A History of the World in 100 Objects (24 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

I want to explore that empire in this tiny golden chariot, pulled by four golden horses. It’s easy to imagine a chariot like this racing along the great Persian imperial roads. There are two figures in it: the driver, who stands holding the reins, and the much larger and clearly very important passenger, who sits on a bench at his side. He is probably meant to be a senior administrator, visiting the distant province that he rules on behalf of the king of Persia.

The model was indeed found in a very distant province, on the far eastern edge of the empire, near the borders of modern Tajikistan and Afghanistan. It’s part of a huge hoard of gold and silver objects, known as the Oxus treasure, that for more than a hundred years have formed one of the great collections at the British Museum.

This exquisite chariot sits quite comfortably on the palm of the hand, where it looks like an expensive toy for a privileged child. We can’t, however, be certain that it was in fact a toy; it could have been made as an offering to the gods, either asking them for a favour or thanking them for one. But whatever it meant then, this chariot today allows us today to conjure up an empire.

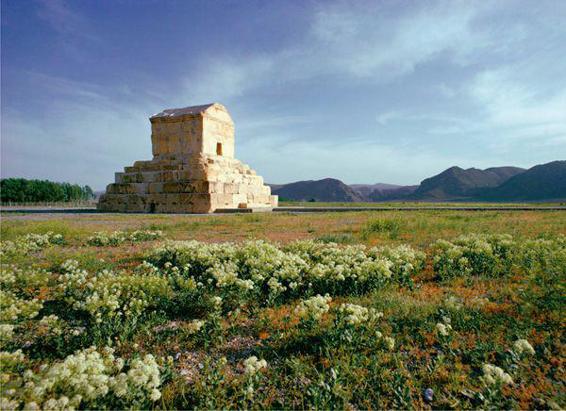

What kind of an empire was it? About 70 miles north of Shiraz, in Iran, the low camel-coloured hills open out into a flat windy plain. In this featureless landscape is a huge stone plinth, rising in six gigantic steps to what looks like a gabled hermit’s cell. It dominates the entire landscape. It is the tomb of Cyrus, the first Persian emperor, the man who 2,500 years ago built the largest empire that the world had then seen, and changed the world – or at least the Middle East – for ever.

Centred on modern Iran, the vast Persian Empire ran from Turkey and Egypt in the west to Afghanistan and Pakistan in the east. To control an empire like this required land transport on a quite unprecedented scale; the Persian Empire is the first great ‘road’ empire of history.

The Persian Empire was more a collection of kingdoms than what we might immediately think of as an empire. Cyrus called himself the Shahanshah – the King of Kings – making clear that this was a confederation of allied states, each with its own ruler but all under firm Persian control. It was a model that allowed a great deal of local autonomy and all sorts of diversity – very different from the later Roman model. The historian and writer Tom Holland elaborates:

Persian occupation could be compared to a light morning mist settling over the contours of their empire – you were aware of it, but it was never obtrusive.

The Roman approach was to encourage those they had conquered to identify with their conquerors, so that ultimately everyone within the borders of the Roman Empire came to consider themselves to be Romans. Persians went for a very different approach. So as long as you paid your taxes, and you didn’t revolt, then you’d pretty much be left alone. That said, however, you do not conquer a vast empire without spilling an immense amount of blood, and there was no question that if you dared to stand up to the Persian kings then you would be obliterated.

They obliterated troublesome people by sending armies along those wonderfully straight and fast imperial roads. But inside the empire bloodshed was generally avoided, thanks to a huge – and hugely effective – administrative machine. The King of Kings ultimately controlled everything, but at the local level he was represented by a governor – a satrap – who would keep a close eye on what was going on in the subordinate kingdoms. He would enforce law and order, levy taxes and raise armies.

