A History of the World in 100 Objects (31 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

The Han Chinese and the Roman empires covered roughly the same amount of land, but China was more populous. A census conducted in China only two years before the cup was made came up with the wonderfully precise figure of a population of 57,671,400 individuals. Roel Sterckx says:

One of the things we need to keep in mind is that the Chinese Empire is immense and that it straddles a hugely diverse geographic region. In the case of the Han we’re talking about a distance that stretches from North Korea to Vietnam. Contact between people is not always very obvious, so the circulation of goods, the circulation of imperially sanctioned objects, together with texts, is part of that symbolical assertion of what it means to be an empire. You might not see people who are part of the same empire, but you might actually, by witnessing the goods that are produced across the empire, feel or have a sense of belonging to that greater imagined community in many ways.

Fostering that sense of an imagined community was a key imperial strategy – and it didn’t come cheap. Typically, the emperor paid out a large chunk of state revenue each year to provide allies and vassal states with luxury gifts, including thousands of rolls of silk and hundreds of lacquer cups. So our cup is part of a system – it was given either as an imperial gift, or in lieu of a salary, to a senior official at the Han military garrisons near present-day Pyongyang in North Korea. Apart from its sheer monetary value, it was intended to bestow prestige and to suggest a personal link between the commander and the emperor.

At this point in the Han Dynasty’s history, however, the affairs of state were not in the hands of the emperor but of the dowager empress, the formidable Grand Empress Dowager Wang, who effectively ran the state for thirty years, as none of the emperors had much time or aptitude for business. She had one emperor son, who spent a good deal of time with his concubine, Flying Swallow (who, it was said, was so light that she could dance on the palm of his hand); one emperor grandson, who was besotted with his male lover; and another grandson, on the throne at the time of our cup, who had acceded at the age of 9 and was to be poisoned with pepper wine at the age of 15, two years after our cup was made. So this lacquer cup lived in interesting times, and its making was almost certainly organized by the Grand Dowager Empress.

The machinery of the state, including the production of luxury goods, was so well structured that it could work perfectly well despite such foibles at the top. This cup is remarkable for the supreme craftsmanship of its making, and even more so because it was subjected to a level of quality control that far exceeds that of most designer luxury objects today.

Chinese characters around the base of the cup tell us who was involved in its manufacture

Around the oval base of the cup runs a thin band with sixty-seven Chinese characters on it. In Europe you might expect this kind of band to be a motto or a dedication, perhaps, but here the characters list six craftsmen responsible for the different processes involved in manufacturing the cup – making the wooden core, undercoat lacquering, top-coat lacquering, gilding the ear-handles, painting and final polishing. And then – this could surely happen only in China – it goes on to list the seven product inspectors, whose responsibility was to guarantee quality. Six craftsmen, and seven supervisors – this is the stuff of real bureaucracy. The list reads:

The wooden core by Yi, lacquering by Li, top-coat lacquering by Dang, gilding of the ear-handles by Gu, painting by Ding, final polishing by Feng, product inspection by Ping, supervisor-foreman Zong. In charge were Government Head Supervisor Zhang, Chief Administrator Liang, his deputy Feng, their subordinate Executive Officer Long and Chief Clerk Bao.

This cup is a powerful document of the link between artisanal production and state administration; bureaucracy as a guarantee of beauty. It’s not something familiar to the modern European, but for the journalist and China expert Isabel Hilton it’s a continuing tradition in Chinese history:

In Han times, the government had a major role in industry, partly to deal with its military expenditure in order to finance the kind of expeditions that it required against the aggressive peoples of the north and the west. The government nationalized some major industries and it regulated major industries for quite a long time, so they were often run by private entrepreneurs or people who had been entrepreneurs, but under state control. There are modern parallels here, because what we’ve seen in the past few decades is the emergence of a hybrid system in China, from an economy that was completely under state control to a more market-oriented model, but nevertheless very firmly under state direction. If you look at where the capital gets invested, and what the structure of ownership is in Chinese industry, it is still largely state-controlled.

So, exploring this lacquer cup of 2,000 years ago takes us into territory that is disconcertingly familiar – private enterprise under Chinese state control, cutting-edge mass production allied to high technology, deft management of relations between the Chinese capital and North Korea, and the skilful deployment of diplomatic gifts. The Chinese still know that the best gifts are always the ones that only the giver can command. In the time of the Han Dynasty, that was silk and lacquer cups. Today, when China wants to establish friendly relations, it still gives the present that nobody else can match – it’s known as Panda Diplomacy.

Head of Augustus

27–25

BC

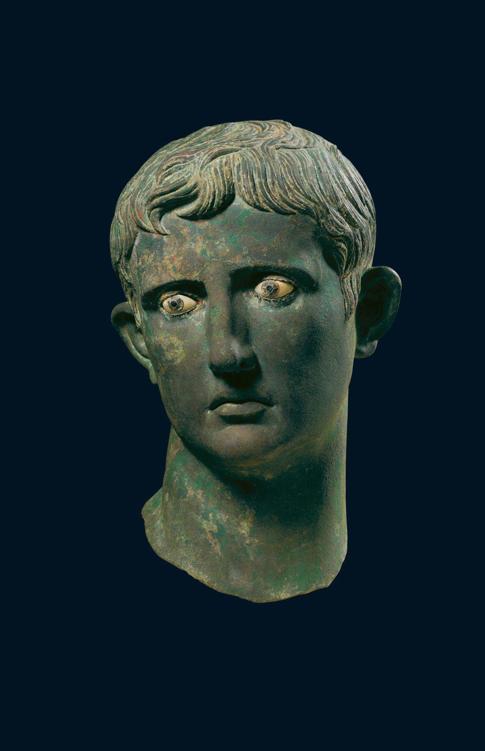

Caesar Augustus, the first Roman emperor, is one of the most famous leaders in the history of the world. We have his bronze head here in the Roman galleries in the British Museum. Although tarnished, it radiates charisma and raw power. It is impossible to ignore. The eyes are dramatic and piercing; wherever you stand, they won’t look at you. Augustus is looking past you, beyond you, to something much more important: his future.

