(4/13) Battles at Thrush Green

Read (4/13) Battles at Thrush Green Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrush Green (Imaginary Place), #Pastoral Fiction, #Country Life - England

| Battles at Thrush Green | |

| Thrush Green [4] | |

| Miss Read | |

| Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (1975) | |

| Rating: | ★★★★☆ |

| Tags: | Fiction, Country Life - England, Thrush Green (Imaginary Place), Pastoral Fiction Fictionttt Country Life - Englandttt Thrush Green (Imaginary Place)ttt Pastoral Fictionttt |

Product Description

Feelings are running high in the Cotswold village of Thrush Green. The rector’s plan for the neglected churchyard doesn’t meet with universal approval; there is a clash of personalities at the local school; and someone has returned to the village after an absence of fifty years.

About the Author

Miss Read is the pseudonym of Mrs. Dora Saint, a former schoolteacher beloved for her novels of English rural life, especially those set in the fictional villages of Thrush Green and Fairacre. The first of these, Village School, was published in 1955, and Miss Read continued to write until her retirement in 1996. In the 1998, she was awarded an MBE, or Member of the Order of the British Empire, for her services to literature. She lives in Berkshire.

Battles at Thrush Green

Miss Read

Illustrated by J. S. Goodall

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston • New York

First Houghton Mifflin paperback edition 2008

Copyright © 1975 by Miss Read

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions,

Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South,

New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Read, Miss

Battles at Thrush Green.

I. Title.

PZ

4.

S

132

BAT

3 [

PR

6069.

A

42] 823'.9'14 75-33794

ISBN

0-395-24290-8

ISBN

978-0-618-88441-4 (pbk.)

Printed in the United States of America

DOC

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Norah

For Times Remembered

With Love

CONTENTS

Part One

Alarms and Excursions

1 Albert Piggott Is Overworked 12

2 Miss Fogerty Is Upset 23

3 Dotty Harmer's Legacy 32

4 Driving Trouble 45

5 Skirmishes At The Village School 54

6 Doctor Bailey's Last Battle 64

Part Two

Fighting Breaks Out

7 The Rector Is Inspired 78

8 Dotty Causes Concern 92

9 Objections 101

10 Problems At Thrush Green 112

11 Winnie Bailey's Private Fears 122

12 The Summons 133

13 A Question Of Schools 143

14 Dotty's Despair 154

Part Three

The Outcome of Hostilities

15 The Sad Affair Of The Bedjacket 166

16 Getting Justice Done 176

17 The Rector In Action 187

18 A Cold Spell 199

19 Dotty In Court 210

20 Peace Returns 227

Part One

Alarms and Excursions

1 Albert Piggott Is Overworked

A

T

a quarter to eight one fine September morning, Harold Shoosmith leant from his bedroom window and surveyed the shining face of Thrush Green.

The rising sun threw grotesquely elongated shadows across the grass. The statue of Nathaniel Patten cast one a dozen times its own length, with the head and shoulders at right angles to the rest, where it was thrown against the white palings next door to "The Two Pheasants."

The shabby iron railings round the churchyard made cross-hatchings on the green, and the avenue of chestnut trees, directly in front of Harold's window, formed a shady tunnel with a striped floor of sunshine and shadow.

The view filled Harold Shoosmith with deep contentment. This was the place for retirement! After years in Africa, moving from one post to another, each hotter and more humid than the last, he had come home to roost at Thrush Green, the birthplace of Nathaniel Patten, whose missionary work he had so much admired, and whose memorial he had been instrumental in establishing.

But no living figures were apparent on this bright morning, with the exception of the Youngs' old spaniel Flo, who was ambling about examining the trees in the avenue in a perfunctory fashion. Nevertheless, the sound of distant whistling alerted Harold.

Someone in the wings was about to enter the empty stage, and very soon the stout figure of Willie Bond, one of Thrush Green's postmen, emerged from the lane, which leads to Nod and Nidden, and propped his bicycle against the hedge.

Tightening the belt of his dressing gown, Harold Shoosmith descended the stairs to greet his first caller.

'You gotter mushroom as big as a nouse in your 'edge,' announced Willie, handing in half a dozen letters.

'Let's see,' said Harold, following him down the path. Sure enough, at the foot of his hawthorn hedge, stood a splendid specimen, as big as a saucer, but young and beautiful. Two or three fine pieces of grass criss-crossed its satin top where it had pushed its way into the world and, underneath, the gills were rosy pink and unbroken.

'Do fine for your breakfast,' said Willy, putting one foot on the pedal of his bicycle.

'Too much for me,' said Harold. 'Why don't you take it? After all, you found it.'

Willie shook his head.

'Never touches 'em. Them old things are funny. My auntie, down the mill, she died after havin' a dish of them for breakfast.'

'Surely she must have eaten toadstools by mistake?'

'Maybe. But she died anyway.'

He mounted his machine and began to weave away.

'Mind you,' he called back, 'she'd had dropsy for five years, but we always reckon it was the mushrooms what done for her in the end.'

Harold bent and retrieved the mushroom. The fragrance, as it left the ground, made him wonder, for one brief moment, if he could bother to cook some of it with a couple of rashers for his breakfast, as Willie had advised.

