1808: The Flight of the Emperor (10 page)

Read 1808: The Flight of the Emperor Online

Authors: Laurentino Gomes

São Paulo, today the largest metropolis in South America, then was a small town of 20,000 inhabitants, including slaves.

25

At the junction of various commercial routes between the coast and the interior and between the south and the rest of the country, it can also be considered the most indigenous and most Brazilian of all of the great colonial cities, according to journalist Roberto Pompeu de Toledo, author of

The Capital of Solitude,

an excellent book about the history of the

paulista

capital. Tupi, a native language, was the most widely spoken language in São Paulo, even by Europeans, until the eighteenth century, when Portuguese became the dominant language. The majority of the population slept in hammocks, a tradition inherited from the natives, until the middle of the nineteenth century, when beds finally replaced them. Homes were little more than adaptations of

ocas,

traditional indigenous dwellings. During the first two centuries of the colony, “the diet of the Indians was followed, weapons of the Indian were used, and

Nheengatu,

the

lingua-geral,

or indigenous-based lingua franca, was spoken as much as or even more than Portuguese,” recounts Pompeu de Toledo.

26

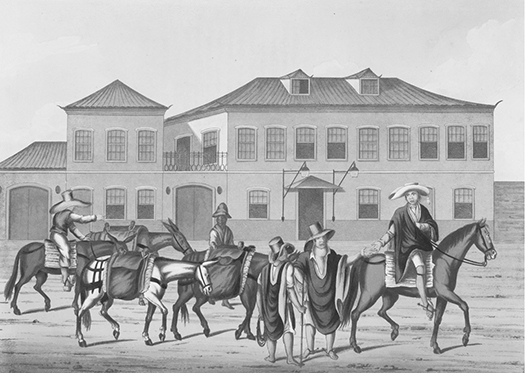

The drawings of Austrian artist Thomas Ender, who reached Brazil in 1817 with Princess Leopoldina (recently married by proxy in Vienna to the future emperor Pedro I), show

paulista

men and women wearing dark cotton

jackets and trousers and gray felt hats with wide brims tied with cords below the chin. They secured their loose boots of raw leather, dyed black, below the knee with straps and buckles. Men kept long knives with silver handles in their belts or upright in their boots, to use as weapons or as cutlery during meals. During trips to the interior by horse or by caravan of mules, they protected themselves against the cold using long, wide, blue ponchos. This apparel was so common in São Paulo that for many years it was called

paulista

, until falling into disuse with the disappearance of the troopers, and became typical of the

gaúchos

of Rio Grande do Sul.

27

One peculiarity caught the attention of almost all visitors from abroad passing through São Paulo at the time: the large number of prostitutes in the streets at night on the heels of troopers. They used wide wool mantles to cover their shoulders and part of their faces. Governors of the captaincy at various times had prohibited these cloaks, called

baetas

, in vain attempts to contain prostitution. In 1775, Martim Lopes Lobo instituted fines and threats of jail for whoever used them. In August 1810, Captain General Franca e Horta ruled that slaves caught with baetas must not only pay a fine but be beaten with a paddle. The fines went toward the lepers' hospital, but none of these measures had any lasting effect. Thomas Ender and his botanical colleague Karl von Martius described the very same scenes in the streets of São Paulo a decade later.

28

The economic heart of the colony beat in the triangle formed by São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais. The axis of development moved to this region in the beginning of the eighteenth century after the end of the sugarcane boom in the Northeast and the discovery of gold and diamonds in Minas.

29

In his travel notebooks, the botanist von Martius, who also arrived in Princess Leopoldina's retinue, described the incessant movement of mule troopers between São Paulo and Minas Gerais in 1817:

Â

Each troop consists of 20-50 mules, conducted by a muleteer on horseback, in charge of the general direction of the convoy. It is he who gives the orders to depart, rest, spend the night, rebalance the cargo, assesses the state of the yokes and the conditions of the animals, whether they are injured or unshod. Under his orders the carters travel by foot, each

one of them in charge of seven mules, who they have to load and unload with cargo, lead to pasture, and cook for themselves and the other travelers. The muleteer, generally a freed mulatto, also takes care of buying and selling goods in the city, representing the commission of the owner of the troop. The carters are mostly black, and who seek such work as they find the wandering and adventurous life preferable to laboring in the mines or on the farms.

30

Muleteers supplied a colony awash in ignorance and isolation.

Troperos or Muleteers,

engraving from

Views and Costumes of the City and Neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro

by Henry Chamberlain, London, 1822, Lucia M. Loeb/Biblioteca Guita e José Mindlin

On the troops' route lay waystations and outposts that served as shelter and restocking points for the men and their animals. “It is a custom of these travelers not to carry food,” noted von Martius. “As in every place they find shops providing rations and ingredients ready to be prepared.” These meals generally consisted of beans cooked with lard, accompanied by dried meat

and a dessert of cheese and banana. At night they slept under a mantle made of ox hide, extended over a grating supported by small pieces of wood stuck into the soil.

31

A sugarcane mill.

