A Companion to the History of the Book (20 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

Already in the Song dynasty, unauthorized editions were a problem, and attempts at employing a form of copyright to protect commercial publishers failed. Even official government editions published in the capital Hangzhou were reprinted without reprisal in the provinces. Book pirates were so bold as to copy printers’ colophons and cover pages, including copyright warnings, so that buyers had no suspicion that they were acquiring a spurious edition. In the late Ming, the custom of printing veiled threats on the cover page (for example,

fanke bijiu

, “unauthorized reprints will be investigated”) was widespread but utterly ineffectual. By then, with a highly stimulated economy, an increased demand for books, and a highly diversified publishing industry, book piracy had become endemic.

Commercially printed books in China have a long history, but because of different conditions they developed quite differently from the West. Earlier restrictions and a partial government monopoly over aspects of printing in the eleventh century did little more than impede its rate of growth, and by the next century the commercial implications of printing were full blown. More than twenty commercial publishers and booksellers are known to have been active in Hangzhou, the Southern Song capital, during much of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Classical, philosophical, religious, literary, educational, and geopolitical texts were sold to Japan, Korea, and other neighboring states throughout the Song. Attempts by Chinese authorities to control exports for political reasons failed to halt the flow of books: the smuggling was motivated by profit and seldom by politics (Tsien 1985; Zhang 1989).

From the twelfth century on, book collections began to show evidence of the impact of printing. For example, the private collection of about 1,500 titles of Chao Gongwu (d. 1171) contained both manuscript and printed editions. Chao’s

Junzhai dushuzhi

(Bibliography of the Junzhai Collection), published shortly after his death, is the oldest extant descriptive catalogue in China: its printed edition of 1250 survives. As the Southern Song economy flourished and printed books became more plentiful, their prices decreased and their circulation increased. Nowhere was the impact more pronounced than in education, as reflected in the number of civil service examination candidates, which steadily swelled throughout the Song period (Zhang 1989).

Private book collections grew in the Yuan dynasty, and, after a period of economic depression in the first part of the Ming, they continued to expand. The Tianyige library in Ningbo, founded in 1561 by Fan Qin (1506–85) after a successful career as a government official, is the oldest existing private library in China. Fan not only collected books and passed them on to later generations, he also published several useful works. Tianyige was the acknowledged inspiration for the design of the seven libraries built to house the Qianlong emperor’s

Siku quanshu

collections. Although the original Tian-yige book collections have become depleted by calamity and attrition, they and their catalogues provide important material for the study of Ming libraries. Large book collections were also amassed by Ming booksellers and publishers, notably Mao Jin (1599–1659) of Changshu in Jiangsu province. Jiguge was the name of his personal library as well as the most common hallmark for his commercial publications. The fact that, in this period, old books and manuscripts were increasingly being collected as artifacts greatly contributed to their preservation.

The growth of publishing activity in the late Ming led to the introduction of many new genres, especially those containing woodcut illustrations, as well as new methods of printing, such as polychrome printing (

caise taoyin

), which began by applying several colors to a single woodblock and developed into the “assembled-blocks” (

douban

) method, which uses separate woodblocks for different colors. The 1626 polychrome publication of

Luoxuan biangu jianpu

(Models of Letter Paper of the Wisteria Studio) by Wu Faxiang (b. 1578) in Nanjing apparently was the first to incorporate the

gonghua

technique, a form of blind printing in which subtle images are embossed on some blank pages. Hu Zhengyan (1582–1672) published

Shizhuzhai shuhuapu

(Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Calligraphy and Painting) as a set sometime between 1633 and 1644, although parts may have been published as early as 1627, and

Shizhuzhai jianpu

(Models of Letter Paper of the Ten Bamboo Studio) in 1644. Both were published in Nanjing and printed in six or more colors, and the latter was the first to cite the

douban

technique. Two-color textual printing (

zhumo taoyin

) began in the Yuan, but it was first widely practiced by the Min and Ling lineages of Huzhou in the first decades of the seventeenth century. They also produced several editions with as many as four colors for commentaries in addition to the main text printed in black.

