97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement (29 page)

Read 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement Online

Authors: Jane Ziegelman

Tags: #General, #Cooking, #19th Century, #History: American, #United States - State & Local - General, #United States - 19th Century, #Social History, #Lower East Side (New York, #Emigration & Immigration, #Social Science, #Nutrition, #New York - Local History, #New York, #N.Y.), #State & Local, #Agriculture & Food, #Food habits, #Immigrants, #United States, #Middle Atlantic, #History, #History - U.S., #United States - State & Local - Middle Atlantic, #New York (State)

Unlike her sisters in the factories, the home worker fell beyond the reach of protective labor laws that regulated the length of her workday along with her minimum wage. Her children were also unprotected. In the Old Country, children worked side by side with their fathers in the fields. In cities like New York, the moment they returned from school they went to work shelling hazelnuts or walnuts until deep into the night. During the rush seasons just before Christmas and Easter, they were kept home from school entirely.

In the eyes of middle-class America, the candy home worker was an ambiguous figure, equal parts victim and villain. Bullied and abused by greedy factory owners, she attracted support from social reformers like the National Consumer League, which advocated on her behalf. At the same time, the outworker was a threat to public safety, the foods that touched her hands contaminated by the same germs that flourished in her tenement home. Pasta, wine, matzoh, and pickles were also produced in the tenements, foods made by immigrants for immigrants. Candy, however, was different. While made by foreigners, it was destined for the wider public, available in the most exclusive uptown stores.

As middle-class Americans became aware of tenement candy workers, panic set in. Tenement-made candy, they surmised, was the perfect vehicle for transporting working-class diseases like cholera and tuberculosis from the downtown slums to the more pristine neighborhoods in Upper Manhattan. “Table Tidbits Prepared Under Revolting Conditions,” a story that ran in the

New York Tribune

in 1913, sounded the alarm:

Foodstuffs prepared in tenement houses? For whom? For you, fastidious reader and for everybody! A pleasant subject this for meditation. Slum squalor has been reaching uptown in many insidious ways. It was bad enough to think that the clothing one wore had been handled in stuffy rooms, where sanitary conditions and ventilation were deplorable…When it is learned, however, that many of the things actually eaten or put to the lips have been prepared by some poor slattern in indifferent or bad health and by more or less dirty tots of the slums amid surroundings that would cause humanity to hold its nose, a brilliant future looms up for some of the scourges scientists are busily endeavoring to stamp out.

10

An immigrant family shelling nuts at their kitchen table. This photo was used to demonstrate the unsanitary conditions that prevailed among tenement home workers.

Library of Congress

Stories like this one, brimming over in lurid details, enumerated the many sanitary breaches committed by the home worker. She was known, for example, to crack nuts with her teeth and pick them with her fingernails. At mealtime, picked nuts were swept to the side of the table, or removed to the floor or the bed. But most alarming of all, home workers performed their tasks in rooms shared by tuberculosis sufferers or children sick with measles. In some cases, the home worker was sick herself, like the consumptive woman who was too weak to leave her bed but somehow managed to go on with her work as a cigarette maker. The one detail consistently absent from these stories was mention of any documented illness linked to tenement-made goods. They may have occurred, but the looming threat posed by the home worker was more compelling than the actual risk.

While immigrant candy workers fed the national sweet tooth, in their own communities, Italian confectioners made sweets for their fellow countrymen. The more prosperous owned their own shops, or

bottege di confetti

, preparing the candy in large copper pots at the back of the store. Marzipan,

torrone

(a nougat-like candy made with egg whites and honey), and

panforte

, a dense cake made of honey, nuts, and fruit, were specialties of the confectioner’s art. The

confetti

shops also sold pastries like cannoli and

cassata

, an ornate Sicilian cake made with ricotta, candied fruit, sponge cake, and marzipan. In the months leading up to Easter, store owners created window displays of their gaudiest, most eye-catching sweets. Herds of marzipan lambs grazed in one corner of the window, beside a field of cannoli. Pyramids of marzipan fruits and vegetables, each crafted in fine detail, loomed in the background. Most eye-catching of all, however, were candy statues representing the main actors in the Passion story: a weeping Virgin Mary in her blue cloak; Christ in his loincloth staggering under the weight of the cross; Mary Magdalene; and even the heartless Roman soldiers brandishing their spears, all cast from molten sugar.