The tomb of Cyrus the Great, king of Persia

Which brings us back to our golden toy, because the passenger in our chariot must be a satrap on tour. He sports a stylishly patterned overcoat – he’s obviously spent a great deal of money on it – and his headdress leaves you in no doubt that this is a man who is used to being in charge. His chariot is made for serious travel: the large-spoked wheels are as high as the horses themselves, and are clearly designed for long distances.

You can tell a lot about a state from its transport system, and our chariot tells us a great deal about imperial Persia. Public order was so secure that people could travel long distances without armed guards. And they could travel fast. With its horses specially bred for strength and speed, and with its large, steadying wheels, this chariot was the Ferrari or Porsche of its time. Broad dirt roads were kept wheel-worthy in all weathers, and there were frequent staging posts. Commands from the centre could be transmitted at speed across the whole territory, thanks to an entirely reliable royal postal service that used horsemen, runners and express messengers. Foreign visitors were deeply impressed, among them the Greek historian Herodotus:

There is nothing in the world which travels faster than these Persian couriers … it is said that men and horses are stationed along the road, equal in number to the number of days the journey takes – a man and a horse for each day. Nothing stops these couriers from covering their allotted stage in the quickest possible time – neither snow, rain, heat, nor darkness.

But our chariot doesn’t just tell us about travel and communications; it sums up the acceptance of diversity that was at the heart of the Persian imperial system. Although found on the eastern frontier near Afghanistan, it must have been made in central Persia because of the technique of its metalworking. The driver and his passenger wear the costume of the Medes, an ancient people who lived in the north-west of what is now Iran, while on the front of the chariot, prominently displayed, is the head of the Egyptian god Bes. Bes, a dwarf with bow legs, is perhaps not your most likely candidate for a divine protector, but he looked after children and people in trouble, and he was a good god to have guarding your chariot on long journeys. I suppose he’s the equivalent of a modern-day St Christopher or talisman dangling from the car mirror.

But what is an Egyptian god doing protecting a Persian on the frontiers of Afghanistan? It’s a perfect demonstration of the Persian Empire’s striking capacity for tolerating different religions and indeed, on occasion, adopting them from the people that they conquered. This unusually inclusive empire was also perfectly happy to use foreign languages for official proclamations. Here is Herodotus again:

No race is so ready to adopt foreign ways as the Persian; for instance, they wear the Median costume as they think it handsomer than their own, and their soldiers wear the Egyptian corselet.

The multi-faith, multicultural approach that’s summed up in our little chariot, when combined with well-organized military power, created a flexible imperial system that lasted for more than 200 years. It enabled the king to present to his subjects the image of a tolerant, accommodating empire, whatever the specific facts on the ground might have been. So, when Cyrus invaded Babylon, near modern Baghdad, in 539

BC

, he could issue a grandiloquently generous decree – in Babylonian – presenting himself as the defender of the peoples that he had just conquered. He restored the cults of different gods and allowed the people taken prisoner by the Babylonians to return to their homelands. In his own words:

When my soldiers in great numbers peacefully entered Babylon … I did not allow anyone to terrorize the people … I kept in view the needs of the people and all their sanctuaries to promote their well-being … I freed all slaves.

The most famous beneficiaries of Cyrus’s shrewd political judgement after the conquest of Babylon were the Jews. Taken prisoner a generation before by Nebuchadnezzar, they were now allowed to return home to Jerusalem and to rebuild their temple. It was an act of generosity that they never forgot. In the Hebrew scriptures Cyrus is hailed as a divinely inspired benefactor and hero. In 1917, when the British government declared that it would establish in Palestine a national home to which Jews could once again return, images of Cyrus were displayed alongside photographs of George V throughout eastern Europe. Not many political gambits are still paying dividends 2,500 years later.

