A History of the World in 100 Objects (60 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

It was another thousand years before European sailors matched the Polynesian feats of navigation, and when they reached Rapa Nui on Easter Day 1722 they were astonished to find a large population already established. Even more astonishing were the objects that the inhabitants had made. The great monoliths of Easter Island are like nothing else in the Pacific, or indeed anywhere, and they’ve become some of the most famous sculptures in the world. This is one of them. He’s called Hoa Hakananai’a – the name has been roughly translated as ‘hidden friend’. He came to London in 1869, and he has been one of the most admired inhabitants of the British Museum ever since.

It is a constant of human history that societies devote huge amounts of time and resource to ensuring that the gods are on their side, but few societies have ever done it on such a heroic scale as those of Rapa Nui. The population was probably never any more than about 15,000, but in a few hundred years the inhabitants of this tiny island quarried, carved and erected more than a thousand massive stone sculptures. Hoa Hakananai’a was one of them. He was probably made around the year 1200, and was almost certainly intended to house an ancestral spirit: he is a stone being, which an ancestor may from time to time visit and inhabit.

Standing below him you are immediately conscious of the solid basalt rock he is made out of. Although we see him only from the waist up, he is about 2.7 metres (9 feet) high and dominates whatever gallery he’s in. When you’re working hard stone like this and have only stone tools to chip away with, you can’t do detail, so everything about this giant had to be big – and bold. The heavy rectangular head is huge, almost as wide as the torso below. The overhanging brow is one straight line running across the whole width of the head. Below it are cavernous eye sockets and a straight nose with flaring nostrils. The square jaw juts assertively forward and the lips are closed in a strong frowning pout. In comparison to the head, the torso is only sketched in. The arms are barely modelled at all and the hands disappear into the stone block of a swelling paunch. The only details on the body are the prominent nipples.

Hoa Hakananai’a is a rare combination of physical mass and evocative potency. For the sculptor Sir Anthony Caro, this is the essence of sculpture:

I see sculpture, the setting up of a stone, as a basic human activity. You’re investing that stone with some sort of emotive power, some sort of presence. That way of making a sculpture is a religious activity. What the Easter Island sculpture does is give just the essence of a person. Every sculptor since Rodin has looked to primitive sculpture, because all the unnecessary elements are removed. Anything that is left in is what stresses the power of the stone. We are down to the essence; its size, its simplicity, its monumentality and its placement – those are all things that matter.

The statues were placed on specially built platforms ranged along the coastline – a sacred geography reflecting the tribal divisions of Rapa Nui. Moving these statues would have taken days and a large workforce. Hoa Hakananai’a would have stood on his platform with his giant stone companions in a formidable line, their backs to the sea, keeping watch over the island. These uncompromising ancestor figures must have made a haunting – and daunting – vision to any potential invaders and a suitably imposing welcome party for any visiting dignitaries. They have also been credited with a whole range of miracle-working powers. The anthropologist and art historian Professor Steven Hooper explains:

It was a way of human beings who were alive relating to and exchanging with their ancestors, who have very great influence on human life. Ancestors can affect fertility, prosperity, abundance. They are colossal. This one in the British Museum is relatively small – there is one unfinished in a quarry in Easter Island that is over 70 feet tall – how they ever would have erected it goodness only knows! It does put me in mind of medieval cathedral-building in Europe or in Britain, where you have extraordinary constructions involving enormous amounts of time and labour and skill … it’s almost as if these sculptures scattered around the slopes of Easter Island, large sculptures, are equivalent to these medieval churches. You don’t actually need them all, and they are sending messages not only about piety, but also about social and political competition.

So there was a populous island, effectively organized, practising religion in a carefully structured, competitive way. And then, it seems quite suddenly around 1600, the monolith-making stopped. No one has a very clear idea why. Certainly all islands like this are fragile ecosystems, and this one was being pushed beyond what was comfortably sustainable. The islanders had gradually cut down most of the trees and had hunted land birds almost to extinction. The sea birds, above all the sooty terns, moved away to nest on safer offshore rocks and islands. It must have seemed as if the favour of the gods was being withdrawn.