Private individuals, schools, governmental and religious institutions, as well as commercial publishers all contributed to the flourishing book culture in the Jiangnan region in the south of China at the time. In addition to standard texts, publications in demand included guidebooks to examinations, popular fiction, literary collections, local gazetteers, travel books, household encyclopedias, and reprint collections. The bookshops of Nanjing, Suzhou, and Hangzhou were renowned, as were the block-cutters of Huizhou. Book illustration prospered as never before, led by the Huizhou School and followed by other regional styles. The mobility of civil servants and of the literati class in general, as well as the itinerant nature of workers in the publishing industry (for example, editors and block-cutters), militated against narrow provincialism. Wang Tingna (1567–1612), for example, was a prominent Huizhou publisher who was active in the intellectual life of Nanjing.

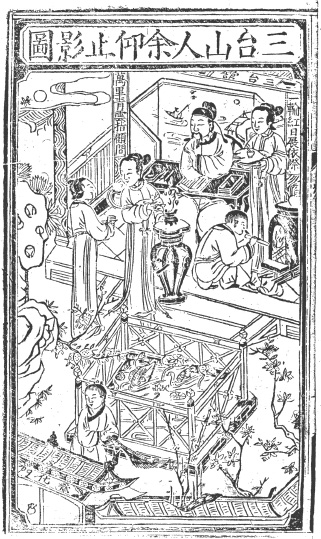

Even the important commercial publishing center of Jianyang in Fujian province further south had close ties with Jiangnan. There is evidence of collaboration among publishers and booksellers in both places and even reports of the transfer of woodblocks for printing. Yu Xiangdou (c.1560–1637) was typical of successful publishers in Jian-yang. Although unsuccessful as a candidate for civil service examinations, he seems to have considered himself better educated and a cut above many of his peers. In some of his publications, Yu takes the liberty of writing prefaces and adding textual commentaries. He also lists himself as editor or co-author of several works, and in a few he includes a woodcut portrait of himself assuming the role of a scholar (

figure 7.3

; Chia 2002).

Figure 7.3

Woodcut scene depicting the late Ming commercial publisher Yu Xiangdou. From

Shilin zhengzong

(Compendium of Literary Commentary), published by Yu in Jianyang in 1600. Private collection. Reproduced with permission.

Recognition of this surge of publishing activity beginning in the late sixteenth century has led to a scholarly debate about the “ascendance of the imprint.” Did true print culture begin as early as late Song or as late as the end of Ming? The question posed is whether the Ming dynasty was the time when imprints finally dominated book culture and significantly outnumbered manuscript texts (McDermott 2005).

Xylographic publishing in the Qing period continued to expand, albeit without the flamboyance of late-Ming publications. Certain features of Chinese books, such as the use of thread binding and the inclusion of cover pages, became firmly established in the Qing. The cover page (

fengmianye

) can be traced back to the late Song or early Yuan period. Although it resembles a Western title page, the cover page was created for commercial advertising. In addition to the title of the book and the author’s name, both usually expressed fancifully, it often included the publisher’s name and the place and date of publication. Sometimes it reported forthcoming or recently published titles as well as the price. Use of the cover page became so widespread in the Qing that even noncommercial publications contained a simplified form of it. There is evidence that the cover page derived from the printer’s colophon, in which respect it is also similar to the Western title page (Edgren 2004).

It has been suggested that the chief factor responsible for the failure of the traditional Chinese publishing industry to develop along Western lines was the absence of capitalism. Conditions began to change only after Japanese and Western merchants introduced lithography and Western lead type and printing presses into China, through Shanghai, in the late nineteenth century. The long history of traditional print culture in China and favorable conditions in Shanghai resulted in a unique response to the newly introduced technology (Reed 2004). Superficially, books gradually came to resemble their Western counterparts in the twentieth century. Western binding techniques and decorative styles were introduced, machine-made paper from wood pulp replaced traditional paper stock, and text began to be set horizontally rather than vertically. Due to historical circumstances and the particular characteristics of its language and script, the evolution of modern Chinese typography has followed an unusual course (Heijdra 2004b).