One of the perplexing things about the Persian Empire, though, is that the Persians themselves wrote very little about how they managed it. Most of our information comes from Greek sources. As the Greeks were for long the enemies of the Persians, it’s rather as if we knew the history of the British Empire only through documents written by the French. But modern archaeology has provided new sources of information, and in the past fifty years the Iranians themselves have rediscovered and reappropriated their great imperial past. Any visitor to Iran today feels it at once. Michael Axworthy explains:

There is a huge and unavoidable pride in the past in Iran … It’s a culture that is at ease with complexity, that has faced the complexity of different races, different religions, different languages, and has found ways to encompass them and to relate them to each other and to organize them. Not in a loose way or in a relativistic way, necessarily, but in a principled way that keeps things together. And Iranians are very keen for people to understand that they have this long, long, long history and this ancient heritage.

Axworthy’s phrase ‘empires of the mind’ sums up pretty well the theme that I’m trying to tackle in these chapters, but perhaps ‘states of mind’ would be more accurate – because I’m discussing objects that show us how different people imagine and devise an effective state. For Persia I’ve been looking at a toy chariot; for Athens I’ll be looking at a temple. As you’d imagine, because they for so long were at war, Greeks and Persians had very different ideas of what a state should be. But precisely because they were at war, each tended to define the ideal state in opposition to the other. In 480

BC

Persian troops destroyed the temples on the Athenian Acropolis. In its place the Athenians built the Parthenon that we know today.

There are few objects that over the last 200 years have been so widely seen as embodying a set of ideas as the Parthenon. And I’ll be discussing one of the sculptures that decorated it next.

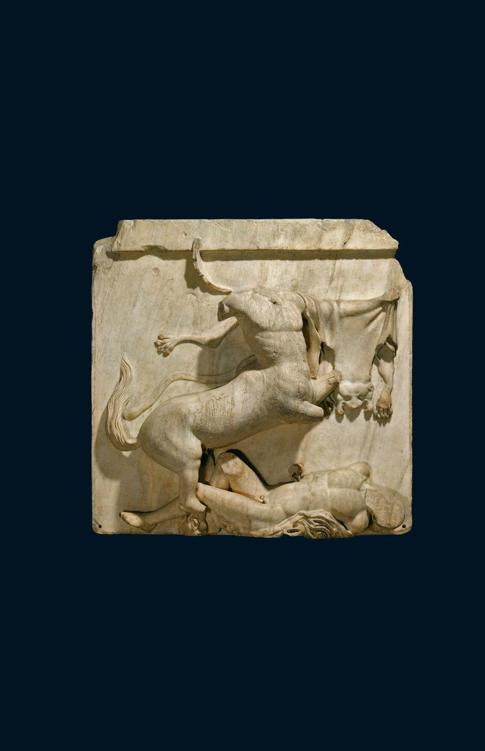

Parthenon Sculpture: Centaur and Lapith

AROUND

440

BC

Around 1800, Lord Elgin, the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, removed some of the sculptures from the ruins of the Parthenon in Athens, and a few years later put them on public show in London. For most western Europeans it was the first time they had ever been able to look closely at Greek sculpture, and they were overwhelmed and inspired by the vitality and the beauty of these works. But in the twenty-first century, the Elgin Marbles, as they have long been known, are famous less as art objects than as the focus of political controversy. For most people today, the Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum provoke only one question: should they be in London or in Athens? The Greek government insists they should be in Athens; the British Museum’s Trustees believe that in London they’re an integral part of the story of world cultures.

It’s a passionate debate in which everyone has a view; but I want to focus on one sculpture in particular, and what that sculpture meant to the people who made it and looked at it in Athens in the fifth century

BC

.

The Parthenon sculptures set out to present an Athenian universe made up of gods, heroes and mortals, woven together in complex scenes drawn from myth and daily life. They are some of the most moving and uplifting sculptures ever made. They’ve become so familiar, and have shaped so much of European thinking, that it’s hard now to recover their original impact. But at the time of their making they were a quite new vision of what it meant, intellectually and physically, to be human and, indeed, Athenian. They’re the first, and supreme, achievements of a new visual language. Olga Palagia, Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Athens, puts them in perspective: