1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (21 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

Plasmodium

’s contribution to the birth of the United States was stronger still. In May of 1778 Henry Clinton became commander in chief of the British forces during the Revolutionary War. Partly on the basis of inaccurate reports from American exiles in London, the British command believed that the Carolinas and Georgia were full of loyalists who feared to announce their support of the home country. Clinton decided upon a “southern strategy.” He would send a force south, which would hold the region long enough to persuade the silent loyalist majority to declare its support for the king. In addition, he promised, slaves who fought for his side would be freed. Although Clinton didn’t know it, he was leading an invasion of the malaria zone.

Although almost forgotten today, yellow fever was a terror from the U.S. South to Argentina until the 1930s, when a safe vaccine was developed. This cartoon illustrated a magazine article about an 1873 outbreak in Florida. (

Photo credit 3.6

)

English troops were not seasoned; indeed, two-thirds of the troops who served in 1778 were from malaria-free Scotland. To be sure, many British soldiers had by 1780 spent a year or two in the colonies—but mostly in New York and New England, north of the

Plasmodium

line. By contrast, the southern colonists were seasoned; almost all were immune to vivax and many had survived falciparum.

British troops successfully besieged Charleston in 1780. Clinton left a month later and instructed his troops to chase the Americans into the hinterlands. The man he put in charge of the foray was Major General Charles Cornwallis. Cornwallis marched inland in June, high season for

Anopheles quadrimaculatus

. By autumn, the general complained, disease had “nearly ruined” his army. So many men were sick that the British could barely fight. Loyalist troops from the colonies were the only men able to march. Cornwallis himself lay feverish while his Loyalists lost the Battle of Kings Mountain. “There was a big imbalance. Cornwallis’s army simply melted away,” McNeill told me.

Beaten back by disease, Cornwallis abandoned the Carolinas and marched to Chesapeake Bay, where he planned to join another British force. He arrived in June 1781. Clinton ordered him to take a position on the coast, where the army could be transported to New York if needed. Cornwallis protested: Chesapeake Bay was famously disease ridden. It didn’t matter; he had to be on the coast if he was to be useful. The army went to Yorktown, fifteen miles from Jamestown, a location Cornwallis bitterly described as “some acres of an unhealthy swamp.” His camp was between two marshes, near some rice fields.

To Clinton’s horror and surprise, a French fleet appeared off Chesapeake Bay, sealing in Cornwallis. Meanwhile, Washington marched south from New York. The revolution was so short of cash and supplies that his army had twice mutinied. Nonetheless an opportunity had arisen. The British army was unable to move; Cornwallis later estimated that only 3,800 of his 7,700 men were fit to fight. McNeill takes pains to credit the bravery and skill of the revolution’s leaders. But what he wryly referred to as “revolutionary mosquitoes” played an equally critical role. “

Anopheles quadrimaculatus

stands tall among the Founding Fathers,” he said to me. With Cornwallis’s troops falling to the Columbian Exchange in ever-greater numbers, the British army surrendered, effectively creating the United States, on October 17, 1781.

