100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (27 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

77. Willie Davis

“I would say to myself, âThis is the year,' then every time I would go back to my old way of doing things.”

Inside and outside the Dodgers organization, they never seemed to stop psychoanalyzing Willie Davis. No matter what he didâwhether it was hitting 21 homers while stealing 32 bases in 1962, or moving up the franchise leaderboard (he remains first all-time in Los Angeles history in plate appearances, hits, total bases, triples and extra-base hits)âsecond-guessing was ongoing, acceptance grudging. The focus inevitably turned to Davis' internal struggle as a ballplayer, his identity crisis.

“People have been saying for several years that if Willie Davis ever put all his talents together he would be an outstanding ballplayer,” Dan Hafner of the

Los Angeles Times

wrote just before the 1968 season. “The trouble is nobody could ever convince Willie.”

Around the time he first came up as a 20-year-old in 1960, some called Davis the second coming of Willie Mays. Those who saw him run insisted that he was faster than basestealing king Maury Wills. But the combination of Davis' underwhelming offensive numbers following that '62 season and his endless tinkering with his batting stance kept him under scrutiny for the entire decade.

“Willie, you see, did imitations,” wrote Jim Murray. “The only way you could tell it wasn't Stan Musial was when he popped up. But Willie's repertoire included Ted Williams, Billy Williams, Babe Ruth, Babe Herman (usually it came out more like Babe Phelps). He had more shticks than a Catskill comic. He wasn't a ballplayer, he was a chameleon. Sometimes, he imitated three different guys in one night. None of them was Willie Davis. âWillie,' Buzzie Bavasi used to ask him, âWhy don't you arrange it so that somebody imitates you?'”

Even when Davis rolled out a 31-game hitting streak in the late summer of 1969âthe longest streak in baseball since Stan Musial in 1950âbaseball held its breath.

“First he tried to be Stan Musial and then Ernie Banks and he would imitate every hot hitter that came along,” Montreal manager Gene Mauch told Ross Newhan of the

Times

. “Now he's simply Willie Davis and he's damn exciting. If he goes 0-for-10 and changes, he'll be a darn fool.”

Even his teammates, the guys he won two World Series titles with, were left unsatisfied.

“Willie Davis, throughout the 1960s, was regarded as a huge disappointment, a player who never played up to his perceived ability,” historian Bill James wrote. “As John Roseboro said, âHe has never hit .330 in his career. But he should have.'”

But James goes on to make the point that however vexing Davis was, he was judged too harshly, with contemporaries not appreciating the difficult hitting conditions he played in. The midâ1960s in general, and Dodger Stadium in particular, depressed offense considerably.

“Davis was a terrific player,” James said. “True, he didn't walk, and he was not particularly consistentâbut his good years, in context, are quite impressive.... He should not be regarded as a failure, merely because he had to play his prime seasons in such difficult hitting conditions.”

After the 1973 season, Davis still had enough value to be traded to Montreal for reliever Mike Marshall, who would win the NL Cy Young Award for the Dodgers in '74. But Davis played for seven teams (including two in Japan) in his final six seasons, stability having left his baseball life forever.

Â

153

Tommy Davis once held a major league record he has mixed feelings about: most teams in a career. After spending nearly 12 years in the Dodgers organization (including the minor leagues), the Dodgers traded Davis to the Mets in December 1966. Davis ended up playing for eight teams in nine seasons before retiring. (Todd Zeile later shattered his record with 11 teams).

None of that can overshadow the astonishing 1962 campaign that Davis had as a Dodger, in which he collected 230 hits, 120 runs and a franchise-record 153 runs batted in. He had 374 plate appearances with men on base that season and batted .348. RBI are a function of opportunity, but it's safe to say that no Dodger answered opportunity's knock as often as Davis did.

Â

78. The Penguin

Ron Cey played in a couple of giant shadows, one across the diamond in the form of Steve Garvey, the other across the country by the name of Mike Schmidt. With the 5'9", 185-pound, short-striding stature that inspired his “Penguin” nickname, Cey couldn't help being underestimated. He was the comfy chair in the living room, not the

Better Homes & Gardens

centerpiece. But so, so valuable.

Many consider Schmidt, who set third baseman records with 548 home runs, a 147 OPS+ and 10 Gold Gloves in his career, the best in history at the position, so it's understandable that Cey couldn't compete for headlines on that level. But Cey was too accomplished to be as ignored as he was. He ranks 17

th

all-time among third baseman with a 121 OPS+. Cey had underrated range defensively, reaching more balls than the league average year for a third baseman after year while at one point setting a record for consecutive errorless games.

