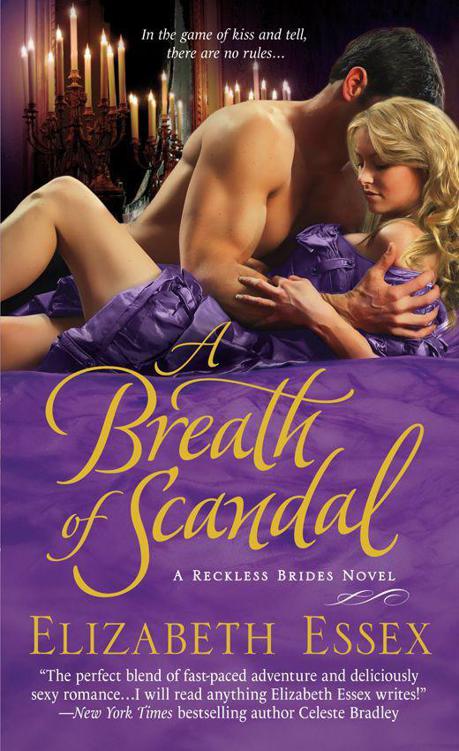

A Breath of Scandal: The Reckless Brides

Read A Breath of Scandal: The Reckless Brides Online

Authors: Elizabeth Essex

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Contents

Prologue

Wealdgate Village, Sussex

December 1814

It ought to have had the decency to rain.

If it had rained, the wet winter downpour might have been able to match the raw, aching pain of the day. If it had rained, the ominous, brooding gray clouds blanketing the sky might have been able to prepare her for the dripping misery of what was to come.

If it had rained, she might have been able to cry.

At her side, her sister wept soundlessly into her immaculate, embroidered lawn handkerchief. But Antigone Preston did not cry. She squared her shoulders and squinted her eyes against the insufferable brightness of the morning sun, and willed the heavens to open with a torrent of sorrow to match the tide of grief welling within her chest, and obliterate the scene laid out in front of her eyes in such precise, melancholy detail.

But nothing of the sort happened.

A few feet away, the vicar opened his book, and the ancient prayers for the dead rose from his mouth on ghostly clouds, evaporating with useless grace in the cold air of St. Bartholomew’s churchyard. “We brought nothing into this world, and it is certain we can carry nothing out. The Lord giveth and the Lord hath taken away.”

The Lord had taken Papa away—carried him off so suddenly one fine morning three days ago, she could still scarcely comprehend it. Without him, without his gentle logic and glad goodwill, Antigone couldn’t seem to think at all. She could only shut her eyes against the stark sunshine and rail against the serene heavens in heartbroken frustration.

Because instead of cloaking her sorrow in gray, weeping rain, the winter sun was a mocking abomination, shining in a sky so startlingly blue and crystalline in its brilliance, it hurt her head as much as it hurt what was left of her heart.

“I held my tongue, and spake nothing: I kept silence, yea, even from good words, but it was pain and grief to me.”

Everything was pain and grief to her. Every glistening blade of grass poking through the cold crust of snow crunching under her feet. Every curl of frosted breath that rose in the air from her mouth in brittle, aching relief. Every clump of earth that fell upon the wooden lid of the coffin with jarring, emphatic finality.

“Come ye blessed children of my Father, receive the kingdom prepared for you from the beginning of the world.”

Nothing was prepared for Antigone. Nothing. And she was not prepared in the least for life without Papa. None of them were.

When the service was at last done, the Reverend Mr. Martin came forward to offer what inadequate murmured solace he could at so very great a loss. The other mourners, a scattering of men who were Papa’s friends and country neighbors, were dispersing to find respite from the biting cold in the forgetful warmth and comfort of their own fires, and Antigone and her sister, Cassandra, were left to make their way home alone, across the fallow frozen fields to the small manor house on the northern edge of the village, as the insidious icy cold crept through the soles of their boots.

And still, Antigone did not cry.

Not even when her mother, in her own inconsolable grief over Papa’s death, betrayed Antigone’s trust in the most unexpected way possible, by betrothing her on the very day of her father’s funeral, to a rich man three times her age.

Antigone did not cry. She could not. She was too surprised.

Chapter One

There was nothing—no warning, no obvious sign from the heavens that her life would be upended. No deluge. No tremors. No helpful plague of locusts falling from the sky.

Only the bright winter sun, shining down upon the quiet house as if it were a normal day. As if everything at Redhill Manor were still the same.

But it wasn’t. Though the comfortably familiar entryway looked as it always had, with its rich-hued ancient Turkey carpet covering the wide floorboards, and its landscape painting of the hunting scene hanging over the marble console table against the wall, there was Papa’s umbrella, exactly where he had last left it, sprawled open against the corner of the table, a balm and a jarring reminder that no matter if everything looked the same, everything had changed with Papa’s death.

