100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (23 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

63. Hercules

Charles Ebbets' middle name was Hercules, befitting a man who undertook prodigious labors in the big leagues. He had formidable ideas and great passions: He loved money, baseball, and Brooklyn, and though those devotions sometimes clashed titanically, they also gave birth to the Dodgers of the 20

th

century.

Born in 1859, at the end of the decade in which baseball in Brooklyn came to life, Ebbets made careers for himself in architecture, publishing, and politics but found his true calling in a job with the local ballclub in 1892. Understand that whatever zeal for the Dodgers you might ante up, Ebbets could probably see you and raise youâat least as far as trying to build up the overall organization. At first, he worked mainly in accounting and sales, but there were few tasks he wasn't compelled to pursue, including manager. Often accepting stock in the franchise as compensation, Ebbets rose to become club president in 1898.

From that point on, Ebbets was frequently mortgaging his entire financial well-being to fulfill his Brooklyn fantasies. He entered into a syndicate agreement with Baltimore, a popular method of the time that allowed one franchise to plunder another for talent, and won pennants in 1899 and 1900. He emptied his bank account to buy out minority owner Ferdinand Abell in 1902, according to John Saccoman's biographical sketch of Ebbets at the SABR Biography Project, and soon borrowed even more money so he could become majority owner. As if that weren't enough, Ebbets then prioritized the building of a state-of-the-art ballpark, which stretched his financial situation even further.

Not surprisingly, as Glenn Stout points out in

The Dodgers

, this made Ebbets less than generous with player payroll, allowing the newly forming American League to make off with many of his players to an extent that undermined his end-of-the-century Baltimore talent heist and sapped the on-field product in Brooklyn for years to come. And, of course, for all the financial deep-sea diving he took, for all the aggressive ticket pricing he instituted (including raising World Series grandstand tickets to a record $5 in 1916), for all his ambitions regarding the ballpark that would eventually be named for him, he couldn't muster the resources to create a facility that would stand the test of time. But that didn't stop the borough of Brooklyn from finding a special connection with the team in large part through his efforts.

Ebbets passed away in April 1925âdestitute neither in money nor spirit. “The Dodgers were scheduled to open a three-game series against the Giants at Ebbets Field later that day,” Saccoman writes. “âCharlie wouldn't want anybody to miss a Giant-Brooklyn series just because he died,' said Wilbert Robinson. The game went on, with the crowd standing for a moment of silence beforehand and both teams' players wearing black mourning bands on the left sleeves of their uniforms. NL president John Heydler ordered all NL games postponed on the day of the funeral, which was attended by most of the league's magnates.”

At the funeral, acting team president Ed McKeever caught pneumonia and died days later, setting the stage for the next chapter of Brooklyn history. Replacing Ebbets would be a Herculean task.

Â

Â

Â

64. Wes Parker and the Cycle

Ritual is a part of sports that can sometimes be simultaneously soothing and annoying. For the Dodgers, this used to be illustrated by “The Ballad of Wes Parker.”

Any timeâ

every

timeâa Dodger player would get three different types of hits in a game, the broadcaster of the moment would point out that the player's chance to become the first Dodger to hit for the cycle since Parker did so on May 7, 1970. The historical anecdote pushed the limit of diminishing returns; many Dodgers fans eventually learned it by rote like their times tables or their ATM code.

Parker rode his cycle against the defending World Series champion New York “Miracle” Mets at Shea Stadium, and it was one of the brighter moments in a season that quickly found the Dodgers seven games behind CincinnatiâLos Angeles would finish 14

1/2

back. Only 16,552 saw the game, and one thing they don't usually tell you about Parker's cycle is how dramatic it was. Through six innings, the last anyone would have expected was that he was going to achieve the feat.

Parker doubled to lead off a scoreless second inning for the Dodgers, then grounded out to end the fourth. Given a run in the first inning, Mets starter Ray Sadecki was making it hold up, leading 1â0 entering the seventh when Parker led off with a home run to tie the game. A double by Billy Grabarkewitz then chased Sadecki, but the Dodgers ended up tallying three more runs off reliever Tug McGraw.

