1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (62 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

Sick, miserable, insect-bitten, dressed in tatters, Stedman’s force futilely chased runaway slaves through the forest for three years. They fought exactly one battle. They won that battle, as the adage goes, but lost the war. “Out of a number of near twelve hundred Able bodied men, now not one hundred did return to theyr Friends at home,” Stedman wrote sadly, “Amongst whom Perhaps not 20 were to be found in perfect health.” All the others, he said, were “sick; discharged, past all Remedy; Lost; kill’d; & murdered by the Climate, while no less than 10 or 12 were drown’d & Snapt away by the Alligators.”

Eventually the Dutch and the maroons reached a kind of accommodation. The Europeans kept shipping in Africans and growing cane, accepting that a certain number of slaves would escape each year. Meanwhile, most of the Dutch colonists stayed as little as they could; in 1850, after two centuries of colonization, Suriname had perhaps eight thousand European residents, most of them agents for sugar planters who lived safely in the Netherlands. Not residing in the colony, the growers had little interest in creating the institutions that underlie a productive society. Every scrap of profit went back to the home country; education, innovation, and investment in Suriname were almost entirely ignored. When Suriname became independent in 1975, it was one of the poorest countries in the world.

Naturally, the new nation sought development. Suriname has large deposits of bauxite, gold, diamond, and oil and more tropical forest per capita than any other nation. The cash-strapped government—both the military dictatorship that seized power in 1980 and its civilian successor, which began in 1992—awarded mining and timber rights to foreign companies. In the 1960s, the colonial government had let Alcoa, the big aluminum company, build a six-hundred-square-mile lake to feed a hydroelectric dam for aluminum refining. Now the independent government awarded China International Marine Containers, the world’s biggest container-manufacturing firm, the rights to log almost eight hundred square miles to make wooden shipping pallets. Other firms followed suit. By 2007 some 40 percent of the country’s surface area had been leased for logging.

All the while the government was fending off environmentalists’ criticism by creating parks. At a joint press conference in 1998 with Conservation International, the nation announced that it had set aside six thousand square miles—10 percent of its territory—to create the Central Suriname Nature Reserve, the world’s biggest protected tropical forest. “Suriname’s example,”

The New York Times

editorialized, is “a small ray of hope.” UNESCO named the park a World Heritage Site in 2000, lauding it as “one of the very few undisturbed forest areas in the Amazonian region with no inhabitants and no human use.”

Beginning with the blood-drinking treaty of 1762, the Dutch had recognized the autonomy of six maroon groups, of which the biggest today are the Saramaka and Ndyuka, with about fifty thousand people each. None had been apprised beforehand about the logging and mining concessions, though many were on their land. None had been consulted about the dam, which inundated maroon villages (in a further insult, the turbines silted up and are now useless). Nor had they been asked about the park, which includes part of the homeland of the Kwinti, the smallest of the six maroon groups, who have been in that area since about 1750. (It also houses an Indian group called the Trio.) The government’s actions led a coalition of Saramaka leaders to file a complaint with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in October 2000. Angered, Suriname’s president charged that the Saramaka petition showed that they wanted to ally with Columbian narco-guerrillas to foment civil war. The government vowed to continue opening land to logging and mining, a stance it reiterated when the commission ordered that the process be suspended, and reiterated again in November 2007, when the Inter-American Court of Human Rights demanded that Suriname give the Saramaka control over their resources.

The nation has not complied, as of the time of this writing. Indeed, the jousting among maroons, governments, and large corporations seems likely to last for years. The stakes are nothing less than the future of the tropical forest itself, and the maroons are not fighting only in Suriname.

SHAKE IT, OX!

