1812: The Navy's War (41 page)

Seeing the

Niagara

hesitating, the

Queen Charlotte

moved up to support the

Detroit

in clobbering the

Lawrence

. Early in the action, the

Queen Charlotte

’s captain, Lieutenant Robert A. Finnis, was killed, and his second, Acting Lieutenant Thomas Stokoe, was struck senseless by a splinter. Provincial Lieutenant Robert Irvine, an enthusiastic but inexperienced fighter, took command. Losing Finnis was a severe blow to Barclay, but Irvine continued to pummel the

Lawrence

. Perry was receiving fire from both of Barclay’s large ships and the

Hunter

as well.

Niagara

hesitating, the

Queen Charlotte

moved up to support the

Detroit

in clobbering the

Lawrence

. Early in the action, the

Queen Charlotte

’s captain, Lieutenant Robert A. Finnis, was killed, and his second, Acting Lieutenant Thomas Stokoe, was struck senseless by a splinter. Provincial Lieutenant Robert Irvine, an enthusiastic but inexperienced fighter, took command. Losing Finnis was a severe blow to Barclay, but Irvine continued to pummel the

Lawrence

. Perry was receiving fire from both of Barclay’s large ships and the

Hunter

as well.

Whatever Elliott’s motives in remaining apart from the fighting, the men aboard Perry’s flagship were furious with him. The

Lawrence

, the

Caledonia

, and the two schooners ahead had to withstand the full fury of Barclay’s heavy ships. For an excruciating two hours, Perry kept struggling against great odds, his ship being torn to pieces and his men being killed and wounded wholesale. Within two hours twenty-two men and officers lay dead on the

Lawrence

’s decks, along with sixty-six wounded. Every gun was dismounted and their carriages knocked to pieces, every strand of rigging was cut off, and mast and spars were shot and tottering; the entire ship was a wreck. “Every brace and bowline being soon shot away, she became unmanageable, not withstanding the great exertions of the sailing master,” Perry wrote. “In this situation, [we] sustained the action upwards of two hours, within canister distance, until every gun was rendered useless, and the greater part of

Lawrence

’s crew either killed or wounded.”

Lawrence

, the

Caledonia

, and the two schooners ahead had to withstand the full fury of Barclay’s heavy ships. For an excruciating two hours, Perry kept struggling against great odds, his ship being torn to pieces and his men being killed and wounded wholesale. Within two hours twenty-two men and officers lay dead on the

Lawrence

’s decks, along with sixty-six wounded. Every gun was dismounted and their carriages knocked to pieces, every strand of rigging was cut off, and mast and spars were shot and tottering; the entire ship was a wreck. “Every brace and bowline being soon shot away, she became unmanageable, not withstanding the great exertions of the sailing master,” Perry wrote. “In this situation, [we] sustained the action upwards of two hours, within canister distance, until every gun was rendered useless, and the greater part of

Lawrence

’s crew either killed or wounded.”

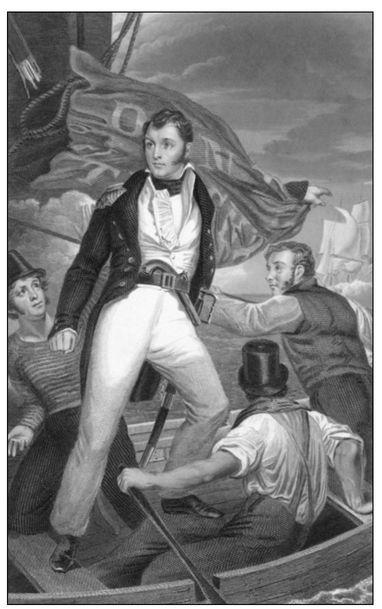

Miraculously, Perry himself was unscathed, and he refused to surrender. But he had nothing more to fight with; not another gun could be worked or manned. Instead of hauling down his colors, however, he had a brilliant inspiration—remove his flag to the untouched

Niagara

. He placed the crippled

Lawrence

in the capable hands of First Lieutenant John Yarnall and took his private flag displaying Captain Lawrence’s inspirational words into the only small boat left on the

Lawrence

. With his younger brother, twelve-year-old Midshipman James Alexander Perry—also unscathed—Perry rowed toward the

Niagara

.