The curling hair is short and boyish, slightly tousled, but it’s a calculated tousle – one that clearly took a long time to arrange. This is an image that has been carefully constructed, projecting just the right mix of youth and authority, beauty and strength, will and power. The portrait was very recognizable at the time, and it’s proved very enduring.

His head is a bit over life-size and tilted as if he’s in conversation, so for a moment you could believe that he’s just like you and me – but he’s not. This is the Roman emperor who ruled at the time Christ was born. The image presents him when he has recently defeated Antony and Cleopatra and has conquered Egypt; he is well on his way now to imperial glory and is firmly embarked on an even greater journey – to becoming a god.

In previous chapters I’ve looked at how rulers commissioned objects that asserted their power – somewhat obliquely and essentially by association. But this is something completely different – a ruler who uses his own body and his own likeness to assert his personal power. His bronze, larger-than-life head gives a brutally clear message: I am great, I am your leader, and I stand far above everyday politics. And yet, ironically, we have this commanding head here at the Museum only because it was captured by an enemy and then humiliatingly buried. The glory of Augustus is not quite as unalloyed as he wanted us to believe.

Augustus was Julius Caesar’s great-nephew. The assassination of Caesar in 44

BC

left him the heir to Caesar’s fortune and to his power. He was only 19 when suddenly he was catapulted into a key role in the politics of the Roman Republic.

Known at that point as Octavian, Augustus quickly outshone his peers in the scramble for absolute power. The pivotal moment in his rise was the defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31

BC

. Already holding Italy, France, Spain, Libya and the Balkans, Augustus now followed the example of Alexander the Great and seized the richest prize of them all – Egypt. The immense wealth of the Nile kingdom was at his disposal. He made Egypt part of Rome – and then turned the Roman Republic into his personal empire. Across that empire, statues of the new ruler were erected. There were already hundreds of statues portraying him as Octavian, the man-of-action party leader; but in 27

BC

the Senate acknowledged his political supremacy by awarding him the honorific title of Augustus – ‘the revered one’. This new status called for a quite different kind of image, and that is what our head shows.

Our head was made a year or two after Augustus became emperor. It was part of a full-length, slightly larger-than-life statue that showed him as a warrior. It’s broken off at the neck, but otherwise the bronze is in very good condition. This image, in one form or another, would have been familiar to hundreds of thousands of people, because statues like this were set up in cities all over the Roman Empire. This is how Augustus wanted his subjects to see him. And although every inch a Roman, he wanted them to know that he was also the equal of Alexander and heir to the legacy of Greece. The Roman historian Dr Susan Walker explains:

When he had become master of the Mediterranean world and took the name Augustus, he really needed a new image. He couldn’t copy Caesar’s image, because Caesar looked like a crusty old Roman; he had a real warts-and-all portrait, very thin and scraggy, and bald – and very austere, very much in the manner of traditional Roman portraiture. That image had become a little bit discredited, and in any case Augustus, as he now was, was setting up an entirely new political system, so he needed a new image to go with it. Having assumed this image when he was still in his thirties, he stayed with it until he died aged 76; there’s no suggestion in his portraits of any ageing process at all.

This was an Augustus for ever powerful, for ever young. His deft, even devious, mix of patronage and military power, which he concealed behind the familiar offices of the old Republic, has served as a model and a masterclass for ambitious rulers ever since. He built new roads and established a highly efficient courier system, not only so that the empire could be ruled effectively from the centre but also so that he could be visible to his subjects everywhere. He reinvigorated the formidable army to defend and even extend the imperial borders, establishing a long-lasting peace during his forty years of steady rule. This golden period of stability and prosperity began what is famously known as the ‘Pax Romana’. Having brutally fought and negotiated his way through to the top, once he was there Augustus wanted to reassure people that he would not be a tyrant. So he set to work to make people believe in him. He brilliantly turned subjects into supporters. I asked Boris Johnson, the Mayor of London and a Classicist, how he rated Augustus:

Well, he was about the greatest politician the world has ever seen. If you wanted to have a first eleven of the world’s leading politicians, the most accomplished diplomats and ideologues of all time, you’d have Augustus as your kind of midfield playmaker, captain of the eleven.

He became a vital part of the glue that held the whole Roman Empire together. You could be out there in Spain or Gaul, and you could go to a temple and you would find women with images of Augustus, of this man, of this bust sewn on to their cowls. People at dinner parties in Rome would have busts exactly like this above their mantelpieces – that was how he was able to enthuse the entire Roman Empire with that sense of loyalty and adherence to Rome. If you wanted to become a local politician, in the Roman Empire, you became a priest in the cult of Augustus.