A Companion to the History of the Book (14 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

The tablet format’s functional dichotomy between memorization and recall is corroborated by the fact that the long extracts on Type I, reverse Type II, and Prism tablets are almost invariably from the first half or third of an elementary exercise, whereas the short extracts on Type II obverses and tablet Types III and IV are randomly distributed across the beginnings, middles, and ends of those exercises. Looking at the textual stability of the compositions, there is much more consensus between manuscripts attesting the start of a composition than those from the end. The situation is slightly complicated, however, by the fact that there is not an even preservation of tablet types in House F. Type I Ita blets account for fully two-thirds of the 366 elementary tablets with identifiable formats, perhaps because they were ideally suited to reuse as building materials (the circumstances in which they were found). Two-thirds of the 50 Type III tablets identified are multiplication tables, whereas half of the 70 Type Is and Prisms are either exercises in the more abstruse aspects of cuneiform or model legal contracts. There are only five Type IV tablets among the 500 elementary tablets in House F.

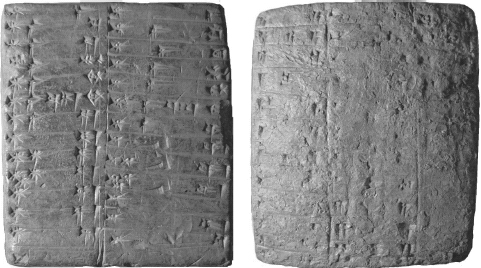

Figure 5.2

A Type II tablet from House F, showing the teacher’s and student’s copies of a school exercise on the obverse and the student’s recall of a longer passage on the reverse (3N-T 393 = UM 55-21-318). Reproduced by kind permission of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

A further 500 tablets, the other half of the surviving school corpus from House F, contain works of Sumerian literature, or extracts from them (Black et al. 2004). About 80 different compositions are attested in the house, including epic stories of legendary heroes like Gilgamesh and Lugalbanda, myths about gods and their deeds, hymns to gods, kings, and temples, debates, dialogues, and humorous stories about scribal students. What were once thought of as ancient genre designations at the end of some literary works should probably be understood rather as indicators of performance style, at least in those cases where the labels are susceptible to translation. The physical typology of Sumerian literary tablets is still under-researched, but other kinds of evidence reveal how they were created and used. Extracts were not copied from a model on the same tablet as the elementary exercises were, and neither has direct copying from one tablet to another ever been proved. While there is often a lot of agreement between individual manuscripts, variation at the level of spelling, grammar, synonyms, line order, and even compositional length and structure are also well attested and point again to memorization within a fairly fluid oral tradition (Michalowski 1992).

On the other hand, catalogues of incipits, or first lines, and large tablets containing several literary works demonstrate that compositions could be grouped into more or less fixed sequences. Some of those sequences are clearly curricular: a group of ten literary works, now known as the Decad, is found at the start of several ancient catalogues from Nippur and other cities (Tinney 1999). In House F, whereas there was one or at most two copies of most literary works, there were typically twenty copies of each Decad composition. The Decad crosses modern generic boundaries – it includes hymns, myths, and humorous works – whereas other apparently curricular groupings are primarily thematic. Its widespread distribution also points to a shared pedagogical culture within southern Mesopotamia, with remarkable textual stability across time and space. The Decad is highly unusual in its coherence and stability, however: ancient catalogues and shelf lists point to locally meaningful thematic groupings of literary works but little wider curricular standardization.

There are still many unsolved – and unasked – questions about schooling in House F. Yet it is clear that the primary pedagogical tactics were copying and memorization in the form of piecemeal rote learning. There were no textbooks to copy from, but rather scribal teachers wrote out lessons from memory, according to the needs of the students, and often moved them on to new tasks before they had fully mastered and memorized their current exercises. Nor were the trainee scribes themselves creating books but writing in order to memorize an oral tradition of knowledge, which could be very fluid, at the same time as learning to be literate for more mundane purposes. Both elementary and literary tablets, despite their overwhelmingly non-utilitarian content, functioned to train future scribes for their administrative careers (Wilcke 2000). There is no early Mesopotamian evidence of reading for pleasure, or even creating or using tablets as reference works: the intellectual tradition was almost entirely composed of knowledge internalized through repeated copying, recitation, and memorization.

Books as Cultural Capital in Iron Age Assyria

The second case study comes from a much grander setting than a humble scribal school, over a thousand years after the demise of House F. In the early first millennium bc, the political heart of the Middle East was the city of Nineveh, on the opposite bank of the Tigris to modern-day Mosul in northern Iraq. The Assyrian kings had made their capital here in c.700 bc, on a settlement founded millennia earlier. It was strategically placed for easy riverine and overland access to a vast empire, stretching east into the Zagros Mountains of Iran, west to the Mediterranean coast and Egypt, and south to the Babylonian shores of the Gulf. The Assyrian empire depended on the annual extraction of tribute and taxation, as well as the regular influx of labor from the peripheries to the center, in order to develop and maintain a sophisticated complex of palaces and temples in which the daily ceremonial of empire was performed and its ideological support system upheld.

