A Cage of Roots (14 page)

Authors: Matt Griffin

At the bottom of a slope, the passage levelled out and opened into a vast cavern. Drops of water echoed as they plopped into deep pools. At the far side was a smaller opening, and from this yellow light flickered. An urge to turn and run surged through Benvy, but she resisted.

I bet they expect the girl to run. I bet Taig wished he had taken Finny or even Sean. I bet they’re just waiting for me to fail.

She walked on between the pools.

When she reached the opening, she fought one more powerful compulsion to leave as quickly as she could. She bit her lip and closed her eyes.

Come on Benvy. Show them

.

She went in.

She found herself in a large room, where the walls were hewn into pillars and alcoves. At the top, between two pots of fire, there was a boulder of marble, cut cleanly in half. Splashes of gold shimmered in the firelight on its

rough flanks. Sitting on top was a woman – at least a sort of woman. She was naked and beautiful, but her forehead was unnaturally high and two long, curved horns sprung from it in a graceful arc. Her ears were like an animal’s; a cow’s or a goat’s perhaps, falling at right angles from her head. They flicked and moved independently. Her eyes were thin and wide and yellow, with black slits for pupils. She rested one long-fingered hand on a huge harp beside her. It was made of bones.

‘Greetings, Benvy Caddock,’ she said. Her voice was sonorous and smooth. It fell on Benvy’s ears like syrup. Benvy was still afraid, but felt inexplicably a little more at ease.

‘Hello,’ Benvy responded, ‘I mean, uh, greetings.’

‘You have come for the javelin of Taig McCormac, yes?’

‘Em, yes. Yes, I have.’

This was easy, so far.

‘Good. We will get to that soon. First, let us talk.’

Benvy thought talking to this woman wouldn’t be too bad.

‘You are a heavy-set young thing, aren’t you?’

Benvy blushed, but she was not offended. It was the truth.

‘Em, yes. I guess so.’

‘But you would like to grow to be very beautiful?’

‘I don’t really care about that stuff,’ Benvy said, bashfully.

‘Don’t you? You don’t care that you are more like a boy?’

These words carried a little more sting than before.

‘I’m not …’ Benvy frowned now. The woman was right, of course, but it did hurt a little.

‘I’m sorry, child. I don’t mean to offend you. I have seen you bloom, Benvy Caddock, as a young woman. And I have seen you age like a willow, bowing down to the river over the years and drifting happily to death. This is one fate.’

Benvy listened, puzzled, and began to feel a great weariness. ‘I’m sorry. Do you mind if I sit? I’m so tired.’

‘Sit, please,’ replied the woman. She beckoned to a chair of stone immediately behind Benvy. It must have always been there, though Benvy hadn’t noticed. She sat. It was quite comfortable, for a slab of rock.

‘What do you mean, “one fate”?’ she asked.

‘I have seen the other too. The course you are on now. You are hard and strong and die like an oak, alone. Unloved.’

The woman began to pluck idly on the strings of her harp. The notes were disordered, but pleasing.

Benvy could not be sure she had heard correctly. The music coated her in warmth, caressing her. She stopped shivering. But the woman’s words gnawed at her nevertheless.

‘But that’s silly. Lots of people love me!’ she said sleepily, half to herself.

‘Your friends

fear

you. You are a bully.’

‘What? No! It’s just joshing; they know that.’ Benvy was slurring a little now.

‘Your family

resent

you, because you were born a girl.’

‘I’m tough because of my fam–’ Benvy almost nodded off, but forced herself to concentrate. ‘You try having an older brother! And parents that wish you were another son. And I’m not really ugly, am I? I could be pretty if I wanted. I …’

The woman laughed and shifted her position. Her body was so lithe and shapely. Benvy had never seen anyone as perfect – even with the features of an animal.

‘Pretty? No, dear. You are not pretty. A meadow is pretty. You are a bog.’

‘Hey!’ Benvy said, cross but drowsy. ‘That’s not … I’m not … Who the hell are you to say these things? What do you know about me?’

The woman

was

being very cruel. And yet Benvy still felt in awe of her, comfortable here in the warmth of the cave.

Maybe she’s right, in a way

.

‘I’m sorry, child, if I offend you further. It is not my intention. You seek the javelin of Taig McCormac. I would like you to have it. I am tired of guarding it. I will give it to you. First, there is a question. If you answer correctly, you can have your javelin. If your answer is wrong, you will die.’