Where the people of Constantinople confronted crisis by looking back to an old religious practice, the inhabitants of Rapa Nui invented a new one, turning to a ritual that, not surprisingly, was all about scarce resources. The Birdman cult, as it has been called, focused on an annual competition to collect the first egg of the migrating sooty tern from a neighbouring islet. The man who pulled off the feat of bringing an egg back, unbroken, through the sea and over cliffs, would for a year become the Birdman. Invested with sacred power, he would live in isolation, grow his nails like bird talons and wield a ceremonial paddle as a symbol of prestige. Surprisingly, we can tell this story, and the change in religious practice, through our sculpture. Rather than being abandoned along with the other monoliths, Hoa Hakananai’a was incorporated into the Birdman cult, was moved, placed in a hut and now entered a new phase of his life.

The back of Hoa Hakananai’a, with symbols of the birdman cult in low relief

All the key elements of this later ritual are present in our statue, carved on his back. They must have been added several hundred years after the statue was first made, and the carving style here could hardly be more different from that of the front. It is in low relief, the scale is small, and the sculptor has tried to accommodate a large range of disparate details. Each shoulder blade has been turned into a symbol of the Birdman; two frigate birds with human arms and feet face each other, their beaks touching at the back of the statue’s neck. On the back of the statue’s head are two stylized paddles, each with what looks like a miniature version of our statue’s face at the upper end, and between the paddles is a standing bird which is thought to be a young sooty tern, whose eggs were so central to the Birdman ritual. This carving on the back of the statue could never have been very legible as sculpture. We know it was painted in bright colours, so that this cluster of potent symbols could be easily recognized and understood. Now, without its colour, the carving looks to my eyes feeble, fussy, diminished – a confused and timid postscript to the confident vigour of the front.

It is seldom that you see ecological change recorded in stone. There is something poignant in this dialogue between the two sides of Hoa Hakananai’a, a sculpted lesson that no way of living or thinking can endure forever. His face speaks of the hope we all have of unchanging certainty; his back of the shifting expediencies that have always been the reality of life. He is Everyman.

And Everyman is usually a survivor. The Easter Islanders seem to have adapted reasonably well to their changing ecological circumstances, as Polynesians have always had to. But in the nineteenth century there were challenges of a completely different order – from across the sea came slavery, disease and Christianity. When the British ship HMS

Topaze

arrived in 1868, there were only a few hundred people left on the island. The chiefs, by now baptized, presented Hoa Hakananai’a to the officers of the

Topaze

. We don’t know why they wanted him to leave the island, but perhaps the old ancestral sculpture was seen as a threat to the new Christian faith. A troop of islanders moved him to the ship, and he was taken to England to be presented to Queen Victoria, and then sent to be housed at the British Museum. He faces south-east, looking towards Rapa Nui, 14,000 kilometres (8,500 miles) away.

Hoa Hakananai’a now stands in the gallery devoted to Living and Dying, surrounded by objects that show how other societies in the Pacific and the Americas have addressed the predicaments that confront humanity everywhere. He is a supremely powerful statement of the fact that all societies keep looking for new ways to make sense of their changing world and to ensure that they survive in it. In 1400, none of the cultures shown in this gallery were known to Europeans. But this was about to change. In the rest of this history, we will be looking at the way in which these many different worlds – even islands as remote as Rapa Nui – became, whether they wanted to or not, integral parts of one global system. It’s a history that is in many ways familiar, but, as always, objects have the power to engage, to surprise and to enlighten.

The Threshold of the Modern World

AD

1375–1550

For thousands of years objects had travelled huge distances over land and sea. In spite of these connections, the world before 1500 was essentially still a series of networks. Nobody could take a global view because nobody had ever travelled round the world. These chapters are about the great empires of the world at that last pre-modern moment, when it was still unthinkable for one person to visit them all, and when even superpowers dominated only their regions.

Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent

AD

1520–1566

Between about 1350 and 1550 great swathes of the world were occupied by the superpowers of their day – from the Inca in South America to the Ming in China, the Timurids in central Asia and the vigorous Ottoman Empire, which spanned three continents and ran from Algiers to the Caspian, from Budapest to Mecca. Two of these empires lasted for centuries; the other two collapsed within a couple of generations. The ones that lasted endured not only by the sword but also by the pen – that is, they had flourishing and successful bureaucracies which could sustain them through tough times and incompetent leaders. The paper tiger, paradoxically, is the one that lasts. The enduring power we are looking at in this chapter is the great Islamic Ottoman Empire, which by 1500 had conquered Constantinople and was moving, with the confidence born of secure borders and expanding strength, from being a military power to an administrative one. In the modern world, as the Ottomans demonstrated, paper is power.

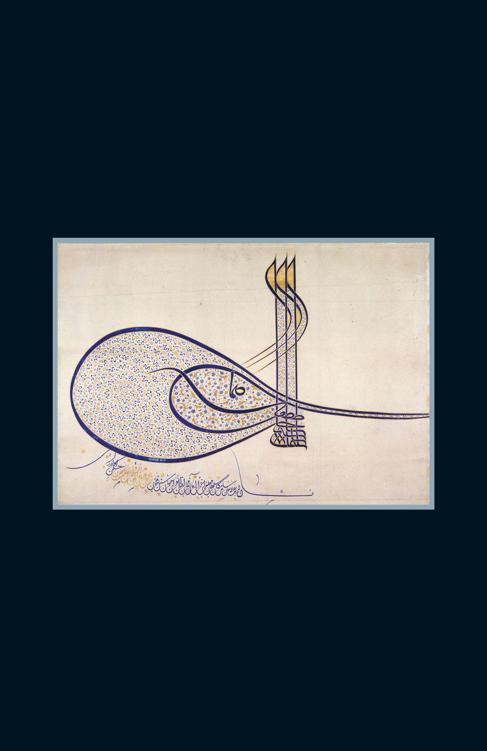

And what a piece of paper this is. It is a very beautiful painted drawing – it is a badge of state, a stamp of authority and a work of the highest art. It is called a tughra. This tughra has been drawn on heavy paper in bold lines of blue cobalt ink, enclosing what looks like a tiny meadow of colourful, golden flowers. On the left there is a sweeping, decorated loop, a generous oval, then in the centre three strong upright lines, and a curving decorated tail to the right. It’s an elegant, elaborate monogram cut from the top of an official document, and the whole design spells the title of the sultan whose authority it represents. The words are: ‘Suleiman, son of Selim Khan, ever victorious’. This simple Arabic phrase, elaborated into an emblem made out of lavish and opulent materials, speaks clearly of great wealth; it is no surprise that this ever-victorious sultan, the contemporary of Henry VIII and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, was later called by Europeans Suleiman the Magnificent.

Suleiman inherited an already expanding empire when he came to power in 1520. He went on to consolidate and extend his territory with almost unstoppable energy. Within a few years his armies had shattered the kingdom of Hungary, taken the Greek island of Rhodes, secured Tunis and fought the Portuguese for control of the Red Sea. Italy was now in the front-line. Suleiman seemed to envisage a restoration of the Roman Empire under Muslim rule – the dream of recovering an ancient Roman glory, which fired the Renaissance in western Europe, was also a spur to the greatest Ottoman achievements. The two hostile worlds shared the same impossible dream. When a Venetian ambassador expressed the hope of one day welcoming the sultan as a visitor to his city, Suleiman replied, ‘Certainly, but after I have captured Rome.’ He never did capture Rome, but today he is considered the greatest of all the Ottoman emperors.