Garvey, of course, was first and foremost in people's minds when it came to the Dodger lineup, wowing Los Angeles with his MVP season in 1974. Yet Cey, while cooling off the more challenging hot corner, was essentially Garvey's equal offensively, edging him for his Dodger career in OPS+ and TAv. Cey just didn't have the glamour. He had thick legs instead of thick arms, he lacked the prime-time haircutâbut most of all, Cey didn't have the cachet that 200 hits a year provided Garvey. Cey had more power and more plate disciplineâwalking more than 1,000 times, but that didn't matter.

Every so often, though, Cey would shine unencumbered. In June 1974, he drove in seven runs in a game, and on July 31, he topped himself with eight. In April 1977, he set a major league record for the month with 29 RBI (on-base percentage of .543, slugging percentage of .890), igniting the Dodgers' 22â4 start. That October, he hit an NLCS Game 1 grand slam and outplayed Schmidt, who went 1-for-16 with two walks in the series.

In the 1981 World Series, nearing the culmination of his Dodger career, Cey's profile took off when he twice hit the dirt. In Game 3, Cey made a diving catch of a sacrifice attempt in foul territory and doubled the runner off first base to protect the Dodgers' 5â4 lead. In the eighth inning of Game 5, Cey was slammed in the head by a screaming Rich Gossage fastball, yet he came back to play in Game 6, drove in the Dodgers' go-ahead run in their title-clinching victory and shared series MVP honors with Steve Yeager and Pedro Guerrero thanks to a 7-for-20, three-walk performance. (Surprisingly left off the official thank-yous was Garvey, despite reaching base in nearly half his at-bats.)

Cey once attributed his major league career to ignorance. “If I'd known the circumstances I'd have to overcome, I probably wouldn't have felt so strongly about it,” he told

Sports Illustrated

writer Larry Keith about his wish to become a ballplayer while a lad in Tacoma, Washington. “I'm not from a good baseball area, and I don't have the size or speed of a lot of players. But baseball is all I ever wanted to do, and I was fortunate to make it, even though a lot of people said I never would.” There might have been reason to underestimate Cey as a kid, but there's no reason to do so now.

Â

Frank Howard

At the time, he was the tallest player in Dodgers history. He was the heaviest player in Dodgers history. But Frank Howard, listed at 6'7”, 255 pounds, was more than just someone you could spot from the moon, more than a candidate for the oddities chapter in the Guinness Book of Dodger Records. As the franchise entered a decade in which they would be starved for runs, Howard was almost the entire power source.

After cups of coffee in 1958 and 1959, Howard became a starting outfielder in May 1960, three months before his 24

th

birthday. By the end of 1964, he would be gone, traded by the Dodgers to the Washington Senators in the deal that yielded pitcher Claude Osteen. In those five seasons, Howard homered 121 times, more than twice as many as any other Dodger during that run-challenged period except Tommy Davis (83). During Dodger Stadium's first two seasons, he hit 52 of the team's 189 homersâ28 percent. And Howard, predictably a below-average fielder, didn't even play every day for the Dodgers (even after winning the 1960 NL Rookie of the Year award), peaking at 141 games in 1962 and averaging 121 per year.

Howard's on-field legacy really remains in the nation's capital, where he ended up hitting 237 of his 382 career homers, including more than 40 per year from 1968 to 1970. From Los Angeles' perspective, Howard's size was usually the biggest part of his story. “Ever since he first showed up, baseball has taken the position Frank's real name was âFrankenstein' Howard, that he had been concocted out of a test tube and a machine that shot blue sparks by a mad scientist in bottle-bottom glasses,” wrote Jim Murray after the trade to the Senators, adding that Howard had become “Washington's second monument.”

79. (Re)read “The Boys of Summer”

The names form such a pantheon of godsâRobinson, Reese, Campanella, Snider, Hodges, Furillo, Erskine, Labineâthat it's too easy to forget that they were human. Not just human in the way some fought racism or a catastrophic injury, but human in the way of immature rivalries, witching-hour confessions, barstool wisecrack perfection, overarching family worries and cherished private memories.

The Boys of Summer

brings that home.

Roger Kahn grew up as a boyhood fan of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and grew up again as a beat writer covering the team for the

New York Herald-Tribune

, and grew up once more when he revisited those select ballplayers a decade after the team had left for Los Angeles. As his initial idolization of those who roamed Ebbets Field in his youth dissolves into a first tenuous, then collegial, then warm bond with them, as he guides us back to and inside that celebrated era of Dodgers history, his wonder and insecurity as traveling companions, Kahn lets his readers simply

be

with the Brooklyn Dodgers of the 1950s.

