A History of the World in 100 Objects (28 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

And bells are still going strong. The ancient bells used for the 1997 Hong Kong ceremony were played again at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing. And Confucius is now, it seems, the flavour of the decade. He has his own $25 million biopic, a bestselling book, a TV series and a hundred-part animated series on his teachings. The age of Confucius has come again.

Empire Builders

300

BC–AD

10

Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Persian Empire in 334

BC

ushered in an age of megalomaniac rulers and great empires. Although there had been empires before, this was the first time regional superpowers emerged in different parts of the globe. In the Middle East and the Mediterranean, Alexander became a model for rulers to emulate or reject: Augustus, the first Roman emperor, imitated Alexander by using his own image to represent imperial power to his subjects. In contrast, the Greek rulers of Egypt looked back to Egypt’s past in times of political weakness, and in India the Emperor Ashoka rejected oppressive rule altogether, promoting his peaceful philosophy through inscriptions on pillars across the subcontinent. While Ashoka’s empire did not last long beyond his lifetime, his ideals survived. The Roman Empire continued for the next 400 years, rivalled in size, population and sophistication only by the Han Dynasty in China, where the state produced luxury goods to win both admiration and obedience.

Coin with Head of Alexander

MINTED

305–281

BC

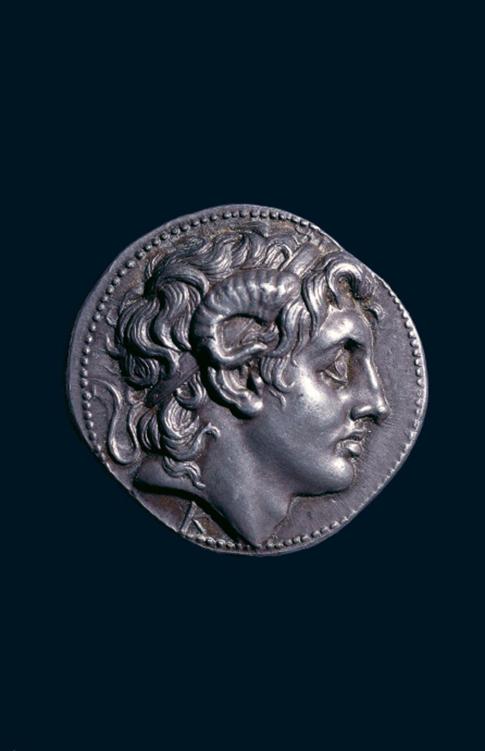

Just over 2,000 years ago there were, in Europe and Asia, great empires whose legacies are still strongly felt in the world today – the Roman Empire in the West, the empire of Ashoka in India and the Han Dynasty in China. I want to examine how power in such empires is constructed and projected. Military might is just the beginning – it’s the easy part. How does a ruler stamp his authority on the very minds of his subjects? In this area images are generally more effective than words, and the most effective of all images are those we see so often that we hardly notice them: coins. So the ambitious ruler shapes the currency: the message is on the money, and that message can live on long after the ruler is dead. Although this silver coin shows the image of Alexander the Great, it was struck at least forty years after his death, on the orders of one of his successors, Lysimachus.

The coin is about 3 centimetres (just over an inch) in diameter, slightly larger than a 2p piece. It bears the profile of a young man, with straight nose and strong jaw line, showing Classical good looks and strength. He’s gazing keenly into the distance; the tilt of the head is commanding, suggestive of vigorous forward movement. It is an image of a dead leader, but one clearly intended to carry a political message of power and authority now.

You find exactly the same phenomenon in modern China, where the red currency notes carry the portrait of Chairman Mao. It could seem strange that the very lifeblood of what is now a spectacularly successful capitalist economy, its money, carries on it the portrait of a dead Communist revolutionary. Yet the reason is clear. Mao reminds the Chinese people of the heroic achievements of the Communist Party, which is still in power. He stands for the recovery of Chinese unity at home and prestige abroad, and every Chinese government wants to be seen as the inheritor of his authority. This appropriation of the past, this kind of exploitation of a dead leader’s image, is nothing new. It has been around for thousands of years, and what’s happening today to Mao on the Chinese currency was happening more than 2,000 years ago to Alexander.

