1808: The Flight of the Emperor (13 page)

Read 1808: The Flight of the Emperor Online

Authors: Laurentino Gomes

The painter Jean-Baptiste Debret, who arrived at the French Artistic Mission in Brazil in 1816, also found shocking the lack of good table manners among the rich:

Â

The man of the house eats with his elbows jutting on the table; the lady with the plate on her knees, seated on her settee, in oriental fashion; the children, lying or squatting on mats, gladly smearing themselves with the food in their hands. If they are wealthier, the merchant might add a loin of grilled or boiled fish with a spring of parsley, a quarter of an onion, and three or four tomatoes. But to make it more appetizing, they would dip every mouthful in spicy sauce. Bananas and oranges would complete the meal. Only water was drunk. Women and children used neither fork nor knifeâthey all ate with their hands.

18

Fresh meat was a rarity. It came from afar, sometimes six hundred miles away. Many of the oxen driven along substandard roads from Minas Gerais or the ParaÃba Valley died along the way from hunger or exhaustion. “Those of which held out to the end arrived in a most miserable condition, at a public Slaughter-house,” recounts Luccock. Situated near the center of Rio, the slaughterhouse was “highly distressing, and always of the filthiest description.” The condition of the animals, including how they had been slaughtered and transported, turned the meat so bad that “nothing but dire necessity, or the perpetual sight of it in the same wretched condition, could induce a person of the least delicacy to taste it.” Pork also was sold “in a very diseased state.” For these reasons, dried meat from far awayâsalted and cured in the sunâwas more widely consumed.

19

Despite the rarity of freshly slaughtered meat, the population of Rio de Janeiro had a rich and varied diet. It consisted of many fruits, such as bananas, oranges, passion fruits, pineapples, and guava, as well as fish, fowl, vegetables, and legumes. Bread baked from wheat flour proved rare and very expensive. Flour made from cassava root or corn flour was used throughout the colony. Together with dried meat and beans it completed the basic pyramid of the Brazilian diet.

In 1808, Rio de Janeiro had only seventy-five public spaces or areas of usage, composed of forty-six roads, four alleyways, six backstreets, and nineteen fields or plazas.

20

The names of the roads help explain their purpose: Praia do Sapateiro: Shoemaker's Beach, today Flamengo Beach; Rua dos Ferradores: Blacksmiths' Street, today Alfandega; Rua dos Pescadores: Fishermen's Street, today Visconde de Inhaúma; and Rua dos Latoeiros: Tinsmiths' Street, today Gonçalves Dias. The main street was Rua Direita, today 1st of May Avenue, featuring the house of the governor, the customs house, and later the Carmo Convent, the mint, and the Royal Palace itself.

During the week, the bustling, noisy streets of the city teemed with mules and four-oxen carriages carrying construction materials, the friction of their wheels and axles making a noise like iron-cutting. Historian Jurandir Malerba recounts that the largely forgotten language of church bells measured and announced the rhythms of life. Nine clangings announced the birth of a boy, seven the birth of a girl. The incessant roar of cannons on the numerous ships and forts protecting the city shocked visitors. “In homage to the King, every ship entering the port would fire off 21 shots, responded in turn by the forts on shoreâa custom unknown to any other part of the world,” writes Malerba.

21

In 1808, 855 ships entered the port of Rio de Janeiro, an average of three per day.

22

If each fired 21 shots, followed by a response of equal number from the forts, then each day by nightfall each carioca heard no fewer than 126 rounds of cannon fire.

In fact, depending on the ship, this number could reach much higher. In 1818, Henry Brackenridge, a naval official from America, entered Guanabara aboard the frigate

Congress

on an official mission. The protocol of salute involved an exchange of no fewer than seventy-two cannon shots. First, the American frigate discharged twenty-one shots saluting the king, immediately

echoed by twenty-one more from one of the forts guarding the bay, followed by fifteen more shots in salute of the admiral, who responded in equal proportion. Only thereafter could the

Congress

dock in port. “The Portuguese appear to be extremely fond of expending their powder,” remarked a surprised Brackenridge. “Hardly an hour of the day passed without the sound of cannon in some direction or other.”