Click

here

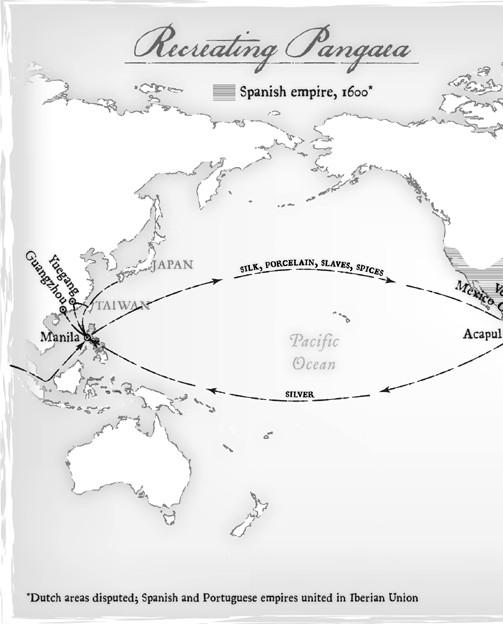

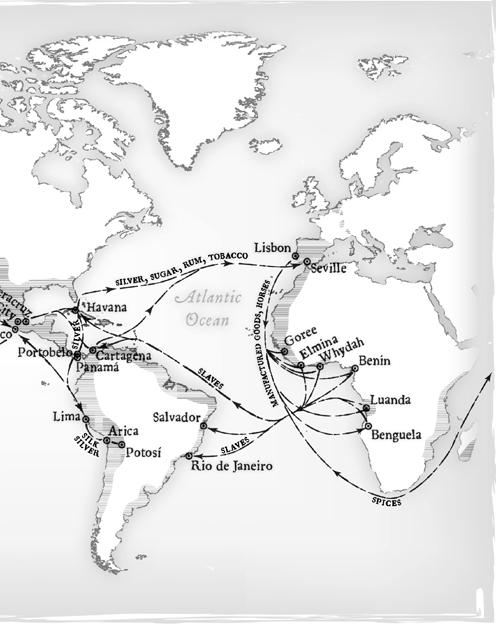

to view a larger image of this entire map.

Click

here

to view a larger image of this entire map.

1

It may seem odd that malaria, a tropical disease, flourished in England of the Little Ice Age. But history is an interplay of social and biological processes. Just as Elizabethan marsh-draining techniques unintentionally helped vivax flourish, the improved drainage methods of the Victorian era dramatically cut malaria, because they didn’t leave the brackish pools, thus simultaneously eliminating mosquito habitat and creating better pasturage for cattle, which

A. maculipennis

, if given the choice, prefers to feed upon. Even so, researchers routinely found “thousands” of the insects roosting “in the dark and ill-ventilated pigsties” of poor coastal farmers as late as the 1920s. Today some fear that global warming will foster the spread of malaria. But if people continue destroying mosquito habitat by draining wetlands the hotter weather may have no impact on malaria rates.

2

Early arrival of the parasite could help explain, too, why Opechancanough never expelled the colonists, even after almost wiping them out in 1622. Debilitated by disease, the Powhatan might have had difficulty mounting a sustained war. Unhappily, these intriguing speculations have the disadvantage of having no empirical support.

3

These figures do not include Indians seized in other colonies. During a vicious Indian war in 1675–76, for instance, Massachusetts sent hundreds of native captives to Spain, Portugal, Hispaniola, Bermuda, and Virginia. And the French in New Orleans seized thousands more. Carolina was a bigger slaver than others, but every English colony in North America was in the same business, with or without the cooperation of local Indians.

PART TWO

Pacific Journeys

4

4 Shiploads of Money

Shiploads of Money

(Silk for Silver, Part One)

“THAT EXTRA LITTLE EFFORT”

Vastness was its greatest characteristic, with wonder close behind. The vastness—intimidating, confounding, beyond credence—spoke clearly from a hundred miles away. It is said that kings in their palaces looked over the ocean to see a new mountain range on the horizon: wide-bellied ships by the hundred, rigged fore and aft, soldiers massed at their bulwarks. Strange warlike banners snapped from the topgallants. The armada was larger than any before or since. It must have seemed

geographic.

Wonder attended its sails, followed by capitulation and obeisance. These were the great maritime expeditions sponsored by the Ming emperor Yongle in the early fifteenth century. Such a mark did they leave that some historians believe they were the font of the stories of Sinbad the Sailor.

Built in enormous dry docks, encrusted with precious metals, replete with technical innovations—double hulls, watertight compartments, rust-proofed nails, mechanical bilge pumps—that Europe would not discover for a century, the Chinese ships were marvels for their time. The flagship of their commander, Zheng He, was more than 300 feet long and 150 feet wide, the biggest wooden vessel ever constructed. Records claim it had nine masts. Zheng’s grandest expedition had 317 ships, an amazing figure even now. The Spanish Armada, then the largest fleet in European history, consisted of just 137; the biggest was half the size of Zheng’s flagship.