But he decided against it and, returning to the kitchen, set about making his usual coffee-and-toast repast, using the upturned mushroom as decoration for the breakfast table.

His morning mail was unremarkable. Two bills, one receipt, a bulky and unsolicited package from 'Reader's Digest' which must have cost a pretty penny to produce and was destined for the wastepaper basket unread, and a postcard from his old friend and neighbour Frank Hurst and his wife Phil, posted in Italy two weeks before, and extolling the beauties of the scenery.

It was while he was sipping his second cup of coffee, and wondering idly why literary men always seemed to write such a vile hand, that the door burst open to reveal Betty Bell, his exuberant domestic help. As always, she was breathless and smiling. She might just have galloped up the steep hill from Lulling non-stop, but in fact, as Harold well knew, she had simply wheeled her bicycle from the village school next door where she had been 'putting things to rights' for the past half-hour.

'How's tricks then?' enquired Betty, struggling out of her coat. 'All fine and dandy? Wantcher study done first or the bed? Laundry comes today, you know.'

Harold did his best to look alert and to switch to the faster tempo of activity which Betty's arrival always occasioned.

'Study, I think. I've still to dress and shave. I'm rather behind this morning.'

'Well, rime's your own, now you're retired.'

Her eye lit upon the mushroom.

'What a whopper! Where'd you find that?'

'Willie Bond found it. It was growing just the other side of the hedge. Would you like it?'

Betty Bell gave a shudder.

'I wouldn't touch it if it was the last thing on earth to eat. Not safe, them things. Why, my old auntie died of eating mushrooms. Honest, she did!'

Betty's eyes grew round with awe.

'What an extraordinary thing,' exclaimed Harold. 'So did Willie's aunt!'

'Nothing extraordinary about it,' replied Betty, rummaging in the dresser drawer for a clean duster. 'She was my auntie too. Me and Willie Bond's cousins.'

She swept from the room like a mighty rushing wind, leaving Harold to ponder on the ever-enthralling complications of village life.

Some time later, Harold emerged from his front door bearing the mushroom in a paper bag. Behind him the house throbbed with the sound of the vacuum cleaner and Betty Bell's robust contralto uplifted in song.

It was good to be away from the noise. The air was fresh. A light breeze shook a shower of lemon-coloured leaves from the lime trees, and ruffled Harold's silver hair, as he set off across the grass to the rectory. He had remembered that the Reverend Charles Henstock and his wife Dimity were both fond of mushrooms.

On his way he encountered the sexton of St Andrew's. The church stood at the south-western corner of Thrush Green, and Albert Piggott's house was placed exactly opposite it and next door to "The Two Pheasants." Albert divided his time, unequally, between the two buildings.

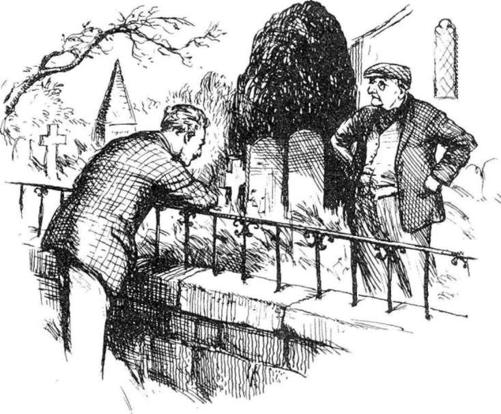

The sunshine and serenity of the morning were not reflected in Albert's gloomy face. Hands in pockets, he was mooching about among the tombstones, kicking at a tussock of grass now and again and muttering to himself.

'Good morning, Piggott,' called Harold.

'A good morning for some, maybe,' said Albert sourly, approaching the railings. 'But not for them as 'as this sort of mess to clear up.'

Harold leant over the railings and surveyed the graveyard. Certainly there were a few pieces of paper about, but to his eye it all looked much as usual.

'I suppose people throw down cigarette boxes and so on when they come out of the pub,' he remarked, 'and they blow over here. Too bad when there's a litter box provided.'

'It's not the paper as worries me,' replied Albert. 'It's this 'ere grass. Since my operation, I can't do what I used to do.'

'No, no. Of course not,' said Harold, assuming an expression of extreme gravity in deference to Albert's operation. Thrush Green was learning to live with Albert Piggott's traumatic experience, as related by him daily, but was finding it a trifle exhausting.

'Take a look at it,' urged Albert. 'Take a proper look! What chance is there of pushin' a mower up these 'ere paths with the graves all going which-way? One time I used to scythe it, but Doctor Lovell said that was out of the question. "Out of the question, Piggott," he said to me, same as I'm saying to you now. "Out of the question." His very words.'

'Quite,' said Harold.

'And take these railings,' went on Albert, warming to his theme. 'When was they put up, eh? You tell me that. When was they put 'ere?'

'A good while ago,' hazarded Harold.

'For Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee, that's when,' said Albert triumphantly. 'Not 'er Diamond one, but 'er

Golden

one! That takes you back a bit, don't it? Won't be long afore these railings is a 'undred years old. Stands to reason they're rusted. 'Alf of'em busted, and the other 'alf ought to be pulled out. There was always this nice little stub wall of dry stone. That don't wear too bad, but these 'ere railings 'as 'ad it!'