The Easter celebration was a family event centered on the home. More conspicuous occasions for candy consumption were the religious festivals held through the year in the streets of Little Italy. The

feste

were open-air celebrations in honor of a particular saint, each one connected with a town or village back home. Sponsored by fellow towns people, they combined religious observance in the form of a solemn procession with brass bands, fireworks, and public feasting, the exact nature of food determined by the immigrants’ birthplace. A Sicilian festival, for example, would include

torrone

, but not the kind made with egg whites. Sicilian

torrone

was a glossy nut brittle made with almonds or hazelnuts, a confection brought to Sicily by the Arabs. There was also

cubbaita

, or sesame brittle, another Arab sweet, and

insolde

, a Sicilian version of

panforte

. Below is a description of the foods, candy included, available at a 1903 festival held in Harlem, the uptown Little Italy, honoring Our Lady of Mount Carmel:

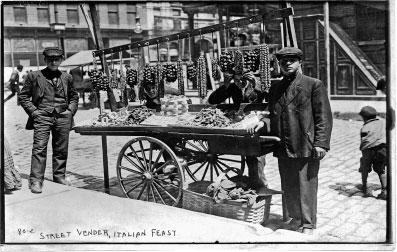

Nut peddler at an Italian street festival.

Library of Congress

The crowd is chiefly buying things to eat from street vendors. Men push through the masses of people on the sidewalks, carrying trays full of brick ice cream of brilliant hues and yelling “Gelati Italiani”—Italian ices. “Lupini,” the “ginney beans” of the New York Arab; “ciceretti,” the little roasted peas and squash seeds are favorite refreshments. Great ropes of Brazil nuts soaked in water and threaded on a string, or roasted chestnuts, strung in the same way, lie around the vendor’s neck. Boys carry long sticks strung with rings of bread. All manner of “biscuitini,” small Italian cakes, are for sale, frosted in gorgeous hues, chiefly a bright magenta cheerful to look upon but rather ghastly to contemplate as an article of food.

Boys at the door of bakeshops vociferate “Pizzarelli caldi”—hot pizzarelli. The pizzarello is a little flat cake of fried dough, probably the Neapolitan equivalent of a doughnut. They sell for a penny a piece. Sometimes the cook makes them as big as the frying pan, putting in tomato and cheese—a mixture beloved of all Italians. These big ones cost 15 cents, but there is enough for a taste all around the family. The bakers are frying them hot all through the feast. A certain cake made with molasses, and full of peanuts or almonds, baked in a long slab and cut in little squares, four or five for a cent, is much eaten. So is “coppetta,” a thick, hard white candy full of nuts; and the children all carry bags of “confetti,” little bright-colored candies with nuts inside. Here and there the sun flashes on great bunches of bright, new tin pails, heaped on the back and shoulders of the vendor: and the new pail bought and filled with lemonade passes impartially from lip to lip of the family parties lunching on the benches in Thomas Jefferson Park.

11

Below is a recipe for

croccante

, or almond brittle. It is adapted from

The Italian Cook Book

by Maria Gentile, published in 1919, among the earliest Italian cookbooks published in the United States.

C

ROCCANTE

3 cups blanched sliced almonds

2 cups sugar

1–2 tablespoons mildly flavored vegetable oil

1 lemon cut in half

Preheat to 400ºF. Liberally grease a baking tray with the vegetable oil and put aside. Spread almonds on a separate tray and toast in hot oven until golden, about 5 minutes. Heat sugar in a heavy-bottomed saucepan and cook until sugar has completely melted. Add almonds and stir. Pour hot mixture onto greased baking tray, using the cut side of the lemon to spread evenly. Allow to cool and break into pieces.

