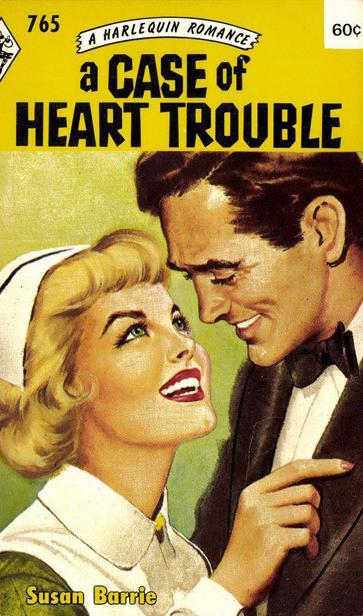

A Case of Heart Trouble

Read A Case of Heart Trouble Online

Authors: Susan Barrie

Harlequin Books were first published in 1949. The original book was entitled “The Manatee ” and was identified as Book No. 1 — since then over seventeen hundred titles have been published, each numbered in sequence.

As readers are introduced to Harlequin Romances very often they wish to obtain older titles. In the main, these books are sought by number, rather than necessarily by title or author.

To supply this demand, Harlequin prints an assortment of “old” titles every year, and these are made available to all bookselling stores via special Harlequin Jamboree displays.

As these books are exact reprints of the original Harlequin Romances, you may indeed find a few typographical errors, etc., because we apparently were not as careful in our younger days as we are now. None the less, we hope you enjoy this “old” reprint, and we apologize for any errors you may find.

OTHER

Harlequin romances by SUSAN BARRIE

904—MOON AT THE FULL 926-MOUNTAIN MAGIC 967—THE WINGS

OF THE MORNING 997—CASTLE THUNDERBIRD 1020—NO JUST CAUSE 1043—MARRY A STRANGER 1078—ROYAL PURPLE 1099—CARPET OF DREAMS 1128—THE QUIET HEART 1168—ROSE IN THE BUD 1189— ACCIDENTAL BRIDE 1221—MASTER OF MELINCOURT 1259—WILD SONATA 1311—THE MARRIAGE WHEEL 1359—RETURN TO TREMARTH 1428—NIGHT OF THE SINGING BIRDS 1526—BRIDE IN WAITING

Many of these titles are available at your local bookseller, or through the Harlequin Reader Service.

For a free catalogue listing all available Harlequin Romances, send your name and address to:

HARLEQUIN READER SERVICE,

M.P.O. Box 707, Niagara Falls, N.Y. 14302 Canadian address: Stratford, Ontario, Canada

or use order coupon at back of book.

SUSAN

BARRIE

HARLEQUIN BOOKS

First published in 1963 by Mills & Boon Limited, 50 Grafton Way, Fitzroy Square, London, England

Harlequin edition published October, 1963. Reprinted 1974

All the characters in this book have no existence outside the imagination of the Author, and have no relation whatsoever to anyone bearing the same name or names. They are not even distantly inspired by any individual known or unknown to the Author and all the incidents are pure invention.

© SUSAN BARRIE 1963 Printed in Canada

CHAPTER ONE

The light at the end of the corridor was going on and off impatiently. It meant that Dr. Martin Loring was ringing for some attention, and Nurse Drew quickened her footsteps when she realized that for the first time for days she was to be allowed to answer the summons.

Usually, either Sister Grigson herself or Nurse Barratt answered Dr. Loring’s bell. He was the white-headed boy of the nursing-home, the senior consultant who had been involved in a collision with a taxi while on his way to see one of his own patients. Ardrath House had seldom been thrown into such a state of flurry, perturbation and excitement as on the day when he had been brought in, pretty badly injured, and all the younger nurses hoped secretly in their hearts that they would be the one to “special” him.

Nurse Drew, a mere first-year pro, hadn’t, of course, stood a chance. In the early excitement, and while the ripples caused by it were spreading all over the place, she had been required to sit by him for a few hours on the first critical night, and she had done the same thing the following night. But after that she had been switched to day duty, and no one had allowed her to get near him. Anyone as insignificant as Nurse Drew could make tea for him, but she was not allowed to carry it in. She could mix him a milk drink, but—there again—she was not allowed to find out whether he drank it. Whether, perhaps, he enjoyed it.