The magnificently monumental edifices of Nineveh were amongst the first Assyrian remains to be discovered by European scholars in the mid-nineteenth century, decades before the development of professional stratigraphic archaeology. Thus the 28,000-odd tablets found in the royal citadel of Nineveh, which are now housed in the British Museum, rarely have good archaeological context (although modern museum curators have gleaned much useful data from their Victorian predecessors’ documentation and correspondence). Collectively, the Nineveh tablets are rather loosely known as Ashur-banipal’s Library, after the monarch who ruled Nineveh in 668–c.630 bc and who had his mark of ownership inscribed on many of them (Lieberman 1990). Apart from letters, administrative documents, and legal records, the palace complex contained literary and historical works, religious rituals and prayers, medical collections, and long compilations of terrestrial and celestial omens, with complex commentaries on them.

The Assyrian kings surrounded themselves with large retinues of military, political, and scholarly advisers. The scholars’ ultimate function was to guide the monarch’s political decision-making according to divine will. An “inner circle” of about a dozen highly educated men posed strategic questions to the gods and interpreted their answers through divination, by close inspection of events in the skies and on the earth. They relayed their findings and advice in letters and reports to the king, often supporting their conclusions with citations from the scholarly collections housed in the royal library. The letters themselves, many hundreds of which survive, are in Assyrian dialect, while the scholarly quotations are invariably in Babylonian.

The scholarly library tablets of Nineveh have much greater claim to be considered as books than the schoolboys’ writings of House F. They show unequivocal evidence for several levels of textual standardization, from spellings up to the categorization of texts into generic corpora associated with named scholarly disciplines (Rochberg-Halton 1984). For the Assyrian scholars, the textual stability of the literate tradition was enmeshed with the theological hermeneutics of cuneiform writing. Such works were considered to be the writings of gods or divinely inspired sages, with multiple layers of meanings embedded within the multiple possible interpretations of every sign and word. The scholars explicated this multivalency, and also collected textual and oral variants, in learned commentaries of various kinds.

Because very long compositions – collections of omens, for instance, or ritual series and their incantations – could not fit on a single tablet, they were divided into standard tabletsized chapters. Colophons on the tablets themselves recorded their place in the sequence and the first line of the next tablet, while separate indices of long works and their subdivisions were another means of managing multi-tablet compositions. Colophons explicitly state that tablets were “written, copied, and checked” from older originals, both tablets and writing boards (

figure 5.3

). Colophons and the evidence of library records reveal two types of tablet production and acquisition: writing and inheritance by indigenous scholars who were members of prestigious courtly families close to the king; and the forced transfer of both tablets and scholars from Babylonia.

Figure 5.3

Scribes using writing boards and parchment depicted on a bas-relief from the royal palace of Nineveh. Reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Ashurbanipal was one of the few Assyrian kings to have been trained in the scribal arts – by one Balasî, a senior royal scholar. He systematically built up the palace library holdings through a variety of means, as attested, for instance, on the colophons of tablets from the great

Epic of Gilgamesh

found at Nineveh (George 2003). The oldest set of

Gilgamesh

tablets in the library was probably written several hundred years earlier; another was perhaps written for his grandfather Sennacherib and only later inscribed with Ashurbanipal’s mark of ownership. A third set had belonged to the famous scholar Nabû-zuqup-kena, the grandfather of Ashurbanipal’s senior scribe. The colophons of a fourth set claim them to be in Ashurbanipal’s own hand, as do copies of many other scholarly works (

figure 5.4

). None of these four sets comprises the full sequence of twelve tablets that made up the

Epic

; it is unclear whether this is a consequence of partial preservation and recovery or reflects actual patterns of ownership.

The Assyrian

Gilgamesh

was a much longer and more standardized composition than the Sumerian literary works attested in schools like House F a thousand years earlier. Tradition had it that a Babylonian scholar by the name of Sîn-leqi-unninni had crafted the new work from various different sources some time in the late second millennium bc. While a confident editorial hand is clearly discernible in the new

Epic

, almost no manuscript sources survive from the 500-year period during which the transformation was supposedly wrought that might allow further insight into the process.

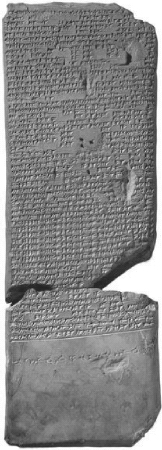

Figure 5.4

A tablet from Nineveh recording the myth of the goddess Ishtar’s descent to the Underworld. The colophon at the bottom reads: “Palace of Ashurbanipal, great king, king of the land of Ashur.” Reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Forced acquisition of cultural products had been an important part of the Assyrian strategy for the subjugation of Babylonia throughout the eighth and seventh centuries bc, but was particularly favored by Ashurbanipal (Frame and George 2005). Three long letters, known only from Babylonian apprentices’ copies of several hundred years later, suggest that he ordered the temples of Babylonia to make copies of all scholarly works in their possession to send to Nineveh. One letter, supposedly from Ashurbanipal himself, commands the recipient to go to Borsippa near Babylon to “search out for me” a long list of named works, “and any texts that might be needed in the palace, as many as there are, and also rare tablets that are known to you but do not exist in Assyria, and send them to me.” The other two purport to be responses from Babylonian scholars to a royal command for copies of similar material. They both quote the king’s command directly, and are at pains to portray themselves as obediently responsive.