12

In the descriptive names that immigrants invented for the United States is a measure of what they expected to find. To Eastern European Jews, America was the

Goldene Medina

, or “Golden Land,” a place of extravagant wealth. For the Chinese immigrants who settled on the West Coast, America was “the gold mountain,” a reference to the California hills that would make them rich. Sicilians, by contrast, referred to America as “the land of bread and work,” an image of grim survival, comparatively speaking. To the Sicilian, however, bread was its own form of wealth. More than other Italians, Sicilians felt a special closeness to this elemental food, a “God-bequeathed friend,” in the words of Jerre Mangione, “who would keep bodies and souls together when nothing else would.”

13

The Sicilian respect for bread was rooted in a long history. From the sixteenth century forward, bread formed the axis of the peasant diet, sustaining—though just barely—generations of Sicilian field workers. The typical Sicilian loaf was made from a locally cultivated strain of wheat,

triticum durum

, which Arab settlers had brought to Sicily, along with almonds, lemons, oranges, and sugar, back in the ninth century. The wheat grew on giant estates called

latifundi

, and by the Middle Ages it covered most of Sicily’s arable land. Durum was a particularly hardy strain with a high protein content, producing a dense, chewy bread with a powerful crust. When mixed with water, it could be stretched into thin sheets that resisted tearing, making it ideal for pasta, too.

Peasants who worked all day in the field packed a hunk of bread and maybe an onion for their lunch. For dinner, there was bean soup, and yet more bread. As minimal as this sounds, the Sicilian pantry became even more spare during periods of famine, which in Sicily amounted to “a time without bread.” A Sicilian proverb recounted by Mary Taylor Simeti in

Pomp and Sustenance

sums it up beautifully:

If I had a saucepan, water, and salt,

I’d make a bread stew—if I had bread.

A loaf of bread for Sicilians embodied the basic goodness of life. Where we might say a person is “as good as gold,” a Sicilian says “as good as bread.” A piece of bread that fell to the ground was kissed, like a child with a scraped knee.

When Sicilians described America as the land of bread and work, they imagined a country without hunger, which, in their experience, was just as miraculous as a city paved in gold. One thing they never imagined, however, was that bread would fall into their hands like manna from heaven. Richard Gambino, describing the powerful work ethic that guided his Brooklyn neighborhood, remembers a phrase often repeated by the local men,

“In questa vita si fa uva,”

literally translated as, “In this life, one produces grapes.” In other words, each one of us has been put on this earth to be useful. Gambino also remembers his grandfather’s Sicilian friends holding up their calloused workers’ hands and saying

“America e icca,”

meaning “America is here—this is America.”

14

For the Sicilian, bread and work were locked together in a kind of dance that began early in life, the day the young Sicilian was old enough to contribute.

Sicilians carried their bread tradition to America, where it continued with certain necessary revisions. On Saturdays in Sicily, women did all their baking for the coming week, a way to preserve precious fuel. In cities like New York, the Italian laborer, now on his own, purchased his weekly ration each Saturday in Little Italy. Here, Italian peddlers sold loaves prepared expressly for the “diggers and ditchers,” immense crusty loaves nearly the size of a wagon wheel. Anyone who could not afford to buy their bread fresh, bought stale loaves, a special sideline of the retail bread trade controlled by women. Bread that was once thrown away was sold by the larger bakeries and retail houses to middlemen who, in turn, sold it to the peddlers, women who sat on the curbstone, their goods piled in a blanket beside them. As the immigrant’s finances swelled, his diet branched out in new directions. Pasta, eggs, and, eventually, meat diverted some of his affection for bread but never replaced it. In the Mangione household, bread was eaten with every course of the Sunday feast, except for the pasta. A bowl of soup without bread was bereft of its faithful companion. Meat without bread was considered sinful.