A Fortunate Man (6 page)

Authors: John Berger

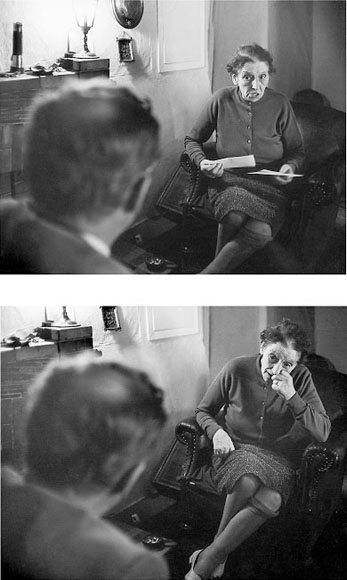

When Sassall emerged, he was still an extremist. He had exchanged an obvious and youthful form of extremism for a more complex and mature one: the life-and-death emergency for the intimation that the patient should be treated as a total personality, that illness is frequently a form of expression rather than a surrender to natural hazards.

This is dangerous ground, for it is easy to get lost among countless intangibles and to forget or neglect all the precise skills and information which have brought medicine to the point where there is the time and opportunity to pursue such intimations. The quack is either a charlatan or he is a healer who refuses to relate his own few insights to the general body of medical knowledge.

Sassall enjoyed this danger. Safe thinking was now like settling down ashore. âCommon-sense has been a dirty word with me for many years now â except perhaps when it is applied to very factual and easily assessed problems. When dealing with human beings it is my biggest enemy â and tempter. It tempts me to accept the obvious, the easiest, the most readily available answer. It has failed me on almost every occasion I have used it â and God knows how often I have fallen and still fall for the trap.'

Every week now he reads in considerable detail the three main medical journals, and from time to time goes on a refresher course at some hospital. He sees to it that he stays well-informed. But his satisfaction comes mostly from those cases where he faces forces which no previous explanation will exactly fit, because they depend upon the history of a patient's particular personality. He tries to keep that personality company in its loneliness.

He is acknowledged as a good doctor. The organization of his practice, the facilities he offers, his diagnostic and clinical skill are probably somewhat under-rated. His patients may not realize how lucky they are. But in a sense this is inevitable. Only the most self-conscious consider it lucky to have their elementary needs

met. And it is on a very basic, elementary level that he is judged a good doctor.

They would say that he was straight, not afraid of work, easy to talk to, not stand-offish, kind, understanding, a good listener, always willing to come out when needed, very thorough. They would also say that he was moody, difficult to understand when on one of his theoretical subjects like sex, capable of doing things just to shock, unusual.

How he actually answers their needs as a doctor is far more complicated than any of these epithets imply. To understand this we must first consider the special character and depth of any doctor-patient relationship.

The primitive medicine-man, who was often also priest, sorcerer and judge, was the first specialist to be released from the obligation of procuring food for the tribe. The magnitude of this privilege and of the power which it gave him is a direct reflection of the importance of the needs he served. An awareness of illness is part of the price that man first paid and still pays for his self-consciousness. This awareness increases the pain or disability. But the self-consciousness of which it is the result is a social phenomenon and so with this self-consciousness arises the possibility of treatment, of medicine.

2

We cannot imaginatively reconstruct the subjective attitude of a tribesman to his treatment. But within our culture today what is our own attitude? How do we acquire the necessary trust to submit ourselves to the doctor?

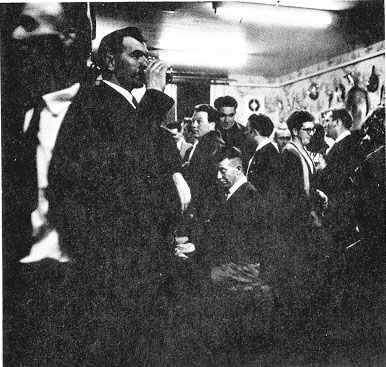

We give the doctor access to our bodies. Apart from the doctor, we only grant such access voluntarily to lovers â and many are frightened to do even this. Yet the doctor is a comparative stranger.

The degree of intimacy implied by the relationship is emphasized by the concern of all medical ethics (not only ours) to make an absolute distinction between the roles of doctor and lover. It is usually assumed that this is because the doctor can see women naked and can touch them where he likes and that this may sorely tempt him to make love to them. It is a crude assumption, lacking imagination. The conditions under which a doctor is likely to examine his patients are always sexually discouraging.

The emphasis in medical ethics on sexual correctness is not so much to restrict the doctor as to offer a promise to the patient: a promise which is far more than a reassurance that he or she will not be taken advantage of. It is a positive promise of physical intimacy without a sexual basis. Yet what can such intimacy mean? Surely it belongs to the experiences of childhood. We submit to the doctor by quoting to ourselves a state of childhood and simultaneously extending our sense of family to include him. We imagine him as an honorary member of the family.

In cases where the patient is fixated on a parent, the doctor may become a substitute for this parent. But in such a relationship the high degree of sexual content creates difficulties. In illness we ideally imagine the doctor as an elder brother or sister.

Something similar happens at death. The doctor is the familiar of death. When we call for a doctor, we are asking him to cure us and to relieve our suffering, but, if he cannot cure us, we are also asking him to witness our dying. The value of the witness is that he has seen so many others die. (This, rather than the prayers and last rites, was also the real value which the priest once had.) He is the living intermediary between us and the multitudinous dead. He belongs to us and he has belonged to them. And the hard but real comfort which they offer through him is still that of fraternity.

It would be a great mistake to ânormalize' what I have just said by concluding that quite naturally the patient wants a

friendly

doctor. His hopes and demands, however contradicted by previous

experience, however protected they may be by scepticism, however undeclared even to himself, are much more profound and precise.

In illness many connexions are severed. Illness separates and encourages a distorted, fragmentated form of self-consciousness. The doctor, through his relationship with the invalid and by means of the special intimacy he is allowed, has to compensate for these broken connections and reaffirm the social content of the invalid's aggravated self-consciousness.

When I speak of a fraternal relationship â or rather of the patient's deep, unformulated expectation of fraternity â I do not of course mean that the doctor can or should behave like an actual brother. What is required of him is that he should recognize his patient with the certainty of an ideal brother. The function of fraternity is recognition.