1492: The Year Our World Began (35 page)

Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

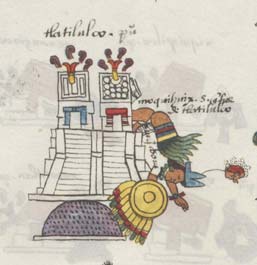

Codex Mendoza

’s depiction of the legendary culture hero, Tenuch, guided by an eagle to found Tenochtitlan in its defiantly mountainous lakebound island.

J. Cooper Clark, ed.,

Codex Mendoza,

3 vols. (London, 1938), iii. Original in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

In North America, most native origin myths depict the people as having sprung from the land, with a right of occupancy that dates from the beginning of time. The Aztecs saw themselves differently. They were self-proclaimed migrants who came from elsewhere and whose rights were rights of conquest. They told two rival stories about their past. In one, they were Chichimeca, dog people, former nomads and savages who ascended to the valley of Mexico from the deserts to the north and who survived as victims of longer-established denizens, through sufferings that demanded vengeance. In the second version of the myth, they were descendants of former hegemons, the Toltecs, whose homeland lay to the south, where the ruins of their great city of Tula had lain abandoned for centuries. Strictly speaking, the two stories are mutually contradictory, but they convey a consistent message: of warlike provenance, lost birthright, and imperial destiny.

Tenochtitlan could not even have survived, let alone launched an empire, without an ideology of violence. Its site is over seven thousand feet above sea level, at an altitude where some of the key crops that nourished Mesoamerican ways of life will not grow. There is no cotton, of which, by the late fifteenth century, Tenochtitlan consumed hundreds of thousands of bales every year for everyday clothing and for the manufacture of the quilted cotton armor that trapped the enemy’s blades

and arrowheads. Cacao, which Mesoamericans ground into the theobromine-rich infusion that intoxicated the elite at parties and in rituals, is a lowland crop that grows only in hot climates. The Tenochca speckled their lake with “floating gardens” laboriously dredged from the lake bed, for producing squashes, corn, and beans. But even these everyday staples were impossible to grow in sufficient amounts for the burgeoning lake-bound community. Only plunder on a grand scale could solve the logistical problems of keeping the city fed and clothed.

As the reach of Aztec hegemony lengthened, demand for exotic luxuries increased. Hundreds of thousands of bearers arrived laden with exotic tribute from the hot plains and forests, coasts, and distant highlands: quetzal feathers and jaguar pelts; rare conches from the gulf; jade and amber; rubber for the ball game that, like European jousting, was an essential aristocratic rite; copal for incense; gold and copper; cacao; deerskins; and what the Spaniards called “smoking-tubes with which the natives perfume their mouths.” Elite life, and the rituals on which the city depended to stay in favor with the gods, would have collapsed without regular renewals of these supplies. The flow of tribute was both the strength and the weakness of Tenochtitlan: strength, because it showed the vast reach of the city’s power; weakness, because if the tribute flow stopped, as it would do soon after the Spaniards arrived and helped rouse the subject peoples against the empire, the city would shrivel and starve.

In and around 1492, no such prospect loomed: it was probably unthinkable. Ahuitzotl became Aztec paramount in 1486. In 1487, at the dedication of a new temple in his courtly center at Tenochtitlan, the captives sacrificed were reliably estimated at more than twenty thousand. By the time of his death in 1502, tribute records credited him with the conquest of forty-five communities—two hundred thousand square kilometers. In the reign of his successor, Montezuma II, who was still ruling in Tenochtitlan when the conquistadores arrived, forty-four communities are listed, but the momentum never relaxed. Montezuma’s armies shuttled back and forth from the Pánuco River in the

north, on the gulf coast, across the isthmus and as far south as Xonocozco, on what is now the frontier of Mexico and Guatemala. The Spaniards did not find a spent empire, or a state corroded by diffidence or undermined morale. On the contrary, it is hard to imagine a more dynamic, aggressive, or confident band of conquerors than the Aztecs.

