(11/20) Farther Afield (17 page)

Read (11/20) Farther Afield Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Pastoral Fiction, #Crete (Greece), #Country Life - England, #General, #Literary, #Country Life, #England, #Fiction, #Villages - England

'A shoe perhaps,' commented some wag, reducing the class to giggles and much explaining of the joke to those who had been too busy chattering themselves to hear.

When order was restored, a more seemly set of reasons was offered for her absence. Someone said she was shopping, John stuck to the foot story with growing vehemence, someone else was equally positive that her mum was bad, while Joseph Coggs' contribution was that she was all right last night because she'd gone scrumping apples with him up Mr Roberts' orchard.

At this innocent disclosure, silence fell. I took advantage of it to point out, yet again, the evils of stealing, and, finally, requested Ernest and Patrick to give out the school books in preparation for a term of solid work.

Temporarily chastened, they settled down to some arithmetic in their rough books, with only minor interruptions such as:

'I've busted the nib off of my pencil.'

'Patrick never give me no book,' and other ungrammatical complaints which I, and thousands of other teachers, deal with automatically, with no disturbance to the main train of thought.

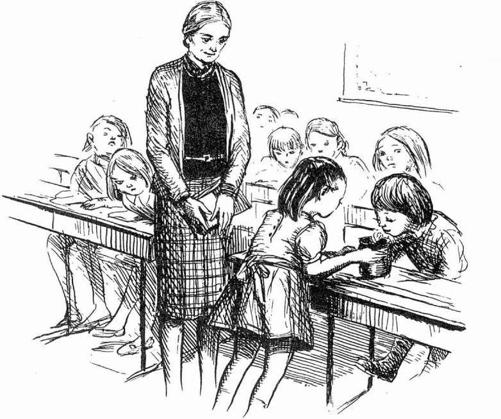

Before half an hour had gone by, however, the infants' teacher appeared at the partition door, holding one of the newcomers by the hand.

The little girl's face was pink with weeping. Tears coursed downward, and it was quite clear that the hanky, thoughtfully pinned by her mother to her frock, had not been used recently.

'Don't worry,' I said. 'Let her stay here with Margaret.' Margaret, motherly in her solicitude, did some much-needed mopping, some kissing and scolding, and took her to sit beside her in the desk. The tears stopped as if by magic.

'Perhaps she would like a sweet,' I said, nodding towards the cupboard where a large tin of boiled sweets is kept for just such emergencies.

Margaret went to get it. There was an expectant hush in the classroom as the children watched the little one select a pear drop. Would I? Wouldn't I?

'You'd better take the tin round,' I said.

One needs something to help the first day along.

The golden day crawled by, and at the end of afternoon school I sauntered through the village to the Post Office to buy National Savings' stamps before Mr Lamb put up his shutters.

This was one of the jobs I should have done during the past week, but somehow the lovely holiday with Amy had unsettled me, and getting back to the usual routine had been extremely difficult.

I found my mind roving back to that delectable island, thinking of the white goats tossing their heads up and down as they nibbled carob branches, of the bearded priests, dignified in their black Greek Orthodox robes, of the smiling peasant we had met up in the hills, carrying a curly white lamb under each arm and the old woman sitting on her doorstep to catch the last of the light, intent upon her handspinning.

That dazzling light, which encompassed all out there, was unforgettable. It served, too, to make me more aware of the subtleties of gentler colour now that I was at home.

As I walked to the Post Office I saw anew how the terra cotta of the old earthenware flower pot in a cottage garden matched the colour of the robin's breast nearby. The faded green paint of Margaret Waters' door was echoed in the soft green of her cabbages. The sweet chestnut tree near the Post Office was thick with fruit, as softly-bristled as young hedgehogs, and matching the lime-green tobacco flowers which are Mr Lamb's great pride.

Mrs Coggs was busy fining in a form, assisted by the postmaster. She wrote painfully and slowly, far too engrossed in the job to notice me, and I waited while Mr Lamb did his instructing.

'Now just your name, Mrs Coggs. Here, on this line.'

