A Cold Day for Murder

Read A Cold Day for Murder Online

Authors: Dana Stabenow

Tags: #Alaskan Park - Family - Missing Men - Murder - Pub

Contents

Contents- Dedication

- Introduction

- Illustrations

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Excerpt:

A Fatal Thaw - Author’s Bio

For Don Stabenow,

my very own personal air taxi service

and pyrotechnical adviser

The phone rang on February 1, 1994. “Dana!” my editor cried. “You’ve been nominated for an Edgar!”

“Great!” I said. “What’s an Edgar?”

There was a moment of silence, followed by a spluttering explanation. The Edgar Awards were to crime fiction what the Academy Awards were to film. Then a tentative, “You know what an Academy Award is, don’t you?”

They were also, my editor said, flying me to New York City for the Edgar awards ceremony. When I finally figured out I had to dress up for it, I nearly said I couldn’t go. For one thing, I was broke, and for another, I don’t do dress-up. Not unless it’s at gunpoint.

Which this pretty much was, so I went down to Nordstrom in Anchorage and found a pair of dress slacks with pockets (very important) on the sale rack. A top to match was much harder, and by the final week before Departure Day I was starting to panic.

I finally found a dress on some sale rack that fit my budget (seventy percent off) and looked marginally okay. I took it home and cut it off to just below waist length. I went to J.C. Penny’s and found a couple of fake gold chains and hemmed them inside the bottom of what was now a top. (Sometimes I really shouldn’t read. This time the culprit was a bio of Coco Chanel, which informed me that she used metal chains to make her famous jackets hang just right. Well, what the hell, if it worked for Chanel...)

I think my black flats were from Payless ($10), and I found a pair of flashy rhinestone earrings and a couple of flashier rhinestone brooches in a junk shop. I was ready.

So the following week there I was, in the Edgar hotel in a corner room with a view all the way to Ohio. My best friend Kathy abandoned her husband and family to support me. The afternoon of the awards ceremony was sunny and warm and she said, “Statue of Liberty?”

“Statue of Liberty,” I said, and we grabbed a cab to Battery Park and a ferry to Liberty Island. We wandered around in the footsteps of our ancestors until about four o’clock, when we boarded a very full, very slow ferry back to Manhattan over oily flat seas, the saucy tang of diesel very much in the air. People were sick over the side. I was not one of them, barely.

Back at Battery Park, we discovered much to our dismay that, A, four o’clock was also the time that nearby Wall Street shut down, so cabs were very thin on the ground, and B, it was shift change for what cabs there were and they weren’t taking fares that didn’t point them towards home anyway.

Neither of us spoke subway at the time, so we waved down cab after cab, only to have them say “Nahhh” when we told them where we were going. I started to think that if we ever did get a cab I should just head for the airport, because my publisher was footing what had to be a pretty spectacular bill and they were going to hurt me pretty badly when I didn’t show up at the awards ceremony to graciously lose in person.

Finally, in an action that demonstrates precisely why she will forever be my best friend, Kathy leaped in front of a cab going the average New York City speed limit of 103MPH and forced it to a literally screeching halt. She marched around to the driver’s side and said, “You WILL take us to our hotel.”

He was so scared of her he did.

My first mandatory appearance was at a 5:30pm cocktail party. We came out of the elevator on our floor at fifteen minutes after five, undressing as we ran toward our room. We didn’t even have time for showers, so I did a quick swipe with a wet washcloth and threw on my clothes and back to the elevator we went.

We walked into the reception. Everyone there was dressed like they had just wandered off the set of Dynasty. I’d never seen so many tuxes in one room in my life.

The one distinct memory I have of that evening lends to the general feeling of unreality I was experiencing. Donald Westlake was the grandmaster that year, and he called us his tribe. He said it twice, and thumped the podium, to make sure we got it. All the writers in the room were his, Donald Westlake’s, tribe. Up until then little Dana Stabenow from Seldovia, Alaska had been a clan of one, and suddenly, I had family. Starting with the progenitor of Dortmunder.

And then they called my name. From. Up. There.

By that point I wasn’t really in my body, but, sunburned, still a little sweaty, still a little seasick, clad in cut-off dress and rhinestones, I wobbled up on stage and grasped in a shaky hand an award the existence of which I had been completely unaware only three months before.