In the eighth, Parker led off again and singled, but the Dodgers got no other men aboard in the inning. Manny Mota forced Parker, then Mota was caught stealing. By this point, Parker was only one hit away from the cycle, but when you need a triple with a 4â1 lead and one inning to go, and you're due up sixth, frankly, it wasn't even worth mentioning that the last time a Dodger hit for the cycle before Parker, on June 25, 1949, was the Mets manager watching Parker in the opposing dugout, Gil Hodges.

But in the bottom of the eighth, the Mets got three singles and a walk to pull within 4â3 while loading the bases. Joe Foy struck out, and then Duffy Dyer hit a fly ball to right fielder Von Joshua, who mishandled it for an error, allowing the tying run to score. The Dodger victory was in jeopardy, but Parker's attempt at the cycle was very much alive.

Â

Â

Â

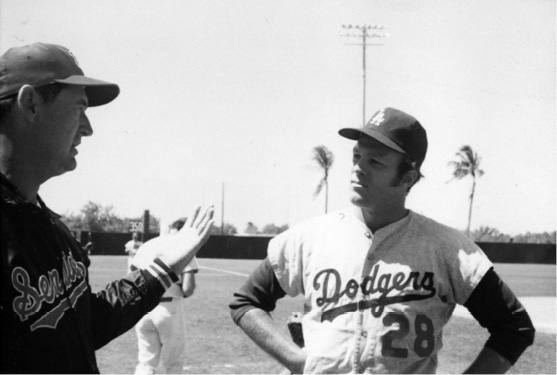

Wes Parker (shown here with Ted Williams) was voted the all-time best fielding first baseman in major league history. Parker also became the first Los Angeles Dodger to hit for the cycle on May 7, 1970. Photo courtesy of www.walteromalley.com. All rights reserved.

Â

The Mets loaded the bases again in the bottom of the ninth with one out, threatening to end the game before Parker could bat, but against Ray Lamb, Ken Boswell grounded into a double play.

When Parker came up for the fifth time in the game, Ted Sizemore was on third base and Willie Davis on first. With everything on the line, Parker nailed it. He hit a triple to center field, a low line drive that zoomed over Tommie Agee's head, bringing home the go-ahead runs and the cycle. Parker later scored, and Lamb made the 7â4 lead stand up, allowing Parker's celebration to go undeterred.

“Really, I'm so thrilled,” Parker said on the radio postgame show after the game, “I really hardly know what to say, because it's been a long uphill climb. You know, for seven years now I've been playing and I've always felt I've been a good hitter, and tonight I finally felt like I arrived finally as a big-league hitter.

“I turned to Harry Wendelstedt, the first-base umpire, in the bottom of the 10

th

inning after there were two outs and said, âHarry, you just saw me have the greatest night I've ever had in baseball.' And he looked at me and just kind of shook his head.”

For years after that, the Dodgers had numerous close calls: more than 300 games in which a batter got three of the four hits he needed for a cycle. By nearly 20 years, it was the longest cycle drought of any major league team (except the two that had never had one: San Diego and Miami). Willie Crawford, Steve Garvey, Gary Sheffield, and Marquis Grissom each had games in which they were missing the easiest hit of all, a single. Garvey, in fact, had three-fourths of a cycle 21 times in his Dodgers career. Marlon Anderson, who already had two singles, a triple, and a homer, could have gotten a cycle if he had stopped at second base when hit the Dodgers' fourth consecutive homer in the ninth inning of 2006's 4â1 game, but that wasn't gonna happen.

The absolute nearest misses after Parker's cycle were by Cesar Izturis on September 8, 2003, and Andre Ethier on September 5, 2008. Needing a double, Izturis lined one to center field and trying to stretch it, slid in safely at second base (according to replays) but was called out. In his game, Ethier needed a triple and laced a ball into the gap in right-center, but hesitated between second and third base and was thrown out. The wait continued.

But finally, Orlando Hudson broke through. Before a sellout crowd in a decorated Dodger Stadium 2009 home opener, the second baseman began his first official game in Los Angeles whites with a modest infield single in the first inning, then drove a homer to left in the third to give the Dodgers a 1â0 lead. One inning later, Hudson's double brought home a run in the Dodgers' six-run fourth inning off Arizona starter Randy Johnson, leaving Hudson half the game to get that elusive triple.

He didn't milk the suspense. Leading off the bottom of the sixth, with “The Ballad of Wes Parker” echoing through the ballpark, Hudson lined one down the line deep to right field and completed the 270-degree circuit with a flourish-filled slide for the first Dodger cycle in nearly 40 years.

For his part, Hudson claimed not to know what he had done, though when he did, he hoped he might get to commemorate the moment. “I was just looking down at the dugout at [Dodger manager Joe] Torre to see if he'd give me a little look, so I could tip my cap,” Hudson told Dylan Hernandez of the

Los Angeles Times

. “I didn't want to make it all about me, you know, but I didn't want the fans to think I was a jerk.”

No risk of that. Hudson had written a ballad all his own.

Â

Â

Triple Triple Plays

The Dodgers had gone 38 years in Los Angeles and 47 years overall without turning a triple play before shortstop Juan Castro ran back and made an over-the-shoulder catch of Chipper Jones' pop fly in Atlanta on June 16, 1996. Braves base runners Marquis Grissom and Mark Lemke had both assumed the ball would drop in for a hit, so Castro was able to turn and fling the ball to Delino DeShields to double up Grissom, and then DeShields threw to Eric Karros at first base to triple up Lemke.

The wait for another triple play wasn't nearly as long, ending almost exactly two years later, on June 13, 1998. Kurt Abbott of Colorado popped up a bunt attemptâenough to freeze teammates Jamey Wright and Neifi Perez on first and second base (the infield fly rule can't be called on bunts). Pitcher Darren Dreifort let the ball drop, and then the throws went from Dreifort to shortstop Jose Vizcaino to force Perez, then to Eric Young at first base to retire Abbott, and finally across the diamond to Bobby Bonilla at third base to tag out Wright. The ol' 1â6â4â5.

The third triple play in Los Angeles Dodger history was also the first 2-5-6-3 triple play in baseball history. On April 15, 2012, runners were on first and second with none out in the top of the ninth of a 4â4 game when Javy Guerra threw a pitch a country mile inside. The ball found a spot on the bat between the hands of Jesus Guzman (who had been attempting to bunt), then landed on the dirt just behind home plate andâas umpire Dale Scott began gesticulatingârolled fair. Dodger catcher A.J. Ellis fired the ball to third base to start the around-the-horn trifecta of outs.

There was an argument that Scott's actions misled the Padres into holding at their bases. However, replays clarified that even if Scott kept his hands at his sides, the Dodgers would have had no trouble recording outs at least at third and first base, if not second as well.

65. Two Infields

In the 1960s and again in the 1970s, the Dodgers unveiled two remarkable infield combinations that people would talk about into the next century. One was a novelty act, while the other was the real deal.

The Dodgers' all-switch-hitting infield is one of the classic Dodgers stories of the '60s, and the way people talk about it, you'd think it was a regular feature at the ballpark. Certainly, it was a renowned foursome: Wes Parker won Gold Gloves year after year, Jim Gilliam was royalty from Brooklyn, Maury Wills a base-stealing legend, and Jim Lefebvre an NL rookie of the year. Yet the four never even played a full season together.

Wills and Gilliam had been Dodgers since the 1950s, while Parker made his debut in '64. Lefebvre graduated to the majors the following year, but newly acquired John Kennedy (coming from Washington with Claude Osteen) made the Opening Day start, not Gilliam, who had retired after the 1964 season to become a coach. But May 28, less than a month after Tommy Davis broke his ankle, Gilliam rejoined the active roster, and in the second game of a doubleheader on May 31, 1965, the four switch-hitters finally made their first ensemble start.