The pen squeaked, and I thought how patient he was, bending so kindly over his pupil. He moved, and a shaft of sunlight fell across Mrs Coggs' arms. I was disturbed to see that they were badly bruised, and so was the hand that held the pen so shakily.

'And here?' she asked, looking up.

'No, no need for you to fill that in. I can do that for you. That's all now, Mrs Coggs. I'll see to it.'

She gave a sigh of relief, and turned. I saw that one eye was black.

'Lovely day, miss. Had a nice holiday?'

'Yes, thank you. Are you all well?'

'Baby's teething, but the rest of us is doin' nicely.'

She nodded and smiled, and went out to the baby who was gnawing its fists in the pram.

'Doing nicely,' echoed Mr Lamb, when she had pushed the pram out of earshot. He put Mrs Coggs' form tidily, with others, in a folder.

'Beats me why she stays with that brute,' he went on. 'Did you see her arms? And that black eye?'

I nodded.

'I bet she copped that lot last Saturday. Arthur had had a skinful down at "The Beetle and Wedge", I heard. That chap drinks three parts of his wage packet – when he earns any, that is – and she's hard put to it to get the rent out of him.'

'I thought things seemed better now they were in a council house.'

Mr Lamb snorted, and began to open the folder holding savings' stamps without even asking my needs.

'Better? You'll never alter Arthur Coggs even if you was to put him in Buckingham Palace! Usual, I suppose?' he said, looking up.

'Yes, please.'

'Pity she never left him before all those children came. Now she's shackled, and he knows it. Gets her in the family way every two years or so, and there she is tied with another baby and another mouth to feed, poor devil.'

'I wonder how we can help,' I said, thinking aloud. 'It might be an idea to have a word with the district nurse.'

'If you're thinking she can help with the pill and that,' said Mr Lamb, 'you'll have to think again. If Arthur got wind of anything like that, he'd knock the living daylights out of the poor woman.

He folded the stamps and I put them in my bag. To my surprise, he looked rather embarrassed as he scrabbled in the drawer for my change.

'Shouldn't be talking of such things to a single lady like you, I suppose.'

I said that I had been conversant with the facts of life for some time now.

'Yes, well, no doubt. But you can take it from me,' miss, you've a lot to be thankful for, being single. "When I see poor souls like Mrs Coggs coming in here, I wonder women get married at all.'

'Mrs Lamb seems happy enough,' I observed. 'Not all husbands are like Arthur Coggs, you know.'

'That's true,' conceded Mr Lamb. 'But nevertheless, you count your blessings!'

I pondered on Mr Lamb's advice as I walked back to the school house through the sunshine. It reminded me again of Amy's plight, of Mrs Clark's at the hotel, and of all the complications which, it seemed, married life could bring. Somehow, in the last few months, the advantages and disadvantages of the single and the married states had been thrust before me with disconcerting sharpness.

After tea, still musing, I took a walk through the little copse at the foot of the downs. Honeysuckle was in flower in the hedges, and the wood itself was heavy with the rich smells of summer. Yes, I supposed that I should count my blessings, as Mr Lamb had said. I was free to come and go as I pleased. Free to wander in a summer wood, when scores of other villagers were standing over stoves cooking their husbands' meals, or were struggling with children unwilling to go to bed whilst the sun still shone.

And yet, and yet.... Was I missing something as vital as Amy insisted? I remembered the sad monk at Toplou, the garrulous schoolteacher, the victim of loneliness, on the flight home, and a dozen more single people who perhaps were slightly odd when one came to think about them. But any odder than the married ones?

I began to climb the path up the downs beside a wire fence. A poor dead rook had been hung there, as a warning, I supposed, to others. I looked at the glossy corpse with pity as it hung upside down, its beautiful wings askew, like some wind-crippled umbrella. How quickly life passed, and how easily it was extinguished!

I looked up at the downs and decided I should turn back. Moods of melancholy are rare with me, and this one had quite worn me out. What, I wondered, besides the encounter with Mrs Coggs, had brought it on? Could I, at my advanced age, be love-lorn, regretting my lost youth, pining for a state I had never known? A bit late in the day for that sort of thinking, I told myself briskly, and not the true cause of my wistfulness anyway.

It appeared much more likely to be caused by the first day of term combined with an unusually nasty school dinner.