Benvy was confused. She felt woozy. The room blurred in and out of focus while the notes trickled from the harp and swam in her head. ‘Ask it then.’ The words stumbled out of her.

‘I am the truth – I see who you really are. You are a lie. You cannot accept the truth. My question is thus: do you wish to be true?’

‘True?’ Benvy slurred. ‘What do you mean? Admit those things about my friends? My family? I … I don’t …’

Maybe I am a liar,

she thought.

Maybe this woman is right and people are afraid of me; maybe my family do resent me and I just refuse to admit it. Maybe it’s time for me to accept the real me.

‘What … I mean … I think so. I would like to be true.’

The woman grinned and ran her tongue along her teeth. They were long and sharp.

‘I thought as much, child. You seem tired. Shall I play you a song?’

Music sounded like a great idea. Benvy was

so

tired, maybe a rest would do her good. And Taig’s last words had been:

Listen to the music

.

‘Yes, please.’ She barely had the energy to form the words. Her eyelids were like lead.

The woman pulled the harp towards her and started to play with purpose. The sound was like wind in the leaves or waves on the sand. It was long grass, gurgling streams, birdsong, summer.

Benvy fought the urge to sleep, prising her eyes open with her fingers and looking blearily around her. The cavern walls seemed to writhe in time to the music, and her vision danced from thick blurriness to painful clarity. Flashes of light sparked like electric current behind her eyes, and it seemed the more she struggled, the sharper the bursts of pain. She tried to focus on the woman, willing the image to stop swaying, and battling wave upon wave of dizzy nausea, as the lights flared like fireworks just inches from her face.

For a moment she could see clearly, but it was all the more confusing, for dreams were starting to invade her waking vision. Where once the woman had been so distinctive, now she looked more than familiar. Thick, sandy hair tumbled onto strong shoulders. It framed a face that mirrored her own, but older, more graceful; more

proud

. Benvy realised it was herself, and felt a surge of hope that this was some vision of her future, until another wave of nausea took hold, and a fresh volley of lights assaulted her. It only eased when she allowed herself to slip into the warmth of the music and the heavy arms of sleep.

Benvy’s eyes closed. But deep in the fog of her drowsiness something was addling her. A doubt about the woman was coaxing her out of slumber. Nothing this creature had said felt right. Nothing about

her

seemed real or true. She resisted the queasiness, ignored the sting of dazzling lights.

The fog cleared. ‘

You’re

the lie!’ Benvy roused herself and stood from the seat.

The woman stopped playing, and let out a seething hiss.

‘You’re the lie!’ Benvy shouted again – fully alert now. ‘All of those things you’ve said have been lies! I don’t

wish

to be true: I’m Benvy Theodora Caddock. And that’s as true as it gets!’

Before her, the woman began to change. Her cheeks fell like bags of pebbles; her eyelids swelled and then shrivelled around bloodshot eyes; her skin dried and cracked like baked mud. Her back hunched and her long hair, once black and glimmering, fell to the floor, while the tufts that remained, hardened into brittle white wires. She looked ancient.

‘Go and be true to yourself then, Benvy Caddock. And have your prize.’

Propped against a nearby pillar was a javelin of red gold.

T

he inferno took the castle greedily, pulling it down into its white-hot belly, while Fergus and Sean watched from the forest, waiting for Goll. Sean had noticed a few figures escaping and running to the surrounding fields, and he worried that some may not have made it. Had anyone actually died as a result of their escape? He wasn't sure he could live with that, even though they had been more than happy to hang him. And he still could not quite believe what he had seen Goll do.

âAnd you say there are more of them â Old Ones â that can control the weather?' he asked Fergus.

âNot control as such, lad, no. They can call on it when they really need to. But yes, there are a few around,' Fergus replied. He was pinching the wound on his cheek to stem the blood flow. His beard was matted with it. In truth, he looked pretty haggard.

âAre you alright?' Sean asked.

âI'm grand. No need to ask again.'

âWhat did you say back there, to the captain I mean? Before you â¦'

âI told him he was about to die,' said Fergus. For a moment his face was daubed with sadness. âThank you for stopping me.'

Dawn was arriving, brushing the horizon with purple as the blackened stump of the Norman stronghold spewed thick smoke into the sky. Around them the forest was waking up.

âHave you killed many people?' Sean asked after a while.

âCountless,' came the short response. It shocked the boy, but he tried not to show it.

âDo you think many died in that fire?'