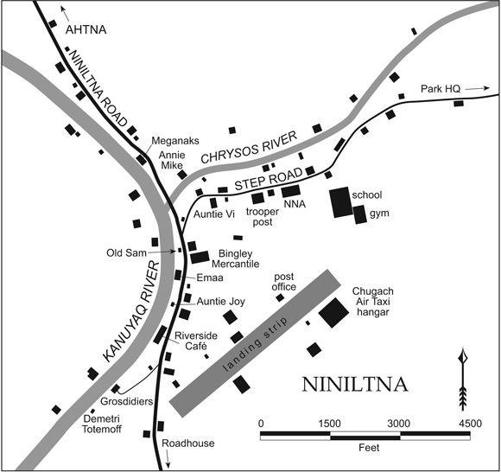

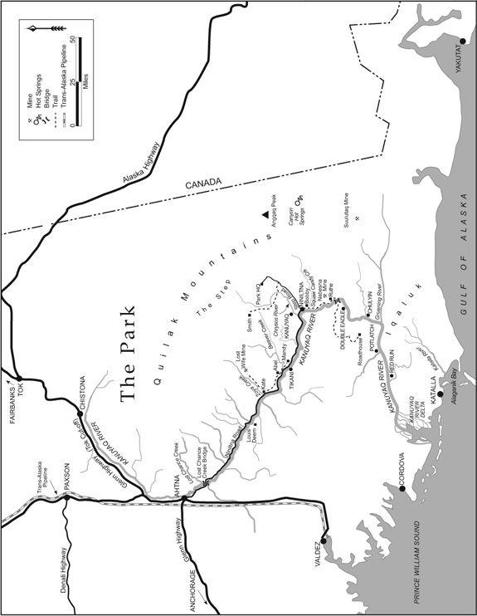

Maps by Dr. Cherie Northon,

www.mapmakers.com

.

They came out of the south late that morning on a black-and-silver Ski-doo LT. The driver had thick eyebrows and a thicker beard and a lush fur ruff around his hood, all rimmed with frost from the moisture of his breath. He was a big man, made larger by parka, down bib overalls, fur mukluks and thick fur gauntlets. His teeth were bared in a grin that was half-snarl. He looked like John Wayne ready to run the claim jumpers off his gold mine on that old White Mountain just a little southeast of Nome, if John Wayne had been outfitted by Eddie Bauer.

The man sitting behind him and clinging desperately to his seat was half his size and had no ruff around the edge of his hood. His face was a fragile layer of frost over skin drained a pasty white. He wore a down snowsuit at least three sizes too big for him, the bottoms of the legs coming down over his wingtip shoes. He wasn’t smiling at all. He looked like Sam McGee from Tennessee before he was stuffed into the furnace of the

Alice May.

The rending, tearing noise of the snow machine’s engine echoed across the landscape and affronted the arctic peace of that December day. It startled a moose stripping the bark from a stand of spindly birches. It sent a beaver back into her den in a swift-running stream. It woke a bald eagle roosting in the top of a spruce, causing him to glare down on the two men with malevolent eyes. The sky was of that crystal clarity that comes only to lands of the far north in winter; light, translucent, wanting cloud and color. Only the first blush of sunrise outlined the jagged peaks of mountains to the east, though it was well past nine in the morning. The snow was layered in graceful white curves beneath the alder and spruce and cottonwood, all the trees except for the spruce spare and leafless, though even the green spines of the spruce seemed faded to black this morning.

“I gotta take a leak,” the man in back yelled in the driver’s ear.

“You don’t want to step off into the snow anywhere near here,” the driver roared over the noise of the machine.

“Why not?” the passenger yelled back. A thin shard of ice cracked and slid from his cheek.

“It’s deeper than it looks, probably over your head. You could founder here and never come up for air. Just hang on. It’s not far now.”

The machine lurched and skidded around a clump of trees, and the passenger held on and muttered to himself through clenched teeth. The big man’s grin broadened.

Without warning they burst into a clearing. The big man reduced speed so abruptly that his passenger was thrown forward. When he hauled himself upright again and looked around, his first impression of the winter scene laid out before him was that it was just too immaculate, too orderly, too perfect to exist in a world of flawed, disorderly and imperfect men.

The log cabin in the clearing sat on the edge of a bluff that fell a hundred feet to the half-frozen Kanuyaq River below. Beyond the far bank of the river the land rose swiftly into the sharp peaks of the Quilak Mountains. The cabin, looking more as if it had grown there naturally rather than been built by human hands, stood at the center of a small semicircle of buildings. At the left and slightly to the back there was an outhouse, tall, spare and functional. Several depressions in the snow around it indicated it had been moved more than once, which gave the man on the snow machine some idea of how long the homestead had been there. Next was a combined garage and shop, through the open door of which could be seen a snow machine, a small truck and assorted related gear. He found the sight of these indubitably twentieth-century products infinitely reassuring. Next to the cabin stood an elevated stand for a dozen fifty-five-gallon barrels of Chevron diesel fuel, stacked on their sides. Immediately to the right of the cabin was a greenhouse, its Visqueen panels opaque with frost. Next to it and completing the semicircle stood a cache elevated some ten feet in the air on peeled log stilts, with a narrow ladder leading to its single door.