But now—for the first time since he had begun to make real progress—she was on hand when his light started to flicker, and there was no one to put her firmly aside and say:

“All right, Nurse, I’ll attend to this!”

He was lying with his eyes fixed almost broodingly on the door when she opened it, and his whole expression registered a sort of sullen resignation to being where he was. He was not a good patient—he was probably the worst Ardath House had had for some time—but for a man who had already climbed high in his profession, and was revered not only in this country but abroad, he was astonishingly good- looking. Almost boyishly good-looking, which perhaps accounted for the feeling of surprise patients had when they saw him for the first time.

His hair was thick and dark, and it curled slightly—which was a disadvantage for a man of thirty-seven who would have preferred to be sleekheaded, with a lot of distinguished grey in his hair. His eyes were a mutinous and rather Irish grey, and his mouth was so handsome and arrogant that it shook the nurses who looked after him every time he permitted it to part slightly and provide them with a glimpse of his excellent white teeth.

Not that he did that very often—either when he was a patient, or when he was simply and solely Dr. Martin Loring, arriving in his long cream car to be welcomed by Matron. He was much more addicted to frowning—rather fiercely, at times—and when Nurse Drew entered the room he was frowning so forbiddingly that her heart sank.

“Oh, so it’s you, is it?” he said, and to her utter amazement he lay back and sighed as if in relief. “I was beginning to wonder what had happened to you. I thought perhaps you’d become so discouraged by the goings-on in this place that you’d decided to give up nursing for good and all.”

“The goings-on?” She took a seat beside the bed, and presented her demurest expression to him. Her green and white uniform suited her so much that she ought really to have worn it whenever she wanted to look her best. She had soft honey-gold hair that bent backwards deliciously under her cap, her eyes were green—unless it was the effect of the dress—her eyelashes dark, and her skin enchantingly clear for one who lived and worked in London.

“You mustn’t take words out of my mouth and repeat them,” he rebuked her, smiling at her a trifle impishly nevertheless. “Don’t you know I’m a privileged patient here?” He extended his wrist to her. “Take my pulse, Nurse. I’m sure it’s accelerated since you came into the room. It’s because you’re so pretty that they keep you out. I know nurses, I’ve worked with them for years—and some of them are hard-faced—” He broke off, before allowing the words to pass his lips, grinned, and concluded, “and some of them are angels. I’ve an idea that you belong to the angelic variety.”

Whether or not she belonged to that variety she decided that he was probably a little light-headed, and with a detached expression she took his virile wrist between her fingers and was astonished because the beats were so strong and vigorous.

He looked amused.

“Not racing like a mill stream? I’m astonished! Perhaps you ought to take my temperature.”

“I don’t think there’s any need to take your temperature, Doctor,” Dallas Drew returned with dignity ... all the dignity befitting her twenty-one years and her uniform. “From your chart I can see that it’s been normal for days. In fact, you seem to be improving steadily.”

“Good.” But the dryness of his tone caused her to regard him more closely. “That means I’ll be discharged from here very soon now, and although I’ll probably walk with a limp and two sticks for some time, and they tell me I’ve got to have a prolonged period of convalescence, at least it will be good to get out of here. I begin to feel I’m being smothered with too much attention.”

“At least that’s better than being neglected,” she remarked, with a return of the demureness that sat so well upon her.

“Is it?” He regarded her with the little frown that was never absent for long from between his dark brows. “Well, possibly you’re right . . . but I now know what it feels like to be at the receiving end of medical attention, and my sympathy is with the patient every time. I do assure you very solemnly that once I’m out of here they won’t get me back again very easily.”

She rearranged some flowers in a vase beside his bed, emptied his ash tray and performed a few other minor tasks of a similar nature, all of which seemed to irritate him, for he ordered her to come and sit down again beside his bed.

“But you rang,” she reminded him. “Did you want something?” “Nothing that I can think of,” he replied. “And if I rang it was probably as a result of sheer boredom.” He patted the chair beside the bed coaxingly. “Sit down, Nurse. You can spare a few minutes, can’t you?”