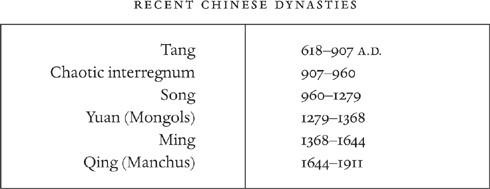

Zheng himself was among the more unlikely figures to grace Chinese history. Strikingly tall and powerfully built, a Muslim from the backlands, he was captured as a child in 1381 during one of the Yuan dynasty’s last battles against the invading Ming. (For a synopsis of Chinese dynastic history, see the chart on

this page

.) Standard treatment by the Ming of enemy boys was castration. The emasculated Zheng was pressed into service at the Ming court and gained a reputation for shrewdness and competence. Displaying his eye for the main chance, he jumped to support a coup in which the monarch’s uncle seized power from his nephew. The usurper became the Yongle emperor.

1

Zheng became one of his most trusted lieutenants. When the ambitious sovereign planned a series of sea expeditions, he put his favorite eunuch in charge.

To celebrate the 2010 Olympics, China displayed this exact copy of Zheng He’s flagship. Six centuries after the original was built, the ship still was large enough to dazzle crowds. (

Photo credit 4.1

)

The voyages began in 1405 and ended in 1433 and took Zheng across the Indian Ocean as far as southern Africa. The Yongle emperor viewed them as a way to throw his weight around, and they were powerfully effective. During these voyages Zheng’s fleet subjugated a misbehaving Chinese enclave in Sumatra; intervened in a civil war in Java; invaded Sri Lanka and took its captured ruler to China; and wiped out bandits in Sumatra. Even where no swords were unsheathed Zheng’s armadas were a political triumph, scaring the wits out of every foreign leader who saw them. But the voyages were not followed up. They had become a target in political infighting—one bureaucratic faction championing them, another trying to take down the first by decrying their expense. Yongle’s son and successor aligned with the faction that opposed his father’s policies. He canceled the grand naval adventures on the day he ascended to the throne. Ultimately almost all records of Zheng’s travels were suppressed. China didn’t again send ships so far outside its borders until the nineteenth century.

Many researchers have seen the failure to continue as emblematic of a fatal insularity in Chinese society. “Why did China not make that extra little effort that would have taken it around the southern end of Africa and up into the Atlantic?” asked Landes, the Harvard historian, in his

Wealth and Poverty of Nations.

Landes’s answer: “The Chinese lacked range, focus, and above all, curiosity.” Hobbled by Confucian ideology, arrogant and complacent, China was “a reluctant improver and a bad learner.”

The European Miracle,

University of Melbourne historian Eric Jones’s celebrated account of the West’s climb to political dominance, similarly attributes China’s rejection of foreign adventures to “empty cultural superiority” and “self-engrossment.” After Zheng He, the empire “retreated from the sea and became inward-looking.” China, the McGill University political scientist John A. Hall charged in

Powers and Liberties: The Causes and Consequences of the Rise of the West,

“was stuck in the same stage for over two thousand years, while Europe, in comparison, progressed like a champion hurdler.” Bubbling with entrepreneurial vim, Portugal, the Netherlands, Spain, and Britain dragged sclerotic China into the rough-and-tumble of the outside world.

Other scholars disagree with this image of Chinese passivity. Nor do they believe the shutdown of Zheng He’s voyages exemplified a cultural lack of curiosity or drive. No matter how far the admiral traveled from home, these writers note, he never encountered a nation richer than his own. Technologically speaking, China was so far ahead of the rest of Eurasia that foreign lands had little to offer except raw materials, which could be obtained without going to the bother of dispatching gigantic flotillas on lengthy journeys. Beijing easily could have sent Zheng past Africa to Europe, observed the George Mason University political scientist Jack Goldstone. But the empire stopped long-range exploration “for the same reason the United States stopped sending men to the moon—there was nothing there to justify the costs of such voyages.”