23

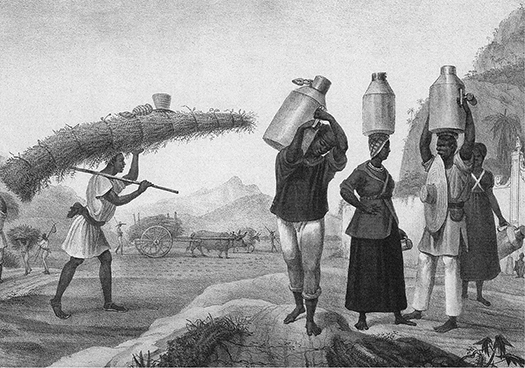

Slaves and freed black merchants selling coal, corn, hay, and milk.

Another aspect of the city that piqued visitors' curiosity was the number of blacks, mulattos, and mestizos in the streets. Slaves undertook every type of manual labor. Among other activities, they were barbers, shoemakers, couriers, basket makers, and merchants selling hay, refreshments, sweets, cornmeal, and coffee. They also carried around people and goods.

24

In the morning, hundreds of them fetched water from the fountain in the Carioca aqueduct, transporting it in barrels similar to those used to carry sewage to the beach in the afternoons.

25

Negros vendedores de carvão e vendedorias de milho and Vendedores de leite e capim,

engravings by Jean-Baptiste Debret from

Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil,

Paris, 1834â1839, as in

Rio de Janeiro, cidade mestiça,

Companhia das Letras, 2001

“The racket is incessant,” complained Ernst Ebel, a German visitor describing the noise of slaves in the streets transporting merchandise.

Â

A mob of half-naked slaves carrying sacks of coffee on their heads, led forward by one who sings and dances to the rhythm of a cowbell or beating two shackles in the lilt of a droning stanza which the rest of them repeat, two more carrying on their shoulders a heavy barrel of wine, suspended on a long pole, intoning a melancholy ditty at every step; further ahead, a second group carrying bales of salt, wearing nothing more than a loincloth, indifferent to their burden and to the heat, race around shouting at the top of their lungs. Chained to one another, six more appear yonder with buckets of water on their heads. They are criminals employed as public servants.

26

Slaves dominated the landscape on holidays and weekends as well. Wearing colorful clothes, ornaments, and turbans, they gathered in the Santana Fields, in the suburbs of the city, where they sang and danced, clapping in large circles. “On every Saturday and holiday, which are called festival days, masses of negroes travel there, reaching a total of ten or fifteen thousand,” described two visitors. “It is quite curious recreation, and offers a unique spectacle of happiness, tumult, and confusion, which is probably not possible to see on the same scale anywhere besides Africa itself.”

27

In addition to discomfort, the combination of heat and lack of hygiene generated massive health problems. “The people are very subject to fevers, to bilious complaints, and what are called diseases of the liver, to dysentery, and elephantiasis, and to other disorders of a similar, and probably connected, kind, which are often violent and fatal,” observed John Luccock. “The small pox, too, when it makes its appearance, carries off multitudes; but lately its ravages have been checked by vaccination.”

28

In 1798, the Chamber of Rio de Janeiro proposed to a group of doctors a program to combat epidemics and eradicate the endemic maladies of the city. The plan included a survey of these illnesses. The report, completed by Army doctor Bernardino Antonio Gomes, is frightening:

Â

According to an observation of nearly two years in Rio de Janeiro, I have counted that the endemic maladies of the city include scabies, erysipelas, mycoses, yaws, morphea, elephantiasis, pruritus, tungiasis, leg oedema, hydrocoeles, sarcoceles, roundworms, hernias, leuchorrea, dysmenorrhea, haemorrhoids, dyspepsia, various convulsions, hepatitis, and different types of intermittent and recurring fever.