Niagara

. He placed the crippled

Lawrence

in the capable hands of First Lieutenant John Yarnall and took his private flag displaying Captain Lawrence’s inspirational words into the only small boat left on the

Lawrence

. With his younger brother, twelve-year-old Midshipman James Alexander Perry—also unscathed—Perry rowed toward the

Niagara

.

In a few minutes, Yarnall, in order to save what was left of the crew, struck his colors, while Perry rowed furiously to reach the

Niagara

, determined to fight on. When he arrived, Elliott—no doubt anxious to get away—volunteered to leave the ship and bring the schooners, which had been kept astern by the lightness of the wind, into closer action. Perry agreed. In the next instant he looked back and saw that Yarnall had lowered the

Lawrence

’s flag. But Barclay, whose ship had also suffered grievously, could not take possession of her, and circumstances soon permitted the

Lawrence

’s flag to again be hoisted. Barclay later described the

Detroit

as a “perfect wreck.” His first lieutenant, Garland, was mortally wounded, and Barclay himself had been so severely injured just before Yarnall surrendered that he had to be carried below, leaving the

Detroit

in the hands of Provincial Lieutenant Francis Purvis.

Niagara

, determined to fight on. When he arrived, Elliott—no doubt anxious to get away—volunteered to leave the ship and bring the schooners, which had been kept astern by the lightness of the wind, into closer action. Perry agreed. In the next instant he looked back and saw that Yarnall had lowered the

Lawrence

’s flag. But Barclay, whose ship had also suffered grievously, could not take possession of her, and circumstances soon permitted the

Lawrence

’s flag to again be hoisted. Barclay later described the

Detroit

as a “perfect wreck.” His first lieutenant, Garland, was mortally wounded, and Barclay himself had been so severely injured just before Yarnall surrendered that he had to be carried below, leaving the

Detroit

in the hands of Provincial Lieutenant Francis Purvis.

Figure 17.1: Oliver Hazard Perry transfers from his flagship

Lawrence

to continue the Battle of Lake Erie aboard the

Niagara

(courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Collection at Hyde Park, New York).

Lawrence

to continue the Battle of Lake Erie aboard the

Niagara

(courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Collection at Hyde Park, New York).

At 2:45 Perry made the signal for “closer action” and immediately set after the British squadron in the undamaged

Niagara

. His luck continued to hold as the wind picked up, allowing him to reach his targets in fifteen minutes. “I determined to pass through the enemy’s line; bore up, and passed ahead of their two ships and a brig,” he wrote in his report, “giving a raking fire to them from the starboard guns, and to a large schooner and sloop from the larboard side, at half-pistol shot distance. The smaller vessels at this time, having got within grape and canister distance, under the direction of Captain Elliott, and keeping up a well-directed fire, the two ships, a brig, and schooner surrendered, a schooner and a sloop making a vain attempt to escape.”

Niagara

. His luck continued to hold as the wind picked up, allowing him to reach his targets in fifteen minutes. “I determined to pass through the enemy’s line; bore up, and passed ahead of their two ships and a brig,” he wrote in his report, “giving a raking fire to them from the starboard guns, and to a large schooner and sloop from the larboard side, at half-pistol shot distance. The smaller vessels at this time, having got within grape and canister distance, under the direction of Captain Elliott, and keeping up a well-directed fire, the two ships, a brig, and schooner surrendered, a schooner and a sloop making a vain attempt to escape.”

The victorious Perry now returned to the stricken

Lawrence

. “Every poor fellow raised himself from the decks to greet him with three hearty cheers,” Sailing Master William Taylor reported. “I do not hesitate to say there was not a dry eye on the ship.”

Lawrence

. “Every poor fellow raised himself from the decks to greet him with three hearty cheers,” Sailing Master William Taylor reported. “I do not hesitate to say there was not a dry eye on the ship.”

It was over. Perry’s courage, and his incredible luck, had won the day—in spite of Elliott’s treachery. “We have met the enemy and they are ours,” Perry wrote to General Harrison. His words, like Captain Lawrence’s “Don’t give up the ship,” would become immortal. To Secretary Jones he wrote, “It has pleased the Almighty to give to the arms of the United States a signal victory over their enemies on this Lake.” Perry’s triumph would have far-reaching consequences. It opened the way for the United States to regain the entire northwest territory lost by General Hull, and it effectively ended the alliance between the Indians and Great Britain. “[Perry] has immortalized himself,” Commodore Chauncey wrote to Jones. Indeed he had.

