A Fortunate Man (4 page)

Authors: John Berger

âDoctor, can a woman of my age have heart trouble?'

âIt's possible. Did you ever have rheumatic fever when you were a child?'

âI don't think so. But I get so out of breath. And if I bend down to pick something up, I can scarcely stand up proper again.'

âLet me have a listen. Just pull up your blouse.'

She wore a very worn black lace petticoat. The room was as little furnished as the kitchen. There was a large bed in one corner with some blankets on it and some more blankets on the floor. There was also a chest of drawers with a clock on it and a transistor radio. The windows were overgrown with thick ivy and since there was no plaster ceiling and holes in the rafters, the room scarcely seemed geometric and was more like a hide in a wood.

âWe'll examine you properly when you come up to the surgery but I can promise you now that you haven't got a serious heart disease.'

âOh I'm so relieved.'

âYou can't go on like this. You know that don't you? We've got to get you out of here â'

âThere's lots more unfortunate than us,' she said.

The doctor laughed, and then so did she. She was still young enough for her face to change totally with her expression. Her face looked capable of surprise again.

âIf I won the football pools,' she said, âI'd buy a big house and start a big home for children, but they say they make all kinds of difficulties these days for that kind of thing.'

âWhere were you living before you came here?'

âIn Cornwall. It was lovely there by the sea. Look.'

She opened the top drawer of the chest and from among her own stockings and children's socks she took out a photograph. It showed herself in high-heeled shoes, a tight skirt and a chiffon scarf round her head with a man and a small child walking along a beach.

âThat's your husband?'

âNo, that's not Jack, that's Cliff and Stephen.'

The doctor nodded, surprised.

âI'll say that for Jack,' she continued, âhe never makes no distinction between the kids that are his and those that are mine like. We share fifty-fifty. He's better to Steve than his own father. It's just that he can't touch me.'

She looked at the photograph, holding it out at arm's length.

The doctor asked whether she and her husband wanted to stay in the area and what would they think if he tried to get them a Council house. She answered without glancing away from the photo.

âYou have to ask Jack about that. We do everything fifty-fifty.'

Still holding the photograph she let her arm fall on to her lap and looked at the doctor, her eyes now angry.

âCan you tell me if I'm too old? Jack says I'm too old. I only want it every two or three months.'

âThat's all to do with your being tired and feeling you can't cope.'

âI've had a bellyful all right. Sometimes I think I just can't go on. I just want to lie down and stop.'

She got up and put the photograph back in the drawer. âDo you like music?' she said and switched the radio on. Then after a few bars, she switched it off. She stood there against the chest, a quite different expression on her face: as though switching the radio on and off had reminded her of something.

âIt just doesn't mean anything to me. It doesn't touch me. When he makes love to me it's like a wet rag across my face. I know what real love is like you see. With the father of Stephen, when I got Stephen it was beautiful. We came together and I was able to come to him with all of me. I know what they mean when they say it is the most wonderful thing in the world, it was like that when I got Stephen because I could come to him and he wanted me like that. And I shall never forget it â I lie awake and think of it yet â because it has never been like that again when it was like heaven when I got Stephen.'

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

We fell in love with it ten years ago â for the view. And I must say we've never regretted it, not even in the winter. It's so peaceful. Do you know last spring when I was walking along the path from the village I saw something standing in the front gate. I could see it as I turned the corner by the wood. It looked like a dog but it didn't, if you know what I mean. And do you know what it was? It was a badger. It just stood there between the gate-posts and stared at me. I didn't know what to do. Can they be dangerous? I just didn't know. Hugh was playing golf and so I went to ask Mr Hornby, and he came back with me, but by that time it had gone. But that isn't the end of the story. The badger has come to stay I think. He's invited himself. You remember the deep snow we had last winter, I don't know what we'd have done then without Mr Hornby, he cleared the path through the wood, otherwise you just couldn't get through, it was up to my waist, and it was very cold too, the cold was cruel, anyway as I was saying in the night I used to hear something on the roof, something moving about, I woke up Hugh several times and he said it was the snow shifting but I knew it wasn't because it was too cold you see for the snow to be moving, and in the morning I went to look and do you know there were his footsteps in the snow on the roof, would you believe it?