For the Aztecs’ victims, the experience of conquest was probably more of a short, sharp shock than an enduring trauma. The fact that many communities appear repeatedly as conquests in the rolls the Aztecs preserved, as records of who owed them tribute, suggests that many so-called conquests were punitive raids on recalcitrant tributaries. The glyph for conquest is an image of a burning temple, suggesting that defeat was a source of disgrace for local gods. One of the astonishing features of Mesoamerican culture before the conquest is that people revered the same pantheon throughout and beyond the culture area the Aztecs dominated. So maybe the worship of common deities spread with war. But nothing else changed in the culture of the vanquished.

Typically, existing elites remained in power, if they paid tribute. Wherever records survive in the Aztec world, ruling dynasties at the time the Spaniards took over traced their genealogies back to their own heroes and divine founders, in unbroken sequences of many hundreds of years. It was rare for Tenochtitlan to intrude officials or install garrisons. In early colonial times the Spaniards, who were looking hard for indigenous precedents for their own style of government in an attempt to represent themselves as continuators, rather than destroyers, of indigenous tradition, could find only twenty-two cases of communities ruled directly from Tenochtitlan, and most of those were recent conquests or frontier garrison towns, suggesting that direct rule, where it occurred, was a transitional, temporary device.

So the hegemony of Tenochtitlan was not an empire in the modern sense of the word. For years, when I was teaching Mesoamerican history to undergraduates, I sought a neutral word to describe the space the Aztecs dominated. I felt immensely pleased with myself when I thought of calling it by the vague German term

Grossraum,

which literally means

“big space.” But my pleasure fled when I realized, first, that the undergraduates could not understand what I meant and, second, that it was an absurd evasion to pluck a term from a culture that had nothing to do with the case. We may as well call it what it was: a tribute system of unparalleled complexity.

The complexity is obvious from the lists of goods that fill documents from the preconquest archives of the Tenochca state. For Tenochtitlan, no tributary was more important than the city’s nearest neighbor, Tlatelolco, which was on an adjoining island in a shared lake. Its strategic proximity was dangerous, and its loyalty was essential. Indeed, Tlatelolco was the only ally that never deserted Tenochtitlan but fought on, during the siege of 1521, until the end, while the Spaniards detached all the other formerly allied and subject communities, one by one, from Tenochtitlan’s side, by intimidation or negotiation. In keeping with the city’s supreme importance, Tlatelolco got special treatment from the illustrators of

Codex Mendoza.

Instead of using a simple name glyph to signify the city, they devoted much space to a lively depiction of the city’s famous twin towers—the double pyramid, reputedly the highest in the Aztec world, that adorned the central plaza. They also showed the conquered chief of Tlatelolco, whom the Tenochca called Miquihuixtl, hurling himself drunkenly down the temple steps in despair. More remarkable than the way they depicted the city is the tribute they listed—including large quantities of cotton and cacao, which could no more grow in Tlatelolco than they could elsewhere in the region. So Tlatelolco was evidently receiving tribute from farther afield and passing it on to Tenochtitlan.

Other cities privileged in the imperial pecking order levied and exchanged tribute in similar ways. Tenochtitlan topped the system, but it was not entirely exempt from the exchange. Annually, in mock battles, the city engaged in a ritualized exchange of warriors for sacrifice with Tlaxcala, a community on the far side of the mountain range to the southeast of Tenochtitlan. The terms of exchange favored the hegemonic city, and Tlaxcala was also listed as paying tribute in other

forms, including deerskins, pipes for tobacco, and cane frames for loading goods on porters’ backs. But the system marked Tlaxcala out as special. When the Spaniards arrived, the Tlaxcalteca tested them, welcomed them, allied with them, used them against their own regional enemies, and supplied more men and material for the siege of Tenochtitlan than any other group.

The fall (1473) to Tenochca conquerors of the neighboring city of Tlatelolco with the spectacular death of the defeated ruler, Moquihuixtl.

J. Cooper Clark, ed.,

Codex Mendoza,

3 vols. (London, 1938), iii. Original in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Power in the Aztec world was many-centered, elusive, and exercised through intermediaries. Traditionally, historians represented the Inca hegemony as a complete contrast: highly centralized, systematic, and uniform. Inca imperialism was indeed different from that of the Aztecs, but not in the ways commonly supposed. Peter Shaffer’s play of 1964,

The Royal Hunt of the Sun,

the best-ever dramatization of the conquest of Peru, captures received wisdom in a brilliant passage of dialogue. Under

the supreme Inca’s all-seeing gaze, symbolizing the reach of his intelligence service, the Spaniards interrogate natives about the nature of the empire and hear that its organization is comprehensive, inflexible, and irresistible. The population is divided not among disparate natural communities but into bureaucratically contrived units of a hundred thousand families. The state controls all food and clothing. Every month, the people unite in the apportioned tasks of the season: plowing, sewing, roof mending. Obligations to the state dominate every phase of life. The ruler interrupts the dialogue to explain: “Nine to twelve years, protect harvests. Twelve to eighteen, care for herds. Eighteen to twenty-five, warriors for me—Atahuallpa Inca!”

The image is appealing, but misleading. The Inca system was not centralized. It did not resemble the “state socialism” that Shaffer’s Cold War–era play portrays. On the contrary, the empire had distinctive relationships, crafted to meet each individual case, with almost every one of its subject communities.

The vision of Inca power crushing diversity out of the empire was a construction of early colonial historians. Some of them were clerics or conquistadores. They exaggerated Inca power to flatter the Spaniards who overthrew it and the saints who supposedly helped. Other makers of the myth were the descendants of the Inca themselves, who aggrandized their ancestors by making them seem equal or superior to European empire builders. Garcilaso de la Vega, for example, the most accomplished writer on the subject in the sixteenth century, whose book on his ancestors appeared eighty years after the Spaniards arrived in Peru, was the son of an Inca princess. He lived as what Spaniards called a

señorito,

embodying gentlemanly affectations, in the Andalusian town of Montilla, which was small enough and remote enough for him to be the most important local personage. His status is measurable in his scores of godchildren. For him the Incas were the Romans of America, whose perfectly articulated empire exhibited all the qualities of order, organization, military prowess, and engineering genius his European contemporaries admired in their own accounts of ancient Rome.

Roman models, however, are almost useless for understanding what the Incas were like. The best route is via the ruins of the states and civilizations that occupied the Andes before them. From the seventh century to the tenth, the metropolis of Huari, nine thousand feet up in the Ayacucho Valley, preceded and in some ways prefigured the Inca empire. The town had barracks, dormitories, and communal kitchens at its center for a warrior elite, while a working population of some twenty thousand gathered around it. Satellite towns around the valley imitated it, probably because they were colonies or subject communities. To judge from similar evidence farther afield, the influence or power of Huari reached hundreds of miles over mountains and deserts to Nazca. The Huari zone overlapped with the Incas’ home valley of Cuzco, and the memory of their achievements remained potent.

Deeper inland, higher into the mountains, in an area that became a target for Inca imperialism, lay the ruins of the city of Tiahuanaco, near Lake Titicaca, with an impressive array of raised temples, sunken courtyards, triumphal gateways, fearsome reliefs, crushing monoliths, and daunting fortifications. Spread over forty acres at an altitude higher than that of Lhasa in Tibet, it was a real-life Cloud Cuckoo Land, twelve thousand feet above sea level. Potatoes fed it. No other staple would grow so close to the snow line. To cultivate the tubers, the people built platforms of cobbles, bedding the potatoes into topsoil of clay and silt. To supply irrigation, and for protection from violent changes of temperature, they dug surrounding channels from Lake Titicaca. The potato fields stretched nine miles from the lakeside and could yield thirty thousand tons a year. The state warehoused huge amounts and converted crops into

chuñu,

a gastronomically unappealing but vital substance made by freeze-drying potatoes in the conducive climate of the high Andes. Tiahuanaco was obviously an imperial enterprise. To supplement potatoes, and to ensure against blight, the inhabitants had to conquer fields at lower altitudes, where they could grow quinoa and what modern Americans call corn—that is, maize.