29

Aided by the medical report, the aldermen raised the suspicion that the primary source of these epidemic illnessesâespecially scabies, erysipelas, pox, and tuberculosisâlay with the recently arrived blacks from Africa. The councilmen suggested transferring the slave market from the Plaza 15th of November to some location further away. Seeing their business interests threatened, slave traffickers sued the Municipal Chamber. A legal

dispute dragged on, ending only when the viceroy, the marquis of Lavradio, sided with the aldermen and ordered the transfer of the slave market to the Valongo region, where it remained when Prince João arrived in Brazil.

30

But even more difficult than diagnosing the cause of various diseases was fighting them. As was the case everywhere in the colony, no university-trained doctors lived in Rio de Janeiro. Hearkening back to the Middle Ages, barbers practiced a rudimentary form of medicine. Thomas O'Neill, a lieutenant of the British Navy who accompanied the prince regent, noted with intrigue the number of barbers and the purposes that they fulfilled: “The barbers shops are singular, as they are designated by the sign of a basin; and the barber unites in himself the three professions of a surgeon, dentist, and shaver.”

31

Carioca researcher Nireu Cavalcanti found documents in the Brazilian National Archives that give a sense of the state of health and medical care in Rio in the time of King João VI. The post-mortem inventories of doctors, they record possessions left behind. One of them, of the head surgeon Antonio José Pinto, who died in 1709, includes the following startling list of “surgical instruments”: a large hand-saw, a small hand-saw, a ratchet, two straight knives, two pairs of pliers, an eagle's claw, two tourniquets, a spanner wrench, and a large pair of scissors. An inventory of Antonio Pereira Ferreira, a pharmacist who died in the same year, gives an idea of the assortment of drugs available at the time. The list includes compresses, fungus, minerals, oils, peels, roots, seeds, and a curious item listed as “animals and their parts” with “human oil,” “lizard sandpaper,” “raw salamander eyes,” “deer antler shavings,” and “wild boar teeth.”

32

The arrival of the royal family in Rio de Janeiro soon effected a revolution in architecture, the arts, culture, customs, health, and sanitation, everything changing for the betterâat least for the white elite who frequented the court. Between 1808 and 1822 the city tripled in size with the creation of new neighborhoods and parishes.

33

The population grew 30 percent, while the number of slaves tripled from 12,000 to 36,182.

34

Animal and coach traffic grew so intense that laws and regulations had to restrain it. Rua Direita became, starting in 1824, the first road in the city with numbered addresses and traffic organized in a two-way street with separate lanes.

Despite the rapid growth, in 1817, nine years after the royal family's arrival, Austrian naturalist Thomas Ender registered the presence of a group of natives in São Lourenço, one of the entrances to Guanabara Bay, not far from the Palace of São Cristovão, where King João VI lived. It was doubtless the last indigenous stronghold close to the capital of a Brazil still desolate and unexplored.

XIII

Dom João

J

oão, prince regent and, after 1816, king of Portugal and Brazil, had a crippling fear of crustaceans and thunder. During the frequent tropical storms in Rio de Janeiro, he took refuge in his rooms in the company of his favorite valet, Matias Antonio Lobato. With a candle lit, the two prayed to Santa Barbara and San Jeronimo until the thunder ceased.

1

On another occasion, a tick bit him while he visited the ranch at Santa Cruz where he spent his summers. The wound became inflamed, and he developed a fever. Doctors recommended a bath in the ocean. Terrified of being attacked by crustaceans, he ordered the construction of a wooden box in which he bathed in the waters of Caju Beach near the Palace of São Cristovão. Essentially a portable bathtub, the box had two crosswise poles and holes in the sides through which seawater entered. The king remained inside for a few minutes, the box submerged and held tight by slaves, as the marine salt helped the wound form a scab.

2

These improvised washings on Caju Beach, under medical advice, remain the only evidence of any baths that the prince took during his thirteen years in Brazil. Almost all historians describe him as unkempt and averse to bathing. “He was very dirty, a bad habit he shared with the rest of the family and the rest of the nation,” affirms Oliveira Martins. “Neither he, nor D. Carlota, despite hating each other, differed on the rule of not bathing.”