In 1991 Maria do Rosario Costa Cabral and her siblings bought twenty-five acres on the banks of Igarapé Espinel (Espinel Creek), a sub-sub-tributary of the Amazon in Amapá, Brazil’s northeasternmost province. A wiry, watchful woman of sixty-two, Dona Rosario was born into a maroon community called Ipanema—a place so poor, she told me, that families cut their matches in half lengthwise to make a box last twice as long. Her father spent his days as a rubber tapper, toting the latex to one of the small natural-rubber distributors that still hang on in the area. If he and his friends showed up with a lot of rubber, wealthier people would realize they had found an especially productive group of trees. They would figure out the location, force out the rubber tappers, and take over. The same thing happened with their farms. They would acquire abandoned land—a plantation that had failed twenty or thirty years before—and pull out a few harvests. Just as the family was settling in, men with guns would show up. You are squatters, they would say. If they had a contract, they would say the title was invalid. Leave now, they would say, touching their weapons. Little changed when Dona Rosario reached adulthood. Repeatedly she set up farms and repeatedly she was pushed off them. Still, she jumped at the opportunity to buy the land on Igarapé Espinel.

To non-Amazonians, the property wouldn’t have seemed worth troubling about. It is located about two hundred miles from the river’s mouth, where the Amazon is so large that it acts like a tidal body—tides flood the area twice a day. The force is so large that deep within the forest nameless streams well over their banks and march inland, sometimes for miles. People build their homes on stilts and paddle their canoes between the trees. Even when the surface is exposed, it is thick with gooey mud. I visited Dona Rosario’s farm recently with Susanna Hecht, the UCLA geographer. The mud soon covered us to our knees and practically ripped the boots from our feet.

Dona Rosario told us that she got the property cheap, because it had been ravaged by the heart of palm craze of the late 1980s, when every fashionable menu from London to Los Angeles had to feature heart of palm salad. Heart of palm is the growing tip and inner core of young palm trees, particularly South American species like açai (

Euterpe oleracea

), jucura (

Euterpe edulis

), and pupunha (peach palm,

Bactris gasipae

). Determined to wring every penny out of the forest that they could, palm hunters scoured the lower Amazon with the implacability of paid assassins. Barges discharged crews with axes and winches who chopped down entire palm groves to obtain the edible tips (the hearts can be removed without killing the tree, but this takes more time). If they spotted anything else that looked valuable, they took that, too. “The land was looted,” Dona Rosario told us. “It was a mass of vines and scrub.”

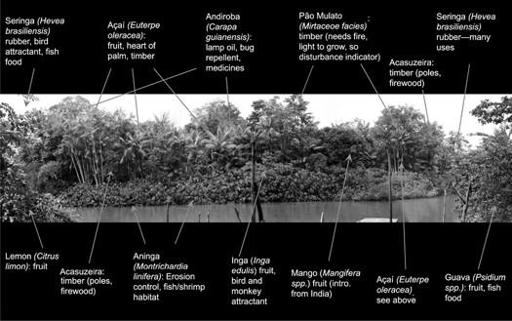

She set out to bring it back with techniques she had learned from her father in the region of her birth. With help from her sisters and brothers, she planted fast-growing timber trees for sawmills upriver. For the market, they put in fruit trees: limes, coconut, cupuaçu (a relative of cacao prized for its fragrant pulp, rather than its seeds), and açaí (formerly used for heart of palm, the tree has purple fruit that produce a yogurt-like pulp). With woven shrimp traps—identical to those in West Africa, Hecht told me—the family caught shrimp and kept them alive in cages that drifted in the creek. At the river’s edge they encouraged shrubs that made habitat for fish and fry and planted trees with seeds and fruit that would attract them into the flooded forest. To an outside visitor, the result looked like a wild tropical landscape. The difference was that almost every species in it had been selected and tended by Dona Rosario and her family.