Every routine had been interrupted, every comfort already curtailed. The fire in the drawing room grate had not even been laid, let alone lit to take the aching chill from their bones. But no matter the enormity of their grief, life had to go on. And Antigone would have to be the one to carry on—to light at least some fires, to bargain with the butcher, and to plant the kitchen garden.

“Go on up.” Antigone urged her older sister toward the stairs. “I’ll send Sally up to you with something warming.”

Antigone should have accepted the wisdom of bowing to the convention that funerals were no place for gently bred ladies, and insisted Cassie stay home with Mama, instead of exposing her so cruelly in her grief. But Cassie, in her characteristic generosity, had not wanted Antigone to be alone, and Antigone, in her characteristic tenacity, had been absolutely adamant that Papa not be alone on this, his final journey from this life.

Cassie kissed her cold cheek, and with a light squeeze to her hand, left for the temporary sanctuary of her room upstairs. For Antigone there could be no sanctuary yet. There was too much to be done.

“Antigone?” Mama’s thin voice came from behind the open door of the morning room at the back of the house.

Antigone crossed the creaking floorboards of the hallway, thinking to find her mother still awash in grief, her eyes and nose red, and her hair untidy beneath her cap. Ever since the moment when Antigone had found Papa dead in his book room, sitting quietly in his chair, as if he had just closed his eyes to ponder whatever mathematical problem had been besetting him, her mama had lost herself in worry and dire predictions of woe.

“What is to become of us? Where is the money to come from?” Mama had wept and wailed, and ordered the fires put out, as though they could no longer afford fuel. As though Papa had been so thoughtless as to leave them destitute and insolvent. As though his estate were to be be entailed away and leave them at any moment without a home.

In the absence of any real knowledge of the state of their finances, Antigone had tried to calm her mother as best she could, but with Mama in such alarm, it had fallen to Antigone to see that things were done—to order fires lit, to make arrangements with the vicar and purchase black ribbons for their clothes, to write to Papa’s mathematical colleagues and collaborators at Cambridge University and in the Analytical Society, as well as the Royal Society, and inform his solicitor in Chichester. To carry on.

But in the green-walled morning room, the morning sun streaming through the east-facing windows revealed her mother looking not wild-eyed and disheveled, but beautifully dressed in a charcoal wool gown, not a hair out of place beneath a black lace cap, and without a trace of red in her eyes. She was receiving a visitor.

Lord Aldridge.

Antigone could not have been more surprised.

Lord Aldridge was a rather severe man Antigone knew only as the frosty master of the local hunt, a man who kept tight control of both the hunting field and his prized pack of hounds, kenneled at his estate, Thornhill Hall, some miles from the village. Antigone had often followed the progress of Thornhill Hunt from a distance, but had never hunted with his field, as ladies—especially brash young ladies on horses faster and more powerful than any other mount in the field—were actively discouraged from participating, if not banned outright. Antigone had never had more than a nodding—or more accurately, a frowning—acquaintance with the man.

Lord Aldridge had not been among the mourners at either the church or the graveyard. While Papa had been a gentleman—a mathematical scholar, a graduate and former fellow of the university of Cambridge, and a member of the prestigious Royal Society—the Preston family had been quite beneath Lord Aldridge’s entirely more lofty touch.

But instead of offering her his condolences as Antigone expected, what he offered, apparently, was his hand. Although he didn’t phrase it quite so romantically.

“My dear Miss Antigone,” he addressed her with polite formality from where he stood in front of the cold fireplace. “I have spoken to your mother, and it is all arranged. She has accepted my proposal for your fair hand, and it only remains for you to make me the happiest of men.”

Lord Aldridge could not have shocked her any more if he had struck her with his hunting whip—the burning feeling of astonished heat in her face had been about the same. In three short, emotionless sentences, he had declared himself to her with less animation than if he had been discussing the lay of a covert, and not the prospect of taking her to wife.

It is all arranged.

Any other twenty-year-old girl might have accepted his rather bloodless proposal gracefully. But Antigone Preston was not any other girl, and she was certainly no fool. She was her father’s daughter, and her quick and clever mind could find no logical reason for Lord Aldridge’s shockingly swift interest in making her his bride. She, of all people, who was more at home out of doors, riding her prized mare, or tromping through the woods in any weather than in a lord’s drawing room. She, who had neither beauty—she was no ogress, but Cassandra was the delicate, lavender-eyed beauty of the family, and Antigone’s plainer looks and ordinary blue eyes paled in comparison—nor fortune, nor any family connections from which he might profit in any way. And who was in mourning.

It was all absurd and strange, and completely impossible.

“You’re jesting with me,” she blurted with what she could summon for a laugh. Anything else was ridiculous.

“Hush,” Mama said instantly, her face blanching with a mixture of censure and mortification at her daughter’s blunt manner of speech.