3

The

reluctance of the Portuguese court to bathe contrasted sharply with the Brazilian colony, where attention to personal cleanliness caught the attention of nearly every visitor. “Despite certain habits that come close to savagery among the Brazilians of lower classes, it must be remarked that whatever their race, every one of them is notably attentive to bodily cleanliness,” wrote Henry Koster, who lived in Recife from 1809 to 1820.

4

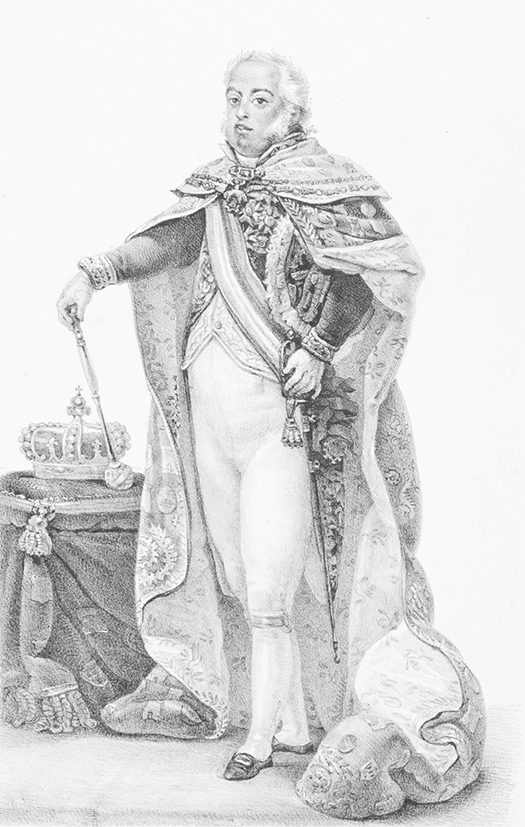

Despite his defects of personality, King João VI, here with royal scepter, crown, and mantle, knew how to delegate power and weather geopolitical turbulence.

O rei D. João VI,

engraving by Jean-Baptiste Debret from

Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil,

Paris, 1834â1839, Lucia M. Loeb/Biblioteca Guita e José Mindlin

João Maria José Francisco Xavier de Paula Luis Antonio Domingos Rafael de Bragança was the last absolute monarch of Portugal and both first and last ruler of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves, which existed barely longer than five years. Born on May 13, 1767, he died on March 10, 1826, two months before his fifty-ninth birthday. Paintings of him reveal, in the words of historian Ãngelo Pereira:

Â

A high forehead, disproportional to his face, sharply defined eyebrows, sagging cheeks and jowls, rather buggy eyes, a fine nose, thick lips, a half-opened mouth, short and fat legs, tiny feet, a protuberant belly, chubby hands with dimples at the knuckles, sagging shoulders, and a short neck. His eyes were small, dark, frightened, distrustful, and insecure, as if asking permission for his actions.

5

Descriptions of him penned by historians usually disparage him.

According to Luiz Norton: “He was physically grotesque and his sickly obesity gave him the air of a peaceful dullard.”

6

According to Pandiá Calógeras:

Â

He was darling, but also lovingly and tolerantly dismissed for his weakness and cowardice. Nobody paid attention to his opinion, and this led him to hide his feelings, seeking victory by postponing solutions, inciting his advisors against each other, ministers thus opposing their colleagues. He achieved the realization of his intentions through tremendous apathy and procrastination. He triumphed by tiring his adversaries.

7

According to LÃlia Schwarcz: “He was lackluster and had no active voice.”

8

According to Oliveira Martins: “He had attacks of vertigo and attacks

of melancholy because he suffered from hemorrhoids. His ill health yellowed his flaccid visage, from which hung that famous lifeless pout, peculiar to the Bourbons.”