âOnly the ones who shouldn't have been there,' Fergus replied.

Sean didn't quite understand, but then something dawned on him: he had only seen Norman soldiers. He hadn't seen a single farmer or market trader or

normal

person. A sudden snap of a twig and a rustle of leaves behind them made him swerve. Emerging from the foliage was a throng of locals, all peasants; ten, twenty, thirty, fifty appeared through the thickets. They were all armed with whatever tools they could use to defend themselves. Goll was the last to appear.

âWell, Fergus McCormac, you always did have a knack

for turning up to the right fight at the right time!' he said jovially, clapping his hands on the giant's shoulders. âCouldn't have done it without you, big man!'

He gestured to a nearby farmer, who approached and dropped their packs nervously at their feet, then hurried back to his people. Fergus and Sean were both shocked that their bags had been recovered, and shouted thanks after the retreating figure. The backpacks were singed black, but otherwise miraculously undamaged.

âYou didn't do yourself any favours by getting locked up in the pillory, Goll!' Fergus said.

âAch, you know yourself. I can't be pulling storms down whenever I feel like it. Anyways, the main thing is we hit them hard and these good folk are free. The struggle goes on, however.'

A voice from the throng said something in that Irish-like language, asking a question aimed at Fergus.

âOh, he's real alright!' Goll laughed. âIn these parts the legend of Fergus the Mountain is very real indeed. And he'll be a great help in the struggle!'

âI'm afraid I can be of no further use, Goll,' said Fergus. âWe're only here by accident. And I hoped against hope that you might be around to help us find another gate. I thought I'd have to find a way to escape, and then search the land for you. The fact that you were there was nothing short of a miracle.'

âThe girl?' Goll asked, suddenly grave.

âAye.'

âGods help us all. You'll be needing a few more miracles so. And you're taking this young fella to the Gomor first, I'm guessing?'

âI am.'

âThen may the gods help

you

, boy.'

Goll had brought them on a long and twisty path through the outskirts of the woods, avoiding the open plains where they might be seen. After a half a day's march, they had arrived at the foot of a wide and perfectly conical hill. At its summit, six imposing boulders stood, impossibly balanced on their narrowest points, each decorated with the now-familiar spirals. They circled a small mound of grass, which held three flat stones on one side. Between the stones was a deep and silent opening.

âYour gate,' Goll said. âThis should take you to where you need to go.'

Fergus and Sean thanked him, and Goll gave them each a long hug. As Sean was held in his musty arms, the druid whispered something in that old Irish, then added, âA blessing of luck for you, Sean. I pray that it helps you. You will need all the help you can get.'

Fergus kneeled at the stones and began to hum, running his fingers along the pattern. Goll stood behind, arms raised, and joined in the droning. Clouds gathered, darkened and spilled heavy drops of rain on them to rolls of thunder. Fergus's wide finger left a trail of light behind it; the opening began to shine.

âOn you go, lad,' Fergus instructed.

They emerged beside a murmuring stream, lined with tall reeds draped in mist. Around them, thrust from the earth, were steep mountains, coated in spiky grass of brown and amber and yellow. They loomed in and out of the thick grey haze like islands out at sea. Here and there, gushing streams cut down their sides, hurling themselves over sheer drops as waterfalls.

âHave you any food left, Sean?' Fergus was rooting through his own pack to see what he had.

âI have a couple of sandwiches, although I'd say they're gone off by now. They were egg.'

âYou'll need something, anyway. Eat the bread. Take a drink from the stream. We'll need to get moving soon, and you'll need your strength.'

Fergus managed to find some big biscuits, wrapped in newspaper in the bottom of his bag. âHere, have these. An old recipe. They'll help you along.'

âWhat about you?' Sean asked, genuinely concerned.

Fergus really wasn't looking his best, and the cut on his

cheek was leaking again.

âI'll be grand. It's you that needs it. No arguments: eat. I'll fill your flask.'

Sean didn't protest any further. He took a sandwich and scraped the pungent filling out, eating the bread hungrily. He took a piece of the biscuit and ate. It was good, like a full meal in just a mouthful.

âWow, these are nice! What's in them?' he asked, spraying out bits of oat.

âProbably best you don't know. Here, drink.'

Sean took a long draft of the water. It was sensational, coursing down his throat; he could feel his body accepting it gratefully. After finishing the biscuit and taking another drink, they set off, heading up to higher ground and rounding the mountain they had emerged from. The going was tough as they climbed, picking their way through craggy rocks and slipping on the long, thick grasses. Sean felt energised by the food and water, but when Fergus suggested a break after a long march, he was hugely relieved.