The most important modern Chinese publishers of the first half of the twentieth century were

Shangwu yinshuguan

(Commercial Press Ltd.), founded in 1897, and

Zhonghua shuju

(Chung Hwa Book Co.), founded in 1912, both located in Shanghai. Other influential publishers included

Kaiming shudian

(Kai Ming Book Co.) and

Shijie shuju

(World Book Co.), also of Shanghai. All kinds of publishing enterprises emerged in China during the turbulent decades before the end of the Second World War. After 1949, the major publishing houses were reorganized within China, and factious groups established new businesses under their old names on Taiwan. Newly founded publishers, such as

Wenwu chubanshe

(Cultural Relics Press) in Beijing,

Shanghai guji chubanshe

(Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House) in Shanghai, and

Yiwen yinshuguan

(Yee Wen Book Co.) on Taiwan, appealed to the educated class of Chinese. University presses and specialty publishers were established to serve various segments of society.

The institution of public libraries, university libraries, and national libraries in the twentieth century in China has profoundly affected the availability of bibliographical resources. Leading libraries include the National Library of China (Beijing), the Peking University Library (Beijing), the National Central Library (Taiwan), and the Shanghai Library (Shanghai). Libraries have lately promoted automated cataloguing of books and digitization of texts.

By the end of the twentieth century, new electronic possibilities, especially for publishers, had leveled the proverbial playing field. The formerly clumsy hand-setting of Chinese characters from vast founts of type has been eliminated. Chinese text can now be entered by keyboard as efficiently as any other script in the world, while traditional reprints can be produced directly by “optical character recognition” scanning.

References and Further Reading

Brokaw, Cynthia (1996) “Commercial Publishing in Late Imperial China: The Zou and Ma Family Businesses of Sibao, Fujian.”

Late Imperial China

, 17 (1): 49–92.

— (2005) “On the History of the Book in China.” In Cynthia Brokaw and Kai-wing Chow (eds.),

Printing and Book Culture in Late Imperial China

, pp. 3–54. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Carter, Thomas (1955)

The Invention of Printing in China and its Spread Westward

, revised by L. Carrington Goodrich. New York: Ronald Press.

Chia, Lucile (2002)

Printing for Profit: The Commercial Publishers of Jianyang, Fujian (11th–17th Centuries)

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center.

Chow, Kai-wing (2004)

Publishing, Culture, and Power in Early Modern China

. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Drège, Jean-Pierre (1991)

Les Bibliothèques en Chine au temps des manuscrits (jusqu’au Xe siècle)

[Libraries in China in the Age of Manuscripts to the Tenth Century]. Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient.

Edgren, Sören (2004) “The

Fengmianye

(Cover Page) as a Source for Chinese Publishing History.” In Akira Isobe (ed.),

Studies of Publishing Culture in East Asia

, pp. 261–7. Tokyo: Nigensha.

Heijdra, Martin (2004a) “Technology, Culture and Economics: Movable Type versus Woodblock Printing in East Asia.” In Akira Isobe (ed.),

Studies of Publishing Culture in East Asia

, pp. 223–40. Tokyo: Nigensha.

— (2004b) “The Development of Modern Typography in East Asia, 1850–2000.”

East Asian Library Journal

, 11 (2): 100–68.

Helliwell, David (1998) “The Repair and Binding of Old Chinese Books.”

East Asian Library Journal

, 8 (1): 27–149.

Inoue, Susumu (2002)

Chūgoku shuppan bunka-shi

[Cultural History of Chinese Publishing]. Nagoya: Nagoya daigaku shuppankai.

McDermott, Joseph (2005) “The Ascendance of the Imprint in China.” In Cynthia Brokaw and Kai-wing Chow (eds.),

Printing and Book Culture in Late Imperial China

, pp. 55–104. Berkeley: University of California Press.