9

According to de Oliveira Lima, he was: “Short, fat . . . [with] the small hands and feet of the aristocracy, overly vulgar thighs and legs much too thick for his body, and above all a round face lacking majesty or any distinction, from which loomed the thick and dangling lower lip of the Habsburgs.”

10

He ascended to power accidentally after his mother, Queen Maria I, went mad and his older brother, José, heir presumptive, died of smallpox. In 1792, when it was confirmed that his mother was incurably mad, he assumed power provisionally with the support of the State Assembly, composed of nobles, military leaders, and representatives of the Church. In 1799, he became prince regent, which made him a king without a crown. His ascension took place in 1816, a year after his mother died and eight years after arriving in Rio de Janeiro. With his infamously indecisive and fearful personality, he governed Portugal during one of the most turbulent periods in the history of European monarchies.

Despiteâor perhaps because ofâthe turbulence, João suffered periods of deep depression. In the first major bout, recorded in 1805, he distanced himself completely from public life and from participation in the court. People thought that he had gone mad like his mother. “He had no wish to hunt or to ride horses, and turned to a completely sedentary existence,” writes Ãngelo Pereira. “His neurological condition facilitated a nervous breakdown, at this time poorly understood, which was confused with an attack of alienation. He had vertigo and outbursts of extreme anxiety.” He moved from the Palace of Queluz, where he lived with his family, to the Palace of Mafra, in the company of friars. Thereafter he isolated himself even further, moving to the royal family's manor in Vila Viçosa, in the region of Alentejo. Thinking her husband demented, Princess Carlota tried to have him removed from power and assume control of the state herself. Alerted by his doctor, Domingos Vandelli, João returned to Lisbon in time to block the coup. From then on, husband and wife lived separately.

11

Responsible for his education since childhood, priests surrounded the prince regent in the Palace of Mafra. He adored sacred music and detested

physical activity. “He was brought up far away from active, happy, strong and sanguine men, who loved to live life,” writes Pedro Calmon.

12

Profoundly religious and influenced by the Church, the prince attended mass every day. General Junot, commander of the French troops who invaded Portugal, described him to Charles de Talleyrand, French minister of foreign relations, as “a weak man, suspicious of everyone and everything, conscientious of his authority but unable to command respect. He is dominated by priests, and can only act under the coercion of fear.”

13

The prince's love life was mediocre at best. He married Carlota Joaquina under dynastic obligation. They had nine children, with whom he lived very briefly under the same roof. His only true love lingers in the history books as an obscure tragedy. At age twenty-five, living in Portugal and already married, Prince João became enamored of Eugênia José de Menezes, one of his wife's maids of honor.

14

Eugênia was granddaughter of Pedro, fourth marquis of Marialva, and daughter of Rodrigo José Antonio de Menezes, first count of Cavaleiros and Princess Carlota's head steward. Eugênia was born in 1781 when her father was governor of Minas Gerais. In May 1803, still unmarried, she became pregnant. Suspicions understandably fell on the prince regent, who had had amorous encounters with her through the combined machinations of a court priest and Dr. João Francisco de Oliveira, head physician of the army, himself married with children.

After discovering that Eugênia was pregnant, Oliveira quickly decided to sacrifice his own reputation to save the prince regent: He left his wife and children in Lisbon and fled with Eugênia to Spain, abandoning her in Cádiz. The nuns of the Conceição de Puerto de Santa Maria convent took her under their wing and helped her give birth to her daughter. From there, Eugênia moved to two other religious convents, dying in Portalegre on January 21, 1818, after the prince regent had been crowned king in Rio de Janeiro. During this entire period, João paid all of her expenses. Dr. Oliveira, after leaving Eugênia in Spain, fled to America and then to England where, according to Portuguese historian Alberto Pimentel, he reunited at last with the family he had abandoned in Portugal. In 1820, King João granted Dr. Oliveira the distinction of the Order of Christ and named him the head of Portuguese affairs in London.