Minted around 300

BC

, this is one of the earliest coins to carry the image of a leader. Alexander the Great, whose head is represented on the coin, was the most glamorized military ruler of his age – possibly of all time. We’ve got no way of knowing whether this is an accurate likeness of Alexander, but it must be him, because as well as human hair this man has ram’s horns. It is the horn symbol, well known throughout the ancient world, that leaves the viewer in no doubt that we are looking at an image of Alexander. The horns are associated with the god Zeus-Ammon – a hybrid of the two leading Greek and Egyptian gods, Zeus and Ammon. So this small coin is making two big statements – it asserts Alexander’s dominion over both Greeks and Egyptians, and it suggests that, in some sense, he is both man and god.

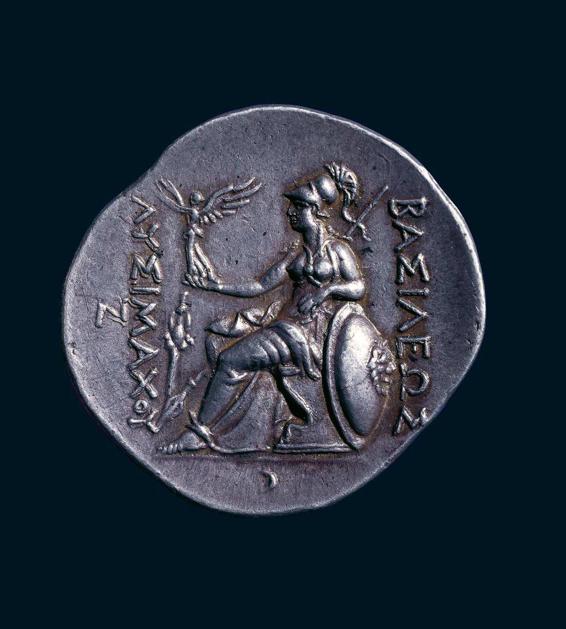

The reverse of the coin shows Athena Nikephoros, and Greek letters spell ‘of King Lysimachus’

Alexander the man was the son of Philip II of Macedon, a small kingdom a few hundred miles north of Athens. Philip expected great things of his son, and he employed the great philosopher Aristotle as his tutor. Alexander came to the throne in 336

BC

at the age of 20, with an almost limitless sense of self-belief. His stated goal was to reach the ‘ends of the world and the Great Outer sea’, and to do this he embarked on a series of wars, first crushing rebellions by Athens and the other Greek cities, then turning east to confront the long-standing enemy of the Greeks – Persia. Persia controlled at that point the greatest empire on earth, sprawling from Egypt across the Middle East and central Asia to India and almost to China. The young Alexander campaigned brilliantly for a total of ten years, until he defeated the whole of the Persian Empire. He was clearly a driven man. What drove him on? We asked the leading expert on Alexander, Robin Lane Fox:

Alexander was driven by the heroic ideals that befitted a Macedonian king, ruling over Macedonians, the ideals of personal glory, prowess; he was driven by a wish to reach the edge of the world, he was driven by a wish to excel for ever his father, Philip, who was a man of significance but who pales almost to a shadow beside Alexander’s global reputation.

Alexander’s victories didn’t just depend on his armies. They required money – and lots of it. Luckily, Philip had conquered the rich gold and silver mines of Thrace, the area that straddles the modern borders of Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey. That precious metal financed the early campaigns, but this inheritance was later swelled by the colossal wealth Alexander captured in Persia. His imperial conquests were bankrolled by nearly five million kilos of Persian gold.