Perry made certain that the severely wounded Barclay was well cared for, probably saving his life. In his report on the defeat, Barclay wrote that having the weather gauge gave Perry an edge by allowing him to choose his position and distance, which had an adverse effect on the ability of the

Queen Charlotte

and the

Lady Prevost

to make more effective use of their carronades. Barclay’s greatest handicap, however, was manning. “The greatest cause of losing His Majesty’s Squadron on Lake Erie,” he wrote to Yeo, “was the want of a competent number of seamen.” His criticism of Yeo’s management could not have been plainer, and it was deeply felt. Prevost agreed with Barclay. He wrote to Earl Bathurst, the secretary of state for war and the colonies, that Yeo had appropriated for his own use on Lake Ontario all the officers and seamen sent from England, leaving Barclay to make do entirely with soldiers.

Queen Charlotte

and the

Lady Prevost

to make more effective use of their carronades. Barclay’s greatest handicap, however, was manning. “The greatest cause of losing His Majesty’s Squadron on Lake Erie,” he wrote to Yeo, “was the want of a competent number of seamen.” His criticism of Yeo’s management could not have been plainer, and it was deeply felt. Prevost agreed with Barclay. He wrote to Earl Bathurst, the secretary of state for war and the colonies, that Yeo had appropriated for his own use on Lake Ontario all the officers and seamen sent from England, leaving Barclay to make do entirely with soldiers.

Perry’s stunning, wholly unexpected triumph electrified the country. Elliott’s duplicity was overlooked amid the celebrating. Lieutenant Yarnall, however, wrote a letter on September 15 to the Ohio newspapers condemning Elliott, but his complaints were drowned out by the widespread acclaim for Perry. He was the man of the hour, lionized everywhere, and no more so than in Washington, where President Madison desperately needed a victory.

AFTER BARCLAY’S DEFEAT, General Proctor knew he had to evacuate Fort Malden immediately and march east along the Thames River toward Burlington at the head of Lake Ontario, where he’d have protection not only from the Americans but from his Indian allies. Proctor’s supplies had nearly run out, and most of his heavy guns had been on the

Detroit

, which Perry had captured, along with two hundred of Proctor’s best soldiers.

Detroit

, which Perry had captured, along with two hundred of Proctor’s best soldiers.

Tecumseh strenuously objected to retreating. He wanted to remain at Fort Malden and have a showdown with General Harrison, his longtime foe. But Proctor was convinced that he had to escape as quickly as possible. Since he had no supplies, and none could reach him, he thought staying at Amherstburg was suicidal. For Tecumseh, however, abandoning Amherstburg and Detroit meant leaving all the Indians of the Northwest to the mercy of the voracious Americans. The British had deserted their Indian allies before—most notably after the American Revolution but also in the Jay Treaty—with disastrous consequences for all the tribes. To appease Tecumseh, Proctor made a promise (which he never meant to keep) to make a stand at the forks of the Thames. Having no alternative, Tecumseh was forced to go along.

Feeling more and more anxious as the days passed, Proctor retreated as fast as he could, worrying all the time that Harrison would be right on his heels. By September 23 Proctor had evacuated to Sandwich and burned Amherstburg and Detroit. Four days later, he began to panic when Harrison, working closely with Perry, started debarking thousands of troops at Amherstburg. Harrison’s army included troops from Fort Meigs under General McArthur, and 3,000 Kentucky militiamen led by Governor Isaac Shelby, a hero of the Battle of King’s Mountain during the War of Independence. At the same time, Kentucky congressman Richard M. Johnson, one of the War Hawks, was riding to Detroit at the head of 1,000 mounted infantrymen.

Harrison pursued the retreating Procter along the Thames River, and Perry, with a strong contingent of tough sailors, accompanied him. Tecumseh reluctantly stayed with Procter, but he was disgusted with him, as indeed were Proctor’s own officers and men, who were unnerved by his panic. Many of Tecumseh’s warriors had already melted away into the forest, along with British deserters.

On October 5 Harrison caught up with the enemy near Moravian Town on the Thames, fifty miles east of Detroit. By then Proctor’s force had dwindled to 1,000, including 500 Indians. Harrison had 3,500 men, including Johnson’s mounted infantry. Harrison had left most of his regulars to garrison Amherstburg and Detroit. What became known as the Battle of the Thames now ensued. It was over in half an hour. Given the disparity of forces and Proctor’s poor leadership, a British defeat was inevitable. Tecumseh fought to the death. When he fell, any chance—admittedly slim to begin with—for the Indians to preserve their ancient way of life in the Northwest, or indeed east of the Mississippi, died with him.

Having always been most concerned with saving himself, Proctor managed to avoid surrender and, in unseemly haste, escaped from the battlefield with one quarter of his men to the safety of Burlington at the head of Lake Ontario. His performance did not go unnoticed by his superiors. A court-martial convicted him of misconduct and deprived him of his rank and pay for six months, after which the British army found no further use for him.

For Governor Shelby the victory was the realization of a dream that Kentucky and the entire Northwest had had since the days of Daniel Boone—the end of Indian and British power in those vast regions and the undisputed ascendancy of the United States. America was now free to exploit the entire territory unimpeded. Since Shelby had accomplished his great objective, he took his Kentuckians home. Harrison wanted to press on to Lake Ontario and play an important part in the general movement to wrest all of Upper Canada from the British. But most of his force was composed of Kentucky militiamen, and when they returned home, he had to fall back on Detroit and Amherstburg.

FOLLOWING THE BATTLE of the Thames, Perry, still angry with Chauncey, requested a transfer to Rhode Island. A grateful administration allowed him this indulgence. On September 29 Secretary Jones sent Perry a letter telling him he was promoted to captain and approving his transfer back to Newport. Chauncey was furious about the new assignment but not about the promotion, which he admitted was richly deserved. He wrote an angry letter to Jones, who understood Chauncey’s objections but did not change his mind about moving Perry. Jesse Elliott became the new commandant on Lake Erie.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Attack on Montreal

I

N THE SUMMER of 1813, at the same time that Perry and Harrison were planning to secure the Northwest, Madison was preparing to attack Kingston and Montreal, something he had intended to do back in the spring, before Dearborn and Chauncey had talked him out of it. Even if he succeeded, the key British strongholds at Quebec and Halifax would remain, but taking Upper Canada would strengthen the president’s diplomatic hand immeasurably. With Napoleon in trouble, seizing Canada, or a substantial portion of it, was the only way Madison could gain enough leverage to move Liverpool and his colleagues. Nothing had been heard from the British about negotiations, although it was clear they were not rushing to accept the czar’s offer to mediate. The operations against Canada were therefore critical. At the moment, all the president had to bargain with was Amherstburg.

N THE SUMMER of 1813, at the same time that Perry and Harrison were planning to secure the Northwest, Madison was preparing to attack Kingston and Montreal, something he had intended to do back in the spring, before Dearborn and Chauncey had talked him out of it. Even if he succeeded, the key British strongholds at Quebec and Halifax would remain, but taking Upper Canada would strengthen the president’s diplomatic hand immeasurably. With Napoleon in trouble, seizing Canada, or a substantial portion of it, was the only way Madison could gain enough leverage to move Liverpool and his colleagues. Nothing had been heard from the British about negotiations, although it was clear they were not rushing to accept the czar’s offer to mediate. The operations against Canada were therefore critical. At the moment, all the president had to bargain with was Amherstburg.

Unfortunately, Madison was sick for five weeks in June and July, suffering a debilitating illness (similar to the one that had struck him the previous summer). Dolley again feared for his life. Direction of the war fell to the president’s department heads, and they were agreed that putting off the attacks on Kingston and Montreal earlier in the year had been a huge mistake. Secretary Armstrong wanted to make up for it now by striking both places during the late summer. He hoped that by then Commodore Chauncey would have naval supremacy on Lake Ontario. Secretary Jones, not a great admirer of Armstrong, nevertheless agreed with the plan and did everything he could to support Chauncey. But time was running out; winter in that part of Canada arrived in late October.

Other books

Wishes and Tears by Dee Williams

Cross of Vengeance by Cora Harrison

The Sookie Stackhouse Companion by Charlaine Harris

Assassin's Heart by Sarah Ahiers

Tease by Immodesty Blaize

Free Agent by Roz Lee

Burning Intensity by Elizabeth Lapthorne

What Laurel Sees: a love story (A Redeeming Romance Mystery) by Susan Rohrer

Bound With Pearls by Bristol, Sidney

The Snow Walker by Farley Mowat