A Sugar Mill,

engraving from

Travels in Brazil

by Henry Koster, London, 1816, Lucia M. Loeb/Biblioteca Guita e José Mindlin

Arriving in Rio de Janeiro in 1808, the Englishman John Luccock immediately identified the problem of a lack of currency. Simply put, no money circulated in Brazil. Under the Portuguese dominion, the colony essentially subsisted on bartering, which greatly restricted the opportunities that new merchants could exploit in a country recently opened to international trade. “The commerce between Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais consists principally in negroes, iron, salt, woollens, hats, printed cottons, hard-ware, arms, and some fancy articles, a little wine and oil, salt-fish, and butter,” related John Mawe. “Few luxuries enter these remote parts, the inhabitants seeking for little beyond mere necessities.”

32

Mawe also speaks of the dietary habits in Minas Gerais:

Â

The master, his steward, and the overseers, sit down to a breakfast of kidney beans of a black colour, boiled, which they mix with the flour of Indian corn, and eat with a little dry pork fried or boiled. The dinner generally consists, also, of a bit of pork or bacon boiled, the water from which is poured upon a dish of the flour above-mentioned, thus forming a stiff pudding. A large quantity (about half a peck) of this food is poured in a heap on the table, and a great dish of boiled beans set upon it: each person helps himself in the readiest way, there being only one knife, which is very often dispensed with. A plate or two of colewort or cabbage-leaves complete the repast. The food is commonly served up in the earthen vessels used for cooking it; sometimes on pewter dishes. The general beverage is water. At supper nothing is seen but large quantities of boiled greens, with a little bit of poor bacon to flavour them. On any festive occasion, or when strangers appear, the dinner or supper is improved by the addition of a stewed fowl.

33

As a result of the gold and diamonds springing forth from the ground, the population of Minas exploded in the eighteenth century. At the height of its prosperity, Vila Rica was the largest city in Brazil with 100,000 inhabitants. Tijuco, modern-day Diamantina, had 40,000 people in the era of Chica da Silva, the famous slave who became rich after she won the heart of a rich Portuguese diamond mine owner.

34

But when the royal court docked in Brazil, the cycle of gold already had reached its end. The German geologist Wilhelm von Eschwege calculates that, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, 555 gold and diamond mines still existed in the colony, directly employing 6,662 laborers, of which only 169 were free men; the remaining 6,493 being slaves of course.

35

Prospecting and mining activity devastated vast swaths of land. “On all sides, we had before our eyes the afflicting vestiges of panning, vast regions of earth stirred up, and mountains of pebbles,” wrote botanist Augustin de Saint-Hilaire while traveling through the interior of Minas Gerais. “As far as the eye can see, there is earth overturned by human hands, from so many dreams of profit spurring the will to work.”

36

The control over mining was rigorous. By the laws of the Portuguese government, gold extracted from mines and alluvia had to be delivered to the

foundry houses in each district, where the rights of the crown were charged. One fifth of the mineral dust was reserved for the king. Another 18 percent went to the coining houses.

37

The rest stayed with the prospectors and miners in the form of bars marked with weight, carat, number, and the king's coat of arms, along with a certificate allowing them to enter into circulation. To facilitate commerce, the circulation of gold dust was also authorized in small quantities and used for day-to-day purchases. Aside from the severe control of foundry houses, surveillance posts dotted the roads, especially between the mines and the coast, where a military garrison composed of a lieutenant and fifty soldiers had the right to inspect anyone passing through. The punishment for smuggling was drastic: imprisonment, confiscation of all goods, and deportation to Africa.

Still, smuggling dominated the majority of commercial activity in the colony despite all attempts to prevent it. Precious stones and metals flowed along the Rio da Prata in the direction of Buenos Aires. From there, they proceeded to Europe without paying tax to the Portuguese crown. Historian Francisco de Varnhagen calculates that 40 percent of the total gold was diverted illegally.

38

Mawe describes the imprisonment of a smuggler in the village of Conceição, in the interior of Minas:

Â

About a week previous to my arrival, this village was the scene of a somewhat remarkable adventure. A tropeiro going to Rio de Janeiro with some loaded mules was overtaken by two cavalry soldiers who ordered him to surrender his fowling-piece; which being done, they bored the butt-end with a gimblet, and finding it hollow, took off the iron from the end, where they found a cavity containing about three hundred carats of diamonds, which they immediately seized.

The trooper went to prison in Tijuco and the diamonds were confiscated. “The fate of this man,” judged Mawe, “is a dreadful instance of the rigour of the existing laws: he will forfeit all his property, and be confined, probably, for the remainder of his days in a loathsome prison, among felons and murderers.”

39

Despite an isolationist policy and the stiff control of the Portuguese government, the colony was still more dynamic and creative than the decaying

and stagnant metropolis in Portugal, not only in economic terms but also in the arts and sciences. Between 1772 and 1800, a total of 527 Brazilians graduated from the University of Coimbra, at the time the most respected university in the Portuguese empire and a center for the formation of an intellectual elite that constituted what Sérgio Buarque de Holanda called “the Brazilian ruling class.” A quarter of the graduates came from the captaincy of Rio de Janeiro, 64 percent of them trained in law, which offered the most professional opportunities at the time, especially in the public sector.

40

One of the Brazilians trained in Coimbra was José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva, the future Father of Independence. A mineralogist of international renown, de Andrada e Silva also wrote the first treatise for the Royal Academy of Sciences in Lisbon on the improvement of whaling techniques.

41

He had traveled through all of Europe, observed the French Revolution in Paris, and participated in the offensive in Portugal against Napoleon's troops, organized by the British after the court's flight.

42

He was probably more experienced and prepared than any other Portuguese statesman or intellectual of his time.