It wasn't a rousing beginning, not with the quartet combining to go 2-for-13 in a 6â1 loss to the Reds. Though the four did make key contributions toward the Dodgers' World Series title, they only made 69 starts that season as a unit. And by '66, the phenomenon was already petering out. Nate Oliver opened the season at third base, leaving the switch-hitting group to start only 25 more games together, scattered throughout the year. Their final bow came in Game 2 of the Dodgers' 1966 World Series drowning, when they went 1-for-13 with two walks in a 6â0 loss to Baltimore.

Gilliam retired from playing for good following the '66 season, Wills went in trade to Montreal, and the Dodgers went into what was at the time a postseason drought.

By 1973, the Dodger infield set aside the switch-hitters but was no more stable, as second and third bases became revolving doors and shortstop only temporarily solidified after Wills came back to the team. But before fans even could realize it, the most steadfast baseball infield of all time was being born. When the Dodgers took the field in the second game of a June 23 doubleheader with Steve Garvey at first, Davey Lopes at second, Bill Russell at short, and Ron Cey at third, it was a grouping that came together almost as if by alchemy.

Russell was the first to establish himselfâbut only after he was converted from the outfieldâby becoming a regular in 1972 and an All-Star game participant in '73. Cey hadn't even had 50 major league plate appearances before 1973 when he nailed down the job, while Lopes was already 27 when he made his major league debut the year before, an age that most players have either hit their prime or their ceiling.

The key change was Garvey. Bill Buckner had been getting the bulk of starts at first base, but Buckner could play left, while it was becoming most apparent that Garvey couldn't play thirdâhe made 28 errors in 85 games in 1972.

“I had always had a strong arm,” Garvey told Steve Delsohn for the latter's oral history of the Dodgers,

True Blue

. “And then my freshman year at Michigan State, I separated my shoulder playing football. It was enough of a separation that I never threw quite the same again after that.

“But it may have been partly psychological, too. Because if I had to make a quick throw, if it was a quick play, boy, it would be on the money. Give me time and who knows where it would be going.”

Barely a year after moving from the trading block to first base, Garvey became the 1974 NL MVP and a perennial All-Star, giving the Dodgers solid and at times exceptional starters at all four infield positions, and for the rest of the decade, management could focus its energies elsewhere. This was no disparate bunch linked only by a rare confluence of ambidextrous ability. This was an

infield

âan infield that helped the Dodgers to three NL pennants in their first five full seasons together (1974â78), a period in which Dodger fortunes looked better than they had at any time since Sandy Koufax's climactic press conference.

After a trashbin of a first half sunk the team in 1979, the team rallied in 1980, only to fall short in the season's 163

rd

game. And then, all of a sudden it seemed, the ninth inning was arriving. By the time the infield returned from the 1981 players' strike, it had passed the eight-year mark together, starting more than 1,000 games side-by-side-by-side-by-side. The game was finally close to ending. Lopes was now 36, and there was new blood in line to replace him in the form of prized prospect Steve Sax. Short of major reversal of fortune, this would be the infield's last shot together.

The good news was that, thanks to MLB's decision to split the season after the strike and award first-half NL West championship to the Dodgers, the team was guaranteed a playoff spot earlier than ever. Starting in July, the focus was October. And though it took a then-record 16 postseason games, they did itâGarvey, Cey, Lopes, and Russell could finally taste World Series champagne.

On February 8, 1982, 14 years after they drafted him, the Dodgers traded Lopes to Oakland for minor leaguer Lance Hudson, who never rose above Class AA ball. Though Lopes would remain productive into his 40s, Sax performed so ably that it helped convince the Dodgers to let Garvey go as a free agent and allow Albuquerque slugger Greg Brock to replace him after the 1982 season. Cey went to the Chicago Cubs in a trade for minor leaguers Vance Lovelace (who years later became a special assistant to the general manager with the Dodgers) and Dan Cataline the following month.

At the end, the last man standing was the first man standing: Bill Russell, the all-time Los Angeles Dodgers leader in games played, a future coach, and a future manager. An era, however, was over.

Â

Â

Â