With irresistible force, huge wealth and enormous charisma, it’s no wonder that Alexander became a legend, seeming to be more than mortal, literally superhuman. In one of his early campaigns into Egypt, he visited the oracle of the god Ammon, which named him not just the rightful pharaoh, but a god. He left the oracle with the title ‘son of Zeus-Ammon’, which explains the characteristic ram’s horns in images of him like the one on our coin. He was received by many of the conquered peoples as though he were a living god, but it’s not altogether clear whether he actually believed himself to be one. Robin Lane Fox suggests he saw himself more as the son of god:

He certainly believed he was the son of Zeus, [that] in some sense, Zeus had entered into his begetting, a story possibly told to him by his mother Olympias herself, though he is, in earthly terms, the son of the great king Philip. He is honoured as a god, spontaneously, by some of the cities in his empire, and he is not displeased to receive honours equal to the gods. But he knows he’s mortal.

Alexander conquered an empire of more than two million square miles and founded many cities in his name, the most famous being Alexandria in Egypt. Although nearly every large museum in Europe has an image of Alexander in its collection, they are not consistent and there’s no way of knowing whether he looked like any of them. It was only after Alexander’s death in 323

BC

that an agreed, idealized image, constructed for public consumption, came into being – and that’s the image found on our coin. The reverse of the coin reveals that this is not Alexander’s coin at all – he’s making a posthumous guest appearance in somebody else’s political drama.

The other side of the coin shows the goddess Athena Nikephoros, bringer of victory, carrying her spear and shield. She is the divine patroness of Greeks and a goddess of war. But it’s not Alexander that she’s favouring, because the Greek letters beside her tell us that this is the coin of King Lysimachus. Lysimachus had been one of Alexander’s generals and companions. He ruled Thrace from Alexander’s death until his own death in 281

BC

. Lysimachus didn’t mint a coin that showed himself. He decided instead to appropriate the glory and the authority of his predecessor. This is image manipulation – almost identity theft – on a heroic scale.

Alexander died in his early thirties, and his empire quickly disintegrated into a confusion of shifting territories under competing warlords – Lysimachus was just one of them. All of the warlords claimed that they were the true heirs of Alexander, and many of them minted coins with his image on them to prove it. This was a struggle fought out not just on the battlefield but on the currency. It’s a textbook early example of a timeless political ploy: harnessing the authority and the glamour of a great leader of the past to boost yourself in the present.

Dead reputations are usually more stable and more manageable than living ones. Since the Second World War, for example, Churchill and de Gaulle have been claimed by British and French political leaders of all hues when it suited the day’s agenda. But in democratic societies, this is a high-risk strategy, as the political commentator and broadcaster Andrew Marr points out:

The more democratic a culture is, the harder it is to appropriate a previous leader. It’s very interesting at the moment to see the revival of Stalin as an admired figure in Putin’s Russia, having been knocked down as a bloodthirsty tyrant before. So the possibility of taking a figure from the past is always open, but the more conversational, the more confrontational, more democratic, the more argumentative a political culture is, the harder it is. You can see this in the case of Churchill, because there are still lots and lots of people who know a great deal about what Churchill thought and said. Any mainstream party which tried to say ‘we are the party of Churchill’ would get into trouble because Churchill changed his mind so much that he can be quoted against you as often as he can be quoted in favour of you.

Dead rulers are still very present, and they’re still on the currency. A thoughtful alien handling the banknotes of China and the United States today might well assume that one was ruled by Mao and the other by George Washington. And, in a sense, that’s exactly what the Chinese and American leaders want us all to think. Political giants like these lend an aura of stability, legitimacy and above all unquestionable authority to modern regimes struggling with huge problems. Lysimachus’s gambit still sets the pace for the world’s superpowers.

And it worked for Lysimachus himself – up to a point. He’s a mere historical footnote in comparison to Alexander; he didn’t get an empire, but he did get a kingdom, and he hung on to it. Twenty years after Alexander’s death, it was clear that his empire would never be reconstituted, and for the next 300 years the Middle East would be ruled by many cultured but competitive Greek-speaking kings and dynasties. The most famous monument of any of these Greek-speaking states, the Rosetta Stone, features in

Chapter 33

. But my next object comes from India, where the great emperor Ashoka linked himself to a different kind of authority to strengthen his political position – not the authority of a great warrior, but one of the greatest of all religious teachers – the Buddha.