“Well . . She knew that she ought to be getting the afternoon tea-trays ready, but despite his air of arrogance there was something faintly pathetic and appealing about him just then. His face was thin, he had lost all the healthy tan he had collected on a recent holiday on the Costa Brava, and because his pyjamas were a very deep blue they made his eyes look rather more blue than grey, and a hollow blue at that. And when the shadows of his eyelashes — unusually long and feminine eyelashes—were reflected in them, it was more than an impressionable young woman in her first year as a nurse could do to deny him a few minutes of her time.

Nevertheless, she subsided a little unwilling on to the chair. He smiled as if he realized that this was an easy conquest.

“Tell me, Nurse . . . Drew?” he asked. “Is that it?”

“Yes,” she answered.

“Tell me, Nurse Drew, when they brought me in here, and I was pretty badly bashed about, and you sat beside me for two whole nights, I believe . . . did I say anything? I mean, did I babble, or anything like that?”

She shook her head.

“No, nothing. You were too deeply unconscious to talk.”

He regarded her with a mild suggestion of quizzicalness in his expression.

“Not even on the second night?”

“No.”

“Good,” he said softly, thoughtfully. He had a habit of making statements suddenly, and he made one now that took her breath away.

“When they let me out of here you’re coming with me. Did you know that?”

She looked amazed.

“But whatever for?”

He chided her gently.

“Oh, Nurse, Nurse, an interesting patient in need of the utmost care and attention for several weeks, and you say ‘Whatever for’! Why, to see that I swallow my pills at the proper times, of course, to make certain I don’t overtire myself or do anything rash ... in short, to supervise my convalescence! I’ve already spoken to Matron about you, and although she seemed surprised by my choice, she has agreed to humor me. You are to be released from all duty except the duty of looking after me for at least a month. Does the thought upset you at all?”

For she had turned deeply, almost glowingly, pink, and for a few moments she seemed bereft of speech.

“A—A month?” she said—or rather, stammered —at last.

He turned gingerly on to his side, propped himself on an elbow, and studied her with rather a curious smile.

“I see you are appalled,” he remarked. And then, taking her by surprise again: “How old are you, Nurse?”

She told him. “Twenty-one.”

He sighed, and stared upwards at the ceiling.

“Twenty-one! Then to you I must seem like an old gentleman about to be consigned to a wheelchair, in any case. But believe me, Nurse, I don’t feel like an old gentleman . . . not yet!”

His white teeth gleamed, she had the feeling for one moment that his grey-blue eyes actually caressed her.

Her heart was pounding wildly under her neat green uniform dress and immaculate white apron.

If he only knew how often—before his accident—the sight of his cream car coming to rest before the Regency portico of Ardrath House had practically deprived her of breath, how difficult she had found it to behave normally and naturally after his elegant, dark-clad figure had crossed the hall, with Matron at his elbow, and disappeared into Matron's private office, while she herself tried to remain concealed at an angle of the staircase! If only he knew how she had felt while she sat beside him those two nights while he was so deeply unconscious!

If only he knew how thankful she was that he was now on the road to complete recovery!

She put a hand to her little round collar, as if it were suddenly too tight and constricting, and he watched her. He asked, quietly:

“Any real objections, Nurse?”

“Of course not,” she answered.

“You won't miss the bright lights of London? I live in a very lonely place, you know ... an isolated house on the Yorkshire moors. How does that appeal to you?”

“Tre-tremendously,” she said, and wished she dared ask him what part his wife was going to play in making his convalescence a bearable interlude. For everyone insisted that he had one, although she had never once been to visit him in the nursing home.

His small daughter, yes . . . she had been brought from her school. But not his wife.

The smile that was still clinging faintly to his lips vanished.

“In case you're wondering about the other occupants of my house, you won't be shut up there alone with me. I've an old aunt who acts as my housekeeper, and an adequate staff. I promise you that you won't have anything to do but stand about with your stopwatch, and feed me grapes—and medicine, of course!”

She felt as if the breath eased suddenly in her throat, and her green eyes started to glow. He couldn't possibly mistake the glow . .