 1857, 11 years and four months after Alexander Cartwright published a set of

Rules & Regulations of the Recently Invented Game of Base Ball

, a convention was held in New York to entertain revisions. There, according to 19cBaseball.com, it was decided that if a batter swung at a third strike that was not caught on the fly or on the first bounce, he could attempt to “make his first,” that is, run to first base before the catcher threw him out.

Those gents in the Civil War era could have fairly decided that, regardless of the disposition of the ball, a swing and a miss for a third strike was an out the moment the bat cut its arc through the plane of home plate. Instead, this baseball congress sought a more emphatic resolution, setting the stage, more than 84 years later, for the most memorable pitch in the first half of 20

th

-century Dodgers history.

By 1941, it had been 21 years since the Dodgers won the NL pennant; it had been nearly that long since they had even won as many as 90 games. With five games to go in the '41 season, they led the NL, but their margin over the St. Louis Cardinals was down to one game. However, a three-game winning streak, two by shutout, clinched the flag for Brooklyn and presented an opportunity for the Flatbush fans to celebrate their first World Series title.

On the first day of October in '41, that team from the Bronx hosted the Dodgers in their first World Series game ever against each other. Joe DiMaggio's crew won that inaugural contest 3â2, but Brooklyn tied the Series the next day with Dodger catcher Mickey Owen knocking a key RBI single in the fifth inning. After a day off, the reunion at Ebbets Field for Game 3 found the tightly matched squads scoreless into the eighth.

Dodgers righty Hugh Casey, who had just entered the game in relief, allowed a single to Red Rolfe before inducing a grounder to first from Tommy Henrich. As baseball writer Rob Neyer notes, Casey failed to cover first base, allowing Henrich to reach. Joe DiMaggio and Charlie Keller followed with RBI singles, with Henrich's run the difference as the Yankees held on for a 2â1 victory.

Game 4 found the Dodgers down by a 3â0 score before they rallied with two runs in the fourth and two in the fifth to take a 4â3 lead. Meanwhile, Casey was redeeming himself. As the Brooklyn offense went silent, Casey retired 12 of the next 14 batters. There was one batter to go, an ever-so-appropriate one: Henrich. Time to turn the tables.

On a full count pitch, Henrich swungâand missed. For a split second, a Game 4 victory dipped into the small space between Henrich's bat and Owen's glove.

“Casey had two kinds of curveballs,” Owen recalled in a 1988 interview alongside Henrich with Dave Anderson of the

New York Times

. “One was an overhand curve that broke big. The other one was like a slider, it broke sharp and quick. But we had the same sign for either one. He just threw whichever one was working best. When we got to 3 and 2 on Tommy, I called for the curveball. I was looking for the quick curve he had been throwing all along. But he threw the overhand curve, and it really broke big, in and down. Tommy missed it by six inches.”

Added Henrich: “As soon as I missed it, I looked around to see where the ball was. It fooled me so much, I figured maybe it fooled Mickey, too. And it did.”

The ball found its way to the backstop, and once more Henrich had sneaked onto first base. And a flood like Brooklyn had never laid eyes on before rushed through.

“I couldn't believe what happened; none of us could,” Owen said. “Then Joe DiMaggio hit a fastball, a screaming line drive over Pee Wee Reese's head into left field, then Charlie Keller hit a quick curve high off the right-field screen.”

DiMaggio's hit was a single; Keller's a double.

“That was a soft screen above that angled wall,” Henrich said. “The ball came straight down off that soft screen, hit the wall, bounced up in the air to give DiMaggio another two seconds and he slid across with the go-ahead run.”

“That was as good a play,” Owen said, “as Enos Slaughter scoring from first base for the Cardinals in the 1946 Series.”

After a Bill Dickey walk, a two-run double by Joe Gordon added two more runs to pad the lead 7â4. The Dodgers went down meekly in the bottom of the ninth, then mustered only a single run in a 3â1 Game 5 loss that ended the Series. It was this defeat that prompted the legendary

Brooklyn Eagle

headline, “Wait 'Til Next Year,” a mantra that would hang over Brooklyn for the next 14.

It's worth remembering that in the immediate aftermath of the defeat in '41, as Richard Goldstein recalled in his 2005 obituary for Owen, Brooklyn forgave. “I got about 4,000 wires and letters,” Owen said in an interview with W. C. Heinz for the

Saturday Evening Post

on the 25

th

anniversary of his error (in that era, those plays were not scored as passed balls). “I had offers of jobs and proposals of marriage. Some girls sent their pictures in bathing suits, and my wife tore them up.”

Decades after the pitch, historians have debated whether Casey really threw a curveball or whether, as many came to speculate, it was a spitballâan illegal pitch that brought Casey and the Dodgers what they deserved. But the conjecture might just as easily be spent on those men in 1857, and why they couldn't be satisfied that a swing and a miss on strike three could result in the batter being out. They could have done their Brooklyn neighbors a huge favor.

Â

Â

The First Playoff

Four years after Brooklyn's gut-wrenching loss of the 1942 NL pennant to St. Louis, the two teamsâBranch Rickey's former and current organizationsâwere at it again. Once more, the Dodgers had the lead for most of the seasonâthough it was a narrow oneâbefore a hard-charging Cardinals squad passed them. This time, however, the Cardinals couldn't put the Dodgers away quite so easily, losing three of their final four games, and for the first time since the NL was founded in 1876, the scheduled regular season had ended in a tie.

That set up a best-of-three playoff. A coin toss determined that St. Louis would host the first game, with Brooklyn being the home team for the second and third, if necessary. Turns out, Game 3 wasn't necessary. St. Louis scored three runs in the first three innings off Ralph Branca to give pitcher Howie Pollet all he would need for a complete-game 4â2 victory in the first contest. Two days later, the Dodgers were held hitless from the second inning through the eighth and fell behind 8â1 heading into the bottom of the ninth, then nearly staged a comeback that would have dwarfed 1951 or 1962. They scored three runs and loaded the bases with one out, but potential tying runs Eddie Stanky and Howie Schultz struck out to finally end Brooklyn's season.

55. Branch Rickey

It took a Branch Rickey to push integration forward in major league baseball. If Jackie Robinson was Chuck Yeager (the man to bust the sound barrier), then Rickey was the aircraft engineer whose unique combination of idealism and pragmatism put Robinson in position to soar.

Integration was not Branch Rickey's life's work. Fundamentally, he was a man of religionâtwo religions, really, because baseball stood along side his faith, and God was in the details in both. He lived and breathed the sport meticulously as a player, as a manager, and ultimately as an executiveâexcept on Sundays when he would piously shut it out. But though it was not as much of a preoccupation, he had an instinctive conviction about racial equality at a time such beliefs could not be taken for granted. There is a story mythical in its drama but true at its core: Coaching Ohio Wesleyan's baseball team, Rickey checked into a hotel on a road trip to Notre Dame, but his black catcher Charles Thomas was denied a room. Rickey entered to find Thomas sobbing and tearing at his own skin. Thomas ended up sleeping on a cot in Rickey's room. The experience never left Rickey; indeed, according to biographer Lee Lowenfish, Rickey and Thomas remained friends for life.

This incident happened more than four decades before Rickey met Jackie Robinson. Rickey made his name as a remarkably savvy general manager, building a pioneering farm system for the St. Louis Cardinals organization that helped make them the envy of any team that didn't have Babe Ruthâthe Cards won five NL pennants and three World Series in nine seasons. As historian Steven Goldman notes, Rickey started to pursue integration while with St. Louis, but found the opposition too overwhelming. Coming to the Dodgers in 1942, however, he lost none of his thirst for success and innovation. When the opportunity finally came to marry his morality with his work, he calculated exactly how he would succeed.