15

It remains João's only known extramarital affair. In Brazil, he proved himself an even more solitary monarch than he had been in Portugal. His marriage to Carlota Joaquina, already unraveling since 1805, became an explicit separation in Rio de Janeiro. While D. João went to live in the Quinta de Boa Vista, Carlota preferred to live on an estate near Botafogo. They interacted with each other only according to protocol, in public ceremonies, masses, and concerts in the Royal Chapel.

Few historians risk entering into the details of João's personal life. Two of them, Tobias Monteiro and Patrick Wilcken, point to evidence that, in the absence of his wife, he maintained homosexual relationsâmore out of convenience than from convictionâwith Francisco Rufino de Sousa Lobato, one of the royal valets. Monteiro suggests that Rufino's duties included regularly masturbating the king. A friar who is identified only as Father Miguel had observed, against his intentions, intimate scenes between the king and his servant on the Santa Cruz ranch at the Summer Palace. After this episode, the friar was transferred to Angola, but before leaving he left written testimony of what he had witnessed.

16

It is possible that much of this resulted from palace intrigues, but Rufino received generous sums of money and promotions on various occasions in gratitude for his services. At the end of the Portuguese court's interlude in Brazil, Rufino had become: viscount of Vila Nova da Rainha, royal councilor, chamberlain, the king's personal treasurer, secretary of the Casa do Infantado, deputy secretary of the Mesa de Conscienca e Ordens in Brazil, and governor of Fortaleza de Santa Cruz.

17

Francisco Rufino was the third of four brothers of the Sousa Lobato family that accompanied João to Brazil in 1808. The others were Matias Antonio, Joaquim José and Bernardo Antonio. All four served as valets and personal assistants to the prince. Two also took part in the State Assembly, the highest advisory body to the king. Their relationship with the prince regent caused much gossip in Rio de Janeiro. Carlota Joaquina attributed to them “the disgraces of Portugal” during her husband's government, her secretary José Presas recounts. “The Prince always gives himself over to his favorites and courtiers, and he has done no more than aggrandize them, to the detriment of the kingdom and general discontent, as is the case today with the Lobatos,” she said to him.

18

Historian Vieira Fazenda recounts that Matias Antonio, given the title of baron and later viscount of Magé, lived in the City Palace, next to the São José Church, in a room contiguous to João's. He helped the king undress and accompanied him in the reading of the breviary before going to sleep. He stood by the king's side during nights of thunder and lightning.

19

Prussian traveler Theodor von Leithold, arriving in Brazil in 1819, confirmed João's fear of thunder. “If the King does not feel well, if he nods off or if there comes to pass a storm, which produces a strong reaction in him, he shuts himself in his chambers and receives no one,” he wrote, explaining the cancelation of a ceremony at the Palace of São Cristovão.

20

João referred to himself always in the third person: “Your Majesty wants to eat,” “Your Majesty wants to go for a walk,” “Your Majesty wants to sleep.”

21

A methodical man, he obsessively and rigorously repeated his daily routines. “D. João VI was a man of habits,” related the painter Manuel Porto Alegre. “If he slept once in a certain place, he would never want to sleep in another, taking things to the point where he would not allow that the bed remained more or less near the wallâit had to be right up against it. Any small change that was attempted would make him suspicious and irksome with whoever made it.”

22

This extreme aversion to change included his own apparel. In contrast to the showy kings of France and Spain who preceded him, João dressed badly. He wore the same clothes every day and refused to change them even when he stained or ripped them. “His usual outfit was a broad, greasy jacket made of old corduroy, threadbare at the elbows,” according to Pedro Calmon. In the pocket of this jacket, the king carried grilled and buttered boneless chickens that he devoured between meals.

23

“Horrified of new clothes, the King stuffed himself in the same ones from the evening before, which each day withstood less and less the pressure of his startlingly chubby thighs and buttocks,” adds Tobias Monteiro. “The servants noticed the rips, but nobody dared to tell him. They took advantage of his siestas, and sewed his pants while he slept in them.”

24