I returned home at a rattling pace, ate two poached eggs on toast, and was myself again.

16 Gerard and Vanessa

O

NE

afternoon, a week later, I stood at my window and watched large hailstones bouncing on the lawn like mothballs. With any luck, the children should have got home before this sudden summer storm had broken, and any loiterers had only themselves to blame.

I was carrying out my tea tray to the kitchen when the telephone rang. It was Amy.

'Are you free this evening?'

'Yes. Anything I can do?'

'Yes, please. Come over to dinner. Gerard and Vanessa are here, just arrived. He's on his way to town, and has a lunch appointment tomorrow. I've persuaded him to stay the night. Do say you'll come.'

I said I should love to and would be with them at seven-thirty, if that suited her.

'Knowing you,' said Amy, 'you will be on the doorstep at seven-ten, asking what's on the menu. I warn you, mighty little! It's the company you're coming for!'

She rang off, and I was left to wonder how many times Amy has upbraided me for punctuality. Personally, I cannot bear to wait about for visitors who have been asked for seven or seven-thirty, and who elect to come at eight-fifteen while the potatoes turn from brown to black, and I stand enduring a fit of the fantods.

It was good to be going out, and I put on a silk frock which Amy had not yet seen, and hoped it would please her eye. I had seen nothing of her since our return, although we had spoken briefly on the telephone once or twice. How things were going with naughty James, I had no idea.

The hailstorm was over by the time I set out – carefully not too early – but it was cold and blustery. I took the back way to Bent, enjoying the distant view of the downs with the grey clouds scudding along their tops.

Vanessa opened the door to me. She was looking very pretty in a long blue frock, and her favourite piece of jewellery without which I have never seen her. It consists of a hefty brown stone, quite unremarkable, threaded on a long silver chain which reaches to her waist. I have nicer looking pebbles in the gravel of my garden path, but obviously Vanessa sets great store by this ornament, and one can only suppose that she has sentimental reasons for wearing it.

'Lovely to see you again,' she said, kissing my cheek, much to my surprise. 'Come and see Gerard. He brought me down, as I've some leave due to me, and Aunt Amy said I could come here for a few days.'

Gerard was as pink and cheerful as ever.

'Doesn't he look well?' commented Amy, 'I'm so glad he's staying the night. He's meeting his publisher tomorrow. It sounds important, doesn't it?'

'It is to me,' said Gerard. 'They're suggesting that I attempt another book. We're meeting to see how the land lies.'

'But what about the Scottish poets?' I asked.

'Ticking over nicely. I should get them done within a month or so.'

We talked of this and that over our drinks, and I had to give him the latest news of Fairacre, with particular reference to Mr Willet and our local poet, Aloysius Stone, now long-dead, but not forgotten, in the parish.

Over dinner Amy told him about Crete with many interruptions from me. The black silk scarf had been received by Vanessa with expressions of joy and, what's more, with an offer to pay for it which had taken Amy completely off-guard.

'Of course, I couldn't possibly allow it,' she said to me privately afterwards. 'But I was very much touched by the offer. I must say Eileen's brought her up very well.'

As always, Amy's scratch meal turned out to be far more sophisticated and enjoyable than one had been led to expect.

After avocado pears stuffed with shrimps, we had a beef casserole and then fruit salad. I sat enjoying the fruit and thinking idly how typical it was of Amy to be able to produce avocado pears, not to mention everything else, at an hour or so's notice.

'This sliced banana,' said Vanessa dreamily, 'lying on my plate, is wizened to the likeness of a cat's anus.'

'

Really

!' exclaimed Amy, putting down her spoon with a clatter.

'Oh, it's only a quotation,' explained Vanessa, becoming conscious of our startled gaze upon her. 'One of our waiters is a poet, and he wrote it.'

'Well, I don't think he should be quoted at table, if that's typical of his work,' said Amy severely.

'He's really terribly gifted. He's had a book of poems published. I meant to tell you, Gerard dear. You may be able to help him. He paid three hundred pounds, he told me, to have them printed.'

'More fool him,' said Gerard.

'But couldn't you put in a word for him tomorrow when you meet your publisher?'