Â

Â

Â

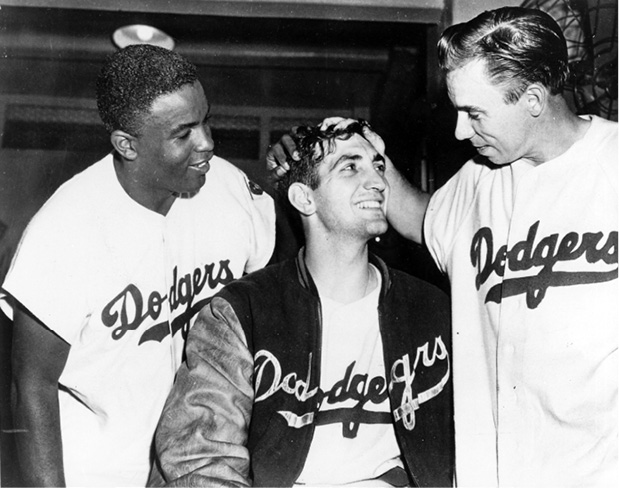

Dodgers greats Jackie Robinson (left) and Pee Wee Reese (right) share a light moment with teammate Ralph Branca. Robinson and Reese, among others, were elevated to god-like status in Roger Kahn's tribute to his beloved Dodgers, The Boys of Summer.

Photo courtesy of www.walteromalley.com. All rights reserved.

Â

If, in the years since its 1972 publication,

The Boys of Summer

has almost drowned in the same kind of unadulterated praise that made the Boys of Summer themselves seem unrealâit's not a perfect book, lagging in certain partsâit is still unique in its clear-headed facility to bring this peak period of Dodgers history to life. For Dodgers fans who have never read it, it's essential. For those who did read it but a generation ago, for those who have been growing up themselves and seen baseball and the world become at once more simple and more complex, it's exactly the type of literature worth revisiting, a treasure trove of experiences meant to be shared and shared again. It's better the second time around.

Â

Dynasty Challenged

In their entire history through 2012, which includes two NL Wild Card appearances, 12 division titles, 21 NL pennants (not to mention the 1889 American Association crown) and six World Series championships, the Dodgers have never played postseason ball more than two seasons in a row. Close calls? Before consecutive playoff appearances in 1995â96, the Dodgers were in first place in the NL West in '94 when the players' union strike shut down the season. But the real chance for even a mini-dynasty was broken in 1954. A five-game deficit to the Giants interrupted what could have been five NL pennants in a rowâsix if it weren't for Bobby Thomson in '51.

Â

80. Bill Russell

Who thought the skinny kid from Pittsburg, Kansas, would wear a Dodgers uniform for more games than anyone else in Los Angeles history? The Dodgers certainly had some amount of faith in Bill Russell, even after he posted batting averages of .226, .259, and .227 playing mostly right field (and experimenting with switch-hitting) as a reserve from 1969â71. During that '71 season, they started moving him to second base, and then on April 27, 1972, with 39-year-old Maury Wills off to a 5-for-47, two-walk, no-steals start, Russell replaced Wills in the seventh inning at shortstop. He went 2-for-2, earning the start the next dayâthe third of his career at that position. Over the next week, Russell went 13-for-23 with three walks, three doubles, and two home runsâyou'd have thought that a Hall of Famer had been born.

Inside of three months, Russell was making enough errors that even he admitted that the team might be relieved to see him depart for two weeks of Army Reserve duty. But overall, the Dodgers liked what they had. For the next 12 seasons, he owned shortstop in Los Angelesâthe first member of the team's record-setting Garvey-Lopes-Russell-Cey infield in, and the last one out.

Russell was Wonder Bread: clean, almost bland, yet a strangely agreeable staple, especially if you weren't accustomed to something more exotic. He tended to blend into the background behind his Dodgers teammates and NL West shortstops like Cincinnati's Davey Concepcion. He wasn't particularly rangy, yet he made at least 28 errors in eight different years. His highest TAv was .270 (in 1982), and some seasons he struggled just to be mediocre at the plate.

But he had his moments. On August 2, 1972, he walked, singled twice, tripled, andâin the bottom of the ninthâhomered to give the Dodgers a 12â11 victory over San Francisco. Three times an NL All-Star, Russell had the game-winning hit in the Dodgers' miraculous ninth-inning comeback at Philadelphia in Game 3 of the 1977 NLCS. The next year, he won the NL pennant for the Dodgers with his 10

th

-inning single to center against the Phillies, then registered a .464 on-base percentage in the World Series.

By the time he retired, after the 1986 season, the soft-spoken shortstop had appeared in a city record 2,181 games, playing for six division winners. And he wasn't done with Los Angeles. For the next five seasons, he became a Dodgers coach, then followed in Tommy Lasorda's footsteps by managing in Albuquerque before returning to the majors as Lasorda's bench coach. When Lasorda suffered his heart attack in July 1996, Russell became only the third manager in Los Angeles history. He guided the Dodgers to a wild-card berth that season, though the team lost its final four games of the regular season and all three in the playoffs. In 1997, the team finished two games out in the NL West.

Russell joined the list of casualties of Fox's purchase of the Dodgers the next year when he was fired at midseason with a 36â38 record. On June 22, 1998âfor the first time since the Dodgers drafted him 42 years beforeâRussell was gone.

Â

Â

Â