I suppose he was so cold up there in the wood behind that he came down in the dark for a bit of warmth. He could have nestled up against the chimney â Hugh says not, but I'm sure he could â and got nice and warm. I often think of him up there when I'm sitting by the fire thinking. Of course it's silly but you can see what I mean about it being very peaceful, can't you? I mean you wouldn't get badgers in Birmingham where we used to live when Hugh was still at work â¦' she continues endlessly.

When she phones it is usually about him rather than herself.

âI'm worried about him, doctor, he's got a pain in his back and I think it might be a slipped disk. It all came on in that wet spell last week when he insisted upon digging the vegetable garden, the first chance for two months, he said, and now he can't straighten up.'

Sometimes it sounds more serious.

âHe's been in bed for three days and he has great difficulty in breathing. When he breathes at night â and I simply can't get to sleep listening to him â I keep on thinking he's talking, his breathing sounds like words, doctor.'

She is there at the door waiting.

âI'm so glad you've come. His whole body is collapsing. I better let you talk to him yourself, because he won't tell me what he's complaining of, he won't come out with it, he's funny like that you know, he just says all his organs are going. Which? I say. What do you mean? But he won't tell me, he just says all his organs.'

The husband, aged seventy-three, explains that he can't hold his water and that he has some pain in the lower part of the abdomen. The doctor checks his chest and stomach. He does a rectal examination to feel the prostate and to discover whether any growth is pressing on the bladder. He tests the urine for sugar and albumen. The sugar is just problematic. He diagnoses a mild urinary infection.

Thirty-six hours later she phones.

âHe just can't take any liquid at all now. He can't drink. He hasn't taken a drop since yesterday breakfast. And he keeps on falling asleep. Right in the middle of my talking to him he just falls off â I don't know what to do. He just can't keep awake, not even when I'm talking to him, he just falls asleep and then he's sleepy and he falls asleep again even when I'm talking to him.'

The doctor smiles into the phone. Yet, just conceivably, if almost impossibly, the sleeping might be the beginning of a diabetic coma: the diabetes made manifest by the urinary infection. To be certain he must do another blood test for sugar.

At that gate where the badger stood, he pauses and looks down at the view with which they fell in love, and then he remembers her saying in a more intense, more sibilant voice than her ordinary one:

âAll we've got is each other. So we have to be very strict. We watch over each other carefully when we are ill, we do.'

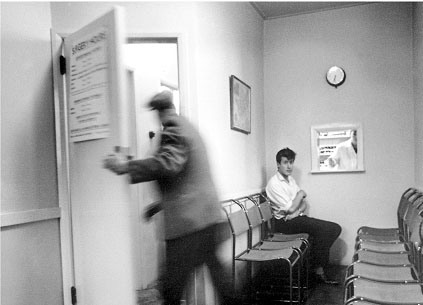

It is apart from the house: a building the size of two garages. It consists of a waiting-room, two consulting rooms and a dispensary. It is on the side of the hill which overlooks the river and the large wooded valley. From the other side of the valley it is almost too small to be visible.

On the door of the building is a notice which reads: Dr John Sassall M.B., Ch.B., D.Obst.R.C.O.G.

Â

Â

Â

The consulting rooms do not seem clinical. They seem lived-in and cosy. But they are neater than most living-rooms and, despite their smallness, there is more clear space. This is the working area where the patient is examined or treated or manipulated.

The rooms remind one of a ship's officer's cabin. There is the same cosiness, the same ingenuity in fitting many things into a small space, the same odd juxtaposition of domestic furniture and personal effects with instruments and appliances.

All this makes the examining couch look like a bunk. It has two sheets on it and an electric blanket. Whenever patients are due, Sassall switches the blanket on a quarter of an hour beforehand, so that if a patient has to strip and be examined, it will not strike as cold. He has a fastidious sense for detail. He is a short man; the chair in which the patients sit is exactly six inches lower than his own chair by the desk. Before he gives an injection he says: âYou'll just feel a tap.' As his hand comes down, holding the syringe, he opens his little finger and with the side of his hand flicks hard against the skin by the side of where the needle will go in a fraction of a second later, and this distracts the patient from registering the prick of the needle.