From their new vantage point, the boy could see for the first time that they were close to the sea. The mountains fell down to it, their lower slopes disappearing into the metallic water at angles, forming bays and inlets where the water was calm. Further out, it boiled and thrashed, and Sean could make out the white lines of huge waves charging the coast. Ahead of them, the incline levelled out,

dipped and rose again to another peak, as if two mountains were conjoined.

âWe're not far now, lad. Just over that next hill is where you'll face your test,' Fergus said, grimly.

Sean knew there was no point in asking for any other information; he had already tried more than once. Fear squirmed again in his belly, but with false confidence he said: âFergus. So far I've been kidnapped in a forest, shown a magical vision, I lied to my mother, narrowly avoided arrest, had a crossbow aimed at my head and just managed not to get hung, instead welcoming fire and lightning just metres away from my face. Of all of those things, my mother is the most frightening. So I'm confident I can handle whatever is over that hill. And I don't know if you heard, but I'm good at tests.'

âI hope so, boy,' was all Fergus said.

When they had caught their breath and quenched their thirst, they lifted their bags onto tired shoulders and continued up the slope to where the mountain plateaued. The fog had thickened, so that they could only see a few metres around them. Ahead, the adjoining peak was a hulking grey phantom in the white. When the ground began to rise again, Fergus stopped.

âThis is where I wait, Sean,' he said. âOn the other side of this hill there is a valley. In the valley is my hammer. The hammer belonged to my father, Cormac, and it has great

power. But there is something else in that valley, Sean. There is death.'

Sean swallowed hard.

âBring it back to me, lad,' Fergus said, patting the boy's shoulder. âI believe you can.'

âNo problem!' Sean replied, his over-confidence a thin mask. He was trembling. He gave a final worried smile, turned and set off up the incline.

From the top, Sean looked down a long but gentle descent of sharp rocks and auburn grasses to a valley mostly lost in the mist. There was total silence, except for a faint clicking sound that he guessed was some kind of bird. There was no sense in dallying; he picked his way among the stones. At the bottom, his range of vision did not improve much, and his glasses began to fog up, so that several times he had to take them off and wipe them on his shirt.

He made his way slowly along the valley floor, his eyes darting around him. He was only truly aware of the extent of his fear now. He was utterly petrified. He still couldn't see a great deal, and the landscape was unchanging, so that his sense of direction was skewed despite not having turned anywhere. The haphazard click click click persisted, growing a little louder as he went.

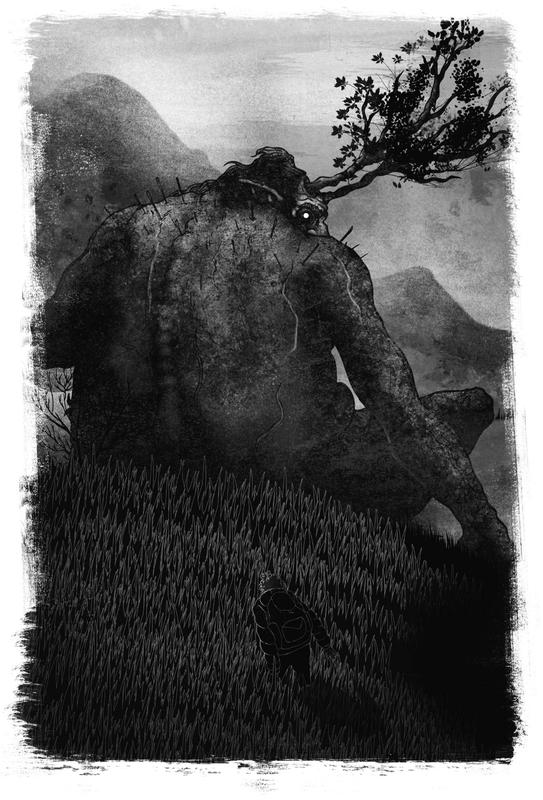

A few metres in front of him, he thought he could just make out the shadow of something in the cloud. Sean edged forward carefully, and soon there was no denying it:

something huge was in front of him and it moved, shuddering slightly. The noise was clearer now, and unmistakably coming from the spectre ahead. It was not just a click though; it was joined by something else, a kind of slobbering: squelching, snuffling, grunting. Like ⦠eating.