“In 1945, the New York state legislature passed the Quinn-Ives Act, a ban on discrimination in hiring,” Jonathan Eig wrote in

Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson's First Game

. “The same year, New York City's mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia, appointed a commission to investigate discrimination in hiring and appointed the sociologist Dan Dodson chairman. When Dodson turned his investigation to baseball and interviewed Branch Rickey, the Dodger boss was thrilled. He believed the public pressure and the commission's investigation would make it easier for him to integrate the team, and he quickly shared the details of his secret plan with Dodson. What's more, he asked Dodson for his help. Rickey told the sociologist he wanted to learn the politics and psychology of integration. He wanted to study the track records of institutions that had already integrated. He also wanted Dodson to help him stall. With a little more time, Rickey knew, he would have the chance to corner the market on black players, select just the right black man to break the color line, and prepare his white players for the new man's arrival. Dodson, thoroughly charmed, agreed to do whatever Rickey asked of him.”

Â

Â

Â

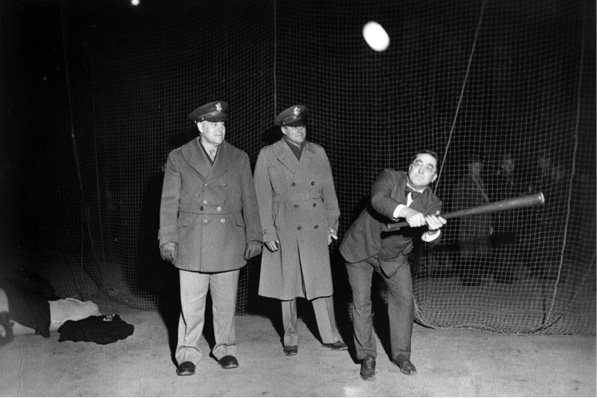

Dodgers president Branch Rickey swings a bat at West Point during Dodgers spring training at Bear Mountain, New York, circa 1943.

Photo by Barney Stein. All rights reserved.

Â

And so began the final steps that led Rickey to invite Robinson to his office on August 28, 1945, where they had perhaps the most important baseball meeting since the sport was born.

“Thus was born one of baseball's favorite legends,” writes Eig. “But in one important way, the accounts are misleading. Rickey didn't want Robinson for his ability to turn the other cheek. Had Rickey wanted a pacifist, he might have selected any one of half a dozen men with milder constitutions than Jack Roosevelt Robinson's.

“Rickey wanted an angry black man. He wanted someone big enough and strong enough to intimidate, and someone intelligent enough to understand the historic nature of his role. Perhaps he even wanted a dark-skinned man whose presence would be more strongly felt, more plainly obvious, although on this point Rickey was uncharacteristically silent. Clearly, the Dodger boss sought a man who would not just raise the issue of equal rights but would press it.

“It is testament to Rickey's sophistication and foresight that he chose a ballplayer who would become a symbol of strength rather than assimilation.”

Rickey was not a beloved figure. Many thought him pompous and beyond self-righteous. And the man who made it a mantra to trade a player a year too early rather than a year too late would alienate his fan base more than once. “When he arrived in Brooklyn and dealt the beloved Dolph Camilli to the hated Giants,” Eig comments, “it was indisputably the right move, but it infuriated fans, who hung Rickey in effigy from Brooklyn's Borough Hall.” But the man had nothing less than the courage of his convictions, and in his case, that was plainly significant, even long after integration was complete.

“For Robinson,” wrote Arnold Rampersad in

Jackie Robinson: A Biography

, “absorbing Rickey's death [in 1965] was a trial to compare to his 1947 ordeal: âI tried to prepare myself emotionally the same way I had for that first year.' His deep feeling for Rickey, Jack made clear, was only in part owing to the fact that Rickey had chosen him to be the first black player. Far more, he loved Rickey because Rickey had been loyal to him. He had been loyal during their four tumultuous years in the Dodger organization, but, more important to Jack, loyal when the cheering had died down, and especially after Jack retired from the game.”

Â

Â

Â