Dona Rosario lives on the fringes of a sprawling

quilombo

complex centered on Mazagão Velho (Old Mazagão), founded in 1770 by transplanting almost entire the last Portuguese colony in North Africa. The year before, the inhabitants had fled before a Muslim army, arriving as a body in Lisbon. Treating defeat as opportunity, the Portuguese court ordered the community to resettle en masse in Amapá, where its presence was supposed to thwart potential incursions by French Guiana, Amapá’s northern neighbor. A Genoese engineer designed the new town as a graceful Enlightenment-era city, complete with public squares and gridded streets. Slaves actually built more than two hundred houses in what was then called Vila Nova Mazagão (Mazagão New Town); the Portuguese may have moved as many as 1,900 people into them. The transition was eased by grants of cash, livestock, and several hundred slaves. Soon the newcomers made the unhappy discovery that the lower Amazon, unlike the dry, breezy Moroccan coast, is hot and humid—it is located almost exactly on the equator. Within a decade of arrival the colonists—malarial, famished, living in wretched huts they were too poor to repair—were begging the crown to relocate them. Ultimately, almost all of the surviving Europeans slipped away. The remainder soon died. Through no act of their own, the slaves found themselves at liberty. Vila Nova Mazagão had become a

quilombo.

Hundreds of

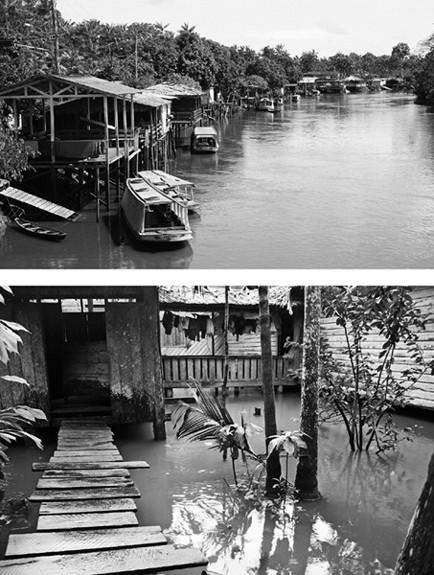

quilombos

were established in the lower Amazon, a maze of rivers that tidally spill over their banks twice a day, washing a mile or more into the interior. Because the rivers are the main transport routes, villages spread out along the banks (top, Anauerapucu, in the state of Macapá); houses are built on stilts (bottom, in Mazagão Velho) to let the tidewater pass beneath the floorboards. (

Photo credit 9.5

)

They were free as long as they pretended they weren’t. The Portuguese administration wanted to be able to report to the king that his subjects were guarding Brazil’s northern flank. The slaves were willing to say they were doing it, if that meant they would be left alone. Everyone was happy: the maroons pretended they were Portuguese subjects in a Portuguese colony and the Portuguese pretended the maroons were guarding the frontier. As the decades went by, the descendants of the colony’s Africans spread out along the riverbanks, living much like their Indian neighbors. The river supplied fish and shrimp, the small-scale garden cultivation yielded manioc, the trees provided everything else. Two centuries of constant tending and harvesting structured the forest. Mixing together native and African techniques, maroons created landscapes lush enough to be mistaken for pristine wilderness.

So did others. Portuguese euphoria from the destruction of Palmares had been short-lived. Slaves continued to escape and to live in the forest. But they didn’t repeat the mistake of forming big, centralized communities like Palmares. Instead they created ten thousand or more small villages in a flexible, shifting network that spread across much of eastern Brazil and the lower Amazon. They mixed with extant native settlements, collected Indian slave escapees, threw open their doors to Portuguese misfits and criminals. Many Africans had lived in tropical environments before being shipped across the ocean. They were comfortable in hot, wet places where people farmed palms and kept trapfuls of shrimp in the stream. They were happy to learn when Indians showed them how to fish by scattering poison in a tributary or make protective “boots” by melting latex over their feet or squeeze the bitter compounds out of manioc with long, tubular baskets. Ideologically opposed to “going native,” the Portuguese were much less willing to adjust. In consequence, the forest seemed dangerous to them, a place to be ventured into only with an army. Ceding the field to

quilombos,

the colonists were only partially aware that the escaped slaves were living within a short walk of the plantations, as in Calabar or Liberdade. In consequence, the

quilombos

were left largely alone—unless they were unlucky enough to be in the path of gold miners, rubber tappers, or other people who sought quick wealth in the forest.