In a broader sense, though, the question remains. Zheng’s voyages were an exception to a longer, more consequential trend. During most of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Beijing issued edicts that effectively banned private sea trade. The Yongle emperor and a few other rulers opened it up, but they were exceptions; as a rule, the dynasty clamped down on international exploration and exchange. So draconian were the prohibitions that in 1525 the court ordered coastal officials to destroy all private seagoing vessels.

As puzzling in today’s context as the shutdown was its reversal. Fifty years after the demolition order another emperor reversed course. With the court bureaucracy’s reluctant blessing, a new generation of Chinese ships went on the waters. Soon the Ming had been drawn into a worldwide network of exchange. In a trice, the Chinese economy became enmeshed with Europe (a place previously regarded as too poor to be worth bothering with) and the Americas (a place the emperors hadn’t known existed).

The court had long feared that unrestricted trade would lead to chaos. Indeed, it did have catastrophic by-effects, though not those predicted by imperial bureaucrats. I’ve already described how the Columbian Exchange across the Atlantic shaped economic and political institutions. Now I turn to the Pacific, where the economic exchange established itself first and greased the skids for the Columbian Exchange. Accordingly, this chapter concerns economics and politics. The next chapter describes their ecological consequences; an environmental convulsion that had dire economic and political consequences for China—among them, in part, its later collapse before the West.

“MERCHANTS WERE PIRATES, PIRATES WERE MERCHANTS”

Why did China let in the flood? The decision was driven by two factors, one largely political, one largely economic. The political factor was the Ming desire to enhance the power of the state. Beijing’s prohibition on private trade had less to do with an abhorrence of trade than a desire to control it for the dynasty’s benefit. Unhappily, the attempt backfired—the reaction to the trade ban ended up weakening government control, rather than strengthening it. When Beijing finally admitted this, it abandoned its previous policy. Further driving the emperors to make this decision was the economic factor: China had severe money woes. Literally so—the empire had lost control of its own coinage, and merchants had to buy and sell goods with little lumps of silver. To obtain the necessary silver, China lifted its trade ban, opening itself to the world. Soon the great ships of the galleon trade were carrying silk and silver across the Pacific—the final links in the global economic and ecological network begun by Colón’s efforts in the Caribbean islands and Legazpi’s sojourn in the Philippine islands.

Chinese history is divided into dynasties, beginning before 2000 B.C. The tally here is simplified; the Song dynasty, for instance, is usually split into two eras (it fell apart after an invasion and regrouped with its power center in a different place). And this list doesn’t show the messy transitions between dynasties—the Ming dynasty is usually said to have seized power in 1368, but fighting with the Yuan lasted for several decades before and after that date.

The Ming trade bans have often been described as emblems of Chinese cultural deficiency (Landes: “the Confucian state abhorred mercantile success”). But they were more complicated than that. The bans did not stop

all

foreign contact. They permitted one exception: “tribute payments,” in which foreigners, hosted in designated government hostels, were generously allowed to offer presents to the throne. Then the emperor would, out of politeness, give them Chinese goods in return. He also allowed them to sell anything he didn’t want, which was often quite a lot.

Coastal merchants recognized the ban-and-tribute scheme for what it was: a way for the government to control international commerce. It was a busy, lucrative affair—in 1403–04, at the height of the supposed ban on foreign merchants, the Ming court hosted “tribute delegations” from no less than thirty-eight nations. Naturally, the Ming wanted the profits from trade. What the dynasty didn’t want was the traders themselves; foreign goods, not foreign people. With a few exceptions, all contact with the world outside was supposed to be supervised by Beijing.

2

With bureaucratic logic, court bureaucrats reasoned that because maritime trade was outlawed the nation therefore didn’t need a coastal force to police that trade. China reduced its navy to a few vessels, not enough to patrol the nation’s long coastline. The entirely unsurprising result was a delirium of smuggling